The Battle of the River Raisin (18-23 January 1813), also known as the Battle of Frenchtown or the River Raisin Massacre, was a significant engagement in the War of 1812. It saw the defeat of a US army at Frenchtown (modern-day Monroe, Michigan) along the River Raisin, and the subsequent massacre of some of the surrendered US soldiers.

Background

On 16 August 1812, less than two months after the initial declaration of war, the United States suffered a humiliating defeat when the strategic outpost of Fort Detroit fell. Brigadier General William Hull, in command of the fort and its 2,500 defenders, had been terrified by the Native American warriors marching alongside the British troops; convinced that the Native warriors would massacre his men if the fort fell to an assault, Hull decided to surrender without a fight. While this may have saved the lives of his men, Hull's surrender cost the US control of the Michigan Territory, as British Lt. Colonel Henry Procter could now use Detroit as a base from which to expand his influence in the region. Even worse from a US perspective, the Siege of Detroit had encouraged more Native American nations to side with the British, hoping to recover the lands they had lost to the US in the Treaty of Greenville (1795). The recapture of Detroit was therefore a high priority for President James Madison and his administration, who entrusted the task to Major General William Henry Harrison, the popular hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe.

Harrison was placed in command of the reconstituted Army of the Northwest, which was largely made up of volunteers from the frontier state of Kentucky. These frontiersmen were despised by the British, who regarded them as half-wild 'savages' who lived on the fringes of civilization. "The Kentucky men are wretches," wrote one British officer, "suborned by the Government and capable of the greatest villainies… [they are] the most barbarous, illiterate beings in America" (Taylor, 208). Rowdy, resourceful, and quarrelsome, the Kentuckians were known to be clean shots and dirty fighters – in a Kentucky scrap, biting, scratching, and gouging were all considered fair play. They were hated and feared by the local Native Americans, who called them 'Big Knives' in reference to the long scalping knives the Kentuckians often wore on their belts. Decades of bad blood existed between the northwestern Native Americans and the Kentucky frontiersmen, with each group harboring painful memories of raids, killings, and mutilations committed by the other.

After taking command on 2 October 1812, Harrison decided to split his army into two columns. The leftmost column, under his second-in-command Brigadier General James Winchester, would push north along the Maumee River, while Harrison led the righthand column himself, advancing along the Upper Sandusky. The plan was for each column to reconvene at the Maumee Rapids near Lake Erie, to prepare for the final push to Fort Detroit. The going, however, was rough. Hindered by bad weather, low on supplies, and faced with the ever-present threat of a Native American ambush, each column made painfully slow progress. The situation worsened in late November when winter rapidly set in; one soldier, Kentucky rifleman William Atherton, would bleakly write that there was nothing "but hunger and cold and nakedness staring us in the face" (quoted in Berton, 291).

Harrison's column lost many horses to exhaustion in the effort to pull their cannons to the Upper Sandusky, forcing him to abandon several wagons loaded with precious supplies. At the same time, Winchester's column, which had barely begun its crawl up the Maumee, was forced to wait near Fort Defiance for fresh supplies. Poor sanitation and drainage in Winchester's camp soon led the men to be ravaged by disease; hundreds fell sick, with several men dying each day. "Our sufferings at this place have been greater than if we had been in a severe battle," wrote one soldier, "more than one hundred lives…lost owing to our bad accommodations! The sufferings of about three hundred sick at a time, who are exposed to the cold ground and deprived of every nourishment are sufficient proofs of our wretched condition!" (quoted in Berton, 292).

First Battle: 18 January

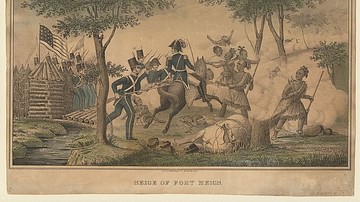

As Harrison's divided army crept toward Michigan, British Lt. Colonel Henry Procter prepared to meet the invasion. He sent out parties of troops to burn the lands around Detroit and to arrest any Michigan settlers liable to aid the Americans. On 14 January, Canadian Major Ebenezer Reynolds arrived at the small settlement of Frenchtown, on the River Raisin, with two companies of Essex militia and a band of 200 Potawatomi warriors; his orders were to destroy the village, take its supplies, and carry off the town's French-speaking population to Canada. As Reynolds and his men moved into Frenchtown to begin this process, several of the town's residents escaped and made their way to the US camp at the Maumee Rapids. Their pleas for help were echoed enthusiastically by Winchester's soldiers, who still hungered for battle and urged their commander to act. Though Winchester had been ordered by Harrison to stay put, he, too, sensed an easy victory and, after a brief war council on 17 January, decided to march to Frenchtown's rescue.

Winchester immediately dispatched Lt. Colonel William Lewis to march to Frenchtown with 550 men, supported by a second force of 100 Kentuckians under Lt. Colonel John Allen. At 3 p.m. on 18 January 1813, the Kentuckians crossed the frozen River Raisin and formed up a quarter mile outside Frenchtown, where they came under fire from the lone British howitzer in the village. The Americans advanced "under an incessant shower of bullets" but nevertheless managed to push the Canadian militia from the cluster of houses where they had gathered to make their stand. The fighting lasted until dusk, with the Americans not stopping until they had pushed the Canadians and Potawatomi two miles from the village. While it had only been a skirmish, the Americans reveled in their victory, feeling as though they had saved Frenchtown and its people from destruction; Colonel Lewis, in his report back to Winchester, proudly wrote that his men had "supported the double character of Americans and Kentuckians" (quoted in Berton, 301).

Upon learning of the victory, Winchester packed up camp and moved the rest of his army to join the triumphant troops at Frenchtown. Only a few hours later, General Harrison arrived at the Maumee Rapids with the first elements of his own column. Even though Winchester had disobeyed his orders, Harrison was delighted with the news of the victory; to reinforce Winchester's position, he sent four companies of regulars to Frenchtown as well as Captain Nathaniel Hart, who carried fresh orders for Winchester to hold his ground. When the reinforcements arrived, they found that Winchester had hardly bothered to fortify his new position. The general, having established his quarters in a comfortable log home a mile away from the rest of his troops, had failed to post pickets, consolidate his troops, or strengthen the shoddy palisade wall that guarded the town. The soldiers had also grown complacent; for the first time in months, they had access to fresh food and warm beds, and after their small battlefield success, they felt themselves invincible. Reports that a large British and Native American force was gathering for a counterattack were ignored, and all talks of moving camp to a more defensible position were postponed.

Second Battle: 22 January

On 19 January, the British and Canadian soldiers at Amherstburg – on the Canadian side of the Detroit River – were celebrating the birthday of Queen Charlotte when the festivities were interrupted by news of the battle at Frenchtown. Colonel Procter, acting with uncharacteristic swiftness, gathered a force of 567 British regulars and Canadian militiamen, as well as nearly 800 Native American warriors. In the absence of the Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh, who was off south trying to entice more Indigenous nations into joining his confederacy, Britain's Native American allies were led by the Wyandot chieftains Roundhead and Walk-in-the-Water. Many of the Native Americans had been forced from their homes by Harrison's army during its advance toward the Maumee Rapids, leaving them eager for revenge. Procter led this force into Michigan, arriving on the banks of the River Raisin outside Frenchtown in the predawn hours of 22 January 1813.

Most of the Kentuckian troops had been sleeping during Procter's silent approach and were awoken, in the words of one soldier, by the "thundering of cannon and roar of small arms, and the more terrific yelling of savages" (quoted in Taylor, 211). The disoriented and startled Kentuckians stumbled from their quarters and took a hasty defensive position on the left part of town, while the US regulars formed up on the right side. The regulars, most of whom were raw recruits, received the brunt of the British attack; their line was shredded by canister shot fired from Procter's six 3-pounder cannons, while their flanks were attacked by the Canadian militia and Roundhead's Native Americans. After only 20 minutes, the regulars broke and ran; the Native American warriors pursued, tomahawking and scalping any soldier who fell behind. General Winchester, having galloped the mile between his quarters and the battlefield, tried to rally the troops on the banks of the Raisin but failed to contain them, the panicked men scrambling across the frozen river.

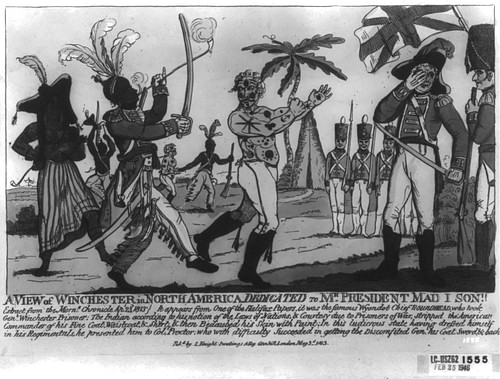

Winchester tried and failed to rally the regulars two more times before finally being surrounded by Roundhead's warriors. 147 US soldiers immediately threw down their weapons and surrendered. Others dispersed and ran into the woods, where they were soon hunted down. Colonel John Allen, having been wounded in the thigh, managed to limp two miles before two Potawatomi warriors caught up with him; he was shot dead and scalped. Winchester himself was taken alive. The Native Americans stripped him of his uniform and hauled him, shivering, to Colonel Procter, who demanded he order his men to lay down their arms. Winchester responded that, since he was now a prisoner, he was no longer in command; however, after Procter warned that he may not be able to restrain his Native American allies from indulging in slaughter, Winchester promised to recommend the rest of his troops to surrender.

While the US regulars had fled the battlefield, the Kentucky volunteers on the left flank fought on. Led by Major George Madison – a future governor of Kentucky – they held their ground around a clump of buildings. From these windows, the Kentucky marksmen inflicted heavy casualties; particularly, they targeted the British artillery crews, ultimately killing so many gunners as to effectively neutralize the enemy cannons. Although they were running low on ammunition, the Kentuckians were eager to keep fighting – and were therefore dismayed when they saw Procter approach under a white flag of truce, the captured Winchester beside him. Major Madison, horrified to see that his commander had already surrendered, refused to do the same without a guarantee that his men would not be harmed by the Native Americans. Procter was incensed by Madison's insolence, shouting, "Sir, do you mean to dictate for me?" Eventually, Procter agreed – though he did not put it in writing – and promised that no harm would come to the Kentuckians. Reluctantly, the frontiersmen laid down their arms, and the battle was over. It was an appalling defeat for the Americans who lost 397 killed, 80 wounded, and over 500 captured, while the British, Canadians, and Native Americans lost 24 killed and 158 wounded.

Massacre: 23 January

Despite his victory, Procter knew he could not linger in Frenchtown for long. Harrison was still at the Maumee Rapids with a large force and would soon be looking to seek revenge. Procter, therefore, decided to return to Amherstburg as soon as possible. He loaded his own wounded onto sleds but was unable to find enough space to accommodate the 80 Americans too wounded to walk. Promising that he would send more sleds to pick them up in the morning, Procter marched out of Frenchtown with his soldiers and his able-bodied prisoners on the evening of the 22nd, leaving behind a handful of Canadian militiamen to guard the wounded prisoners. Around 200 Native American warriors also remained behind to plunder the town. Their presence unnerved the Canadian militiamen, who slipped out of Frenchtown as darkness fell, whispering to the wounded Americans that "we are afraid of them ourselves" (quoted in Taylor, 212).

This left the wounded Kentuckians at the mercy of the Native Americans. Late at night, a Native American chief entered one of the two houses in which the prisoners were kept. Fluent in English, he spent two hours conversing with the wounded. But as he turned to go, he said something that chilled one of the prisoners, William Atherton, to the bone: "I am afraid that some of the mischievous boys will do some mischief before morning" (quoted in Berton, 314). Sure enough, before the sun had fully risen, several Native Americans entered the houses, robbing the wounded of their personal possessions including blankets and clothing. Afterwards, they set fire to the two houses with many of the wounded still inside; one horrified British eyewitness would later recall the "fierce glare of the flames, the crashing of the roofs, the sacrificing of the dying wretches enveloped in fire, and the savage triumphant yelling" (quoted in Taylor, 212). Any wounded man who managed to escape the burning wreckage was tomahawked and scalped.

Around 50 of the wounded Kentuckians died in the fire. The other 30 were marched off by the Native Americans, who meant to either ransom them off or to adopt them into their tribes – the latter was the custom for some Native American nations to replace those who had died in battle. Those Kentuckians who were too injured to keep up were killed. Captain Nathaniel Hart, brother-in-law of Kentucky War Hawk politician Henry Clay, was pulled from his horse and tomahawked on the road from Frenchtown. Another man, Private Charles Searls, was killed when his native captor flew into a rage at the mention of the name of William Henry Harrison. Although some of the captives, like young Atherton, would survive, the path the Native Americans took was soon marked by corpses. Hogs wasted no time feasting on the bodies; eyewitnesses would later recall the pigs running around with "skulls, arms, legs, and other parts of the human system in their mouths" (quoted in Taylor, 212). The meal apparently had an adverse effect on the hogs, who "appeared to be rendered mad by so profuse a diet of Christian flesh" (ibid).

Aftermath

The Battle of the River Raisin was the third military catastrophe suffered by the United States since the declaration of war only half a year before – the others being the Siege of Detroit (15-16 August) and the Battle of Queenston Heights (13 October). Another army had been lost, another general captured, and another opportunity to turn the tide of the war had been squandered. Colonel Procter was promoted to major general, and many of his comrades toasted yet another British victory. But as soon as word of the massacre reached Amherstburg, some of the British were less keen to celebrate; as one military surgeon put it, "Be assured we have not heard the last of this shameful transaction" (ibid). Indeed, Congress wasted no time propagandizing the River Raisin as a dreadful massacre, branding it as a war crime perpetrated by the British and their Native American allies. "Remember the Raisin!" became a rallying cry at recruitment drives across the country, as US citizens rushed to avenge their fallen countrymen. This new wave of anti-British, anti-Native American fervor would help propel the US to victories later that year, such as at the Battle of the Thames (5 October 1813).