The National Museum Zurich recently opened a comprehensive and multi perspectival exhibition on Switzerland’s colonial past: Colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements. Based on the latest, original research and drawing on biographies, as well as using objects, artworks, photographs, and written documents for illustrative purposes, Colonial explores the vicissitudes of Swiss colonial history from the 1500s up to the present era. In this interview, James Blake Wiener speaks to co-curator Marina Amstad to learn more.

JBW: Marina Amstad, thanks so much for speaking with me. I suspect that many museum visitors – like potential readers of this interview – may find the concept of “Swiss colonialism” to be puzzling given that Switzerland is renowned for its policy of neutrality and has never had any colonies of its own.

What was it then, which provided the impetus for a show on Swiss colonial history?

MA: For a long time, Swiss history was seen only in terms of what happened on the territory of present-day Switzerland. Since the 16th century, however, Swiss society has become increasingly globally interconnected. There were numerous Swiss individuals who participated in the colonial system. On the one hand, the exhibition aims to show the areas of colonial activity in which the Swiss were involved. On the other hand, it shows that Swiss history is also global history.

JBW: Several Swiss companies and private individuals participated in the transatlantic slave trade and amassed fortunes from trading in colonial products and exploiting enslaved people.

How extensive was Swiss participation in the Triangular Trade (from the 16th to 19th century - a three-way trade system between Africa, Europe, and the Americas), and how did activities connected to the trade enrich Switzerland’s economy?

MA: Current research has identified more than 250 Swiss companies and private individuals who were involved in the trade and deportation of more than 172,000 enslaved people. Some made large profits, others losses. The Swiss economy profited in several ways: On the one hand, through the direct profits that flowed into Switzerland, but also through the cheap raw materials from the colonies, such as cotton for the textile industry.

However, the question of whether Switzerland (as a state) also became rich as a result of its colonial connections is difficult to answer on the basis of current research. Individual companies and families undoubtedly benefited from colonialism, while the majority of the Swiss population still lived a poor and underprivileged life around 1900. It is important to point out that there is still a research gap (partly because certain archives in Switzerland are still inaccessible to researchers).

JBW: While many have an idealized picture of Switzerland as a bastion of neutrality, the martial valour and cunning of Swiss mercenary soldiers are as storied as they are important in Swiss history.

What can you tell us about those Swiss who served as mercenaries in European armies abroad? How are their actions presented within Colonial?

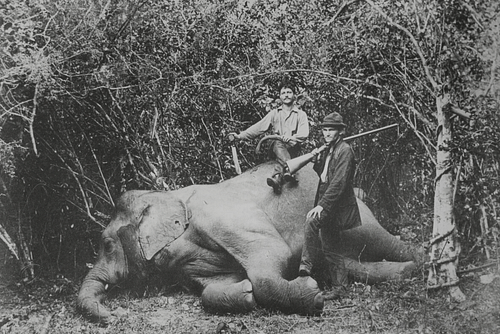

MA: For a long time, Swiss mercenaries have been remembered in a very positive light, ignoring the violence they both committed and experienced. Swiss mercenaries served in European colonial armies from the end of the 16th century, taking part in violent campaigns of conquest and the maintenance of colonial order. For example, the exhibition presents Hans Christoffel, a mercenary from Graubünden who served in the Royal Dutch Indian Army from 1886 to 1910. He was known for his authoritarian military style and his unscrupulous behaviour, including several massacres of indigenous people, for example on the island of Flores in present-day Indonesia. In a film, the descendants of the survivors of these massacres explain how they remember the mercenaries and the excesses of violence.

JBW: A sizable number of Swiss men and women traveled the world as missionaries, and an entire section of the exhibition is dedicated to their activities and religious zeal.

What is their significance in Swiss colonial history? How did they shape colonial ventures and settlements in Asia, Africa, and Latin America?

MA: Missionaries worked with local authorities to establish hospitals and schools. Although they were sometimes agents of social change, their relationships were often characterised by a paternalistic self-image. Above all, we show how the missionaries shaped the image of the colonies and the colonised, especially the image of "inferior" cultures, in Switzerland.

JBW: Can you tell us about how scientists at the universities of Zurich and Geneva formulated race theories to legitimize colonial systems in the late-nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries?

MA: Around 1900, the universities of Zurich and Geneva became international centres for so-called 'racial anthropology'. Alleged 'racial anthropologists' measured the skulls of people from all over the world and classified them into 'races'. The method of the 'Zurich School' in particular became the internationally accepted standard from the 1920s onwards. These analyses were also used to protect an allegedly endangered 'white race'. So-called ‘Race theory' and eugenics were still practised in Switzerland in isolated cases until the 1960s. Today, thanks in part to genetic research, the idea of a 'human race' has been officially discredited.

JBW: By drawing parallels to contemporary issues, Colonial also ponders the open question of what this colonial heritage means for present-day Switzerland.

With that in mind, how should visitors grapple with the complex nature of Switzerland’s colonial entanglements? Moreover, what would you like visitors to walk away with following a tour of Colonial?

MA: With all these historical issues, we have always been concerned with the question: what does this have to do with us as a society? It is not our responsibility what people did before us. But it is our responsibility how we deal with this colonial legacy. Because colonialism has left its mark, in our language, in our history books, in our administrations, in our minds. Colonial mindsets still have an impact today, and in order to recognise and break them, we need to understand where they come from. Visitors should realise that Switzerland, as part of the global world, also has to deal with the consequences of colonialism.

JBW: On behalf of World History Encyclopedia and its readers, I thank you very much for sharing your time and expertise with us.

MA: Thanks very much for your interest in our exhibition.

Colonial – Switzerland’s Global Entanglements is on show at the National Museum Zurich through January 19, 2025. The exhibition continues in an adapted form, from 27 March to 11 October 2026, at the Château de Prangins.

Marina Amstad is a historian and exhibition curator at the Swiss National Museum. She studied history and Slavonic studies in Basel, specialising in modern and contemporary history. Since 2016, she has been working on various exhibitions at the National Museum Zurich. She is co-curator of the exhibition Colonial—Switzerland’s Global Entanglements.