The Battle of York (27 April 1813) was a major battle in the War of 1812. It saw an American army, under Brigadier General Zebulon Pike, defeat a British, Canadian, and Ojibwe force to seize York (present-day Toronto), the capital of Upper Canada. It was the first significant US victory to be won on land during the war.

Background

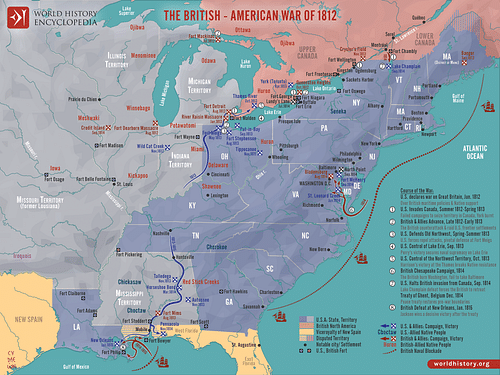

The six months that followed the United States' declaration of war against the United Kingdom had not gone well for the Americans. An attempted invasion of Canada had culminated in disaster at the Siege of Detroit (15-16 August 1812), where US Brigadier General William Hull was forced to surrender both his army and Fort Detroit itself, thereby giving the British control of the Michigan Territory. Two months later, another US invasion was decisively defeated at the Battle of Queenston Heights (13 October), where nearly 1,000 US troops were taken prisoner. To make matters worse, a third American force was pulverized at the Battle of the River Raisin (18-23 January 1813) in Michigan, a bloody episode that concluded with the massacre of wounded US troops by Britain's Native American allies. These three defeats made it abundantly clear that a successful invasion of Canada would take a lot more than the "mere matter of marching" that had been anticipated by former president Thomas Jefferson.

Hoping for a reversal of the United States' dismal military fortunes, President James Madison appointed a new secretary of war, John Armstrong, Jr., in January 1813. Having studied the defeats of the previous year, Armstrong realized that control of the Great Lakes – specifically Lake Ontario – was essential for any attack on Canada to succeed. Working with Major General Henry Dearborn, the US commander of the Niagara frontier, and Commodore Isaac Chauncey of the US Navy, Armstrong planned for a squadron of ships to be built at Sacket's Harbor, on the New York side of Lake Ontario. Once completed, this squadron could ferry Dearborn's troops across the lake to strike at Kingston, the location of the major British dockyard on Lake Ontario; if captured, Kingston would give the Americans full control of the lake. Unfortunately for Armstrong, however, the British had the same idea and ordered the construction of two new sloops-of-war on Lake Ontario. The 20-gun HMS Wolfe was being built at Kingston while its sister ship, HMS Sir Isaac Brock – named after the British war hero recently slain at Queenston Heights – was under construction at York. Throughout the early winter months of 1813, therefore, the sounds of construction rang out across the lake as each side raced to get its ships in the water before the other.

But as winter gave way to spring and the campaign season drew nearer, Dearborn and Chauncey started to second-guess their target. They believed Kingston was too well-guarded; according to some reports, the town was protected by 8,000 men, including 3,000 British regulars. This estimate was, in truth, a wild exaggeration – the British had only 900 regulars and a few hundred Canadian militia at Kingston – but Dearborn and Chauncey had no way of knowing this. Working under the assumption that Kingston was indeed too strong for an attack, they shifted the focus of their expedition to York (present-day Toronto). Though it was less strategically valuable than Kingston, York was the capital of Upper Canada, meaning its capture could at least help restore the United States' honor after the humiliations of 1812; the possibility of capturing the still-unfinished Sir Isaac Brock was a bonus as well. The two commanders succeeded in convincing Armstrong to sign off on the changed plan. Then, with Chauncey's ships afloat and Dearborn's soldiers gathered at Sacket's Harbor, the Americans had only to wait for the ice to finish thawing before they could learn whether their luck would change.

Preparations

By early April 1813, the British had begun to suspect that the Americans were planning an attack on York. Major General Roger Hale Sheaffe, the lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, had been in York on official business when he learned that the town was the Americans' intended target, leading him to postpone his return to Fort George in order to shore up local defenses. Unfortunately for him, he had little resources with which to do so. At his immediate disposal, Sheaffe had only 300 British regulars, 300 Canadian militia, and around 100 Ojibwe warriors; any attempt to pull in reinforcements from another front would probably come too late. The town itself was defended by a fortress, aptly named Fort York, to the west, and a blockhouse on the Don River to the east. The British had three batteries at Fort York while two more 12-pounder cannons were at the nearby Government House Battery. As he worked to prepare these defenses, Sheaffe ordered all important legislative papers and military documents to be buried in the woods behind York, to keep them out of American hands if the town should fall.

On 18 April, the ice on Sacket's Harbor finally thawed enough to free up the American ships, and they immediately prepared to set sail. Commodore Chauncey's new squadron included a corvette – the flagship USS Madison – as well as a brig and twelve schooners. Around 1,700 US soldiers were loaded onto these ships, many of them regulars under the command of 34-year-old Brigadier General Zebulon Pike. A career soldier and explorer, Pike felt that he had been underappreciated for much of his military tenure and was eager to taste military glory. Thus far, his only claim to fame was an exploratory expedition – the 1806 Pike Expedition – into the Great Plains and Rocky Mountains, the success of which was ultimately overshadowed by the concurrent Lewis and Clark Expedition. Pike had not even been able to successfully summit the mountain that now bears his name, Pike's Peak. He, therefore, felt as though he had much to prove and was determined to either win the coming battle or die a hero's death. General Dearborn also set sail with the fleet aboard USS Madison, but owing to a lingering illness, he opted to remain on the ship during the battle, entrusting command of the ground forces to General Pike.

The American squadron set sail on 25 April and was spotted off the Scarborough bluffs by British sentries late the following evening. Early on the morning of 27 April, the defenders and civilian population of York watched with anxiety as the American ships rounded Gibraltar Point at the western end of the Toronto Islands and entered the harbor. Sheaffe knew that he could not allow the Americans to establish a beachhead and, as soon as the ships came into view, he ordered Major James Givins to contest the landing with a group of Ojibwe warriors; at this point in the war, the US soldiers' fear of the Natives was well-known, and Sheaffe hoped that their presence would demoralize the attackers. Sheaffe soon decided to send a company of British grenadiers, under Captain Neal McNeale, in support of Givins' Native Americans, and positioned his militia, under adjutant general Aeneas Shaw, to guard the British right flank and watch for any attempted American flanking maneuvers.

The Battle

As Sheaffe rushed to get his troops into position, the first wave of American boats landed on the Canadian shore, about four miles (6 km) west of town. Out jumped Captain Benjamin Forsyth and his 300 green-jacketed riflemen, who wasted no time skirmishing with the handful of Ojibwe warriors sent to guard the shoreline. Forsyth's riflemen were supported by the American schooners, which fired rounds of grapeshot from the harbor. Under this hail of fire, the Ojibwes quickly fell back, withdrawing into the safety of the woods. Forsyth, therefore, was able to secure a beachhead and allowed the second wave of American boats, led by General Pike himself, to land. After wading ashore, Pike ordered his men to fix bayonets, just in time for McNeale's grenadier company to emerge from the trees. The grenadiers immediately found themselves caught in a crossfire between Forsyth's riflemen and the American schooners in the harbor. McNeale fell dead, as did many of his comrades, leaving the survivors to pull back beyond the tree line.

They were pursued by Forsyth's riflemen, who were in their element in the dense woodland; taking cover behind trees, the US riflemen inflicted terror on the British regulars, whose bright red coats made them easy targets. The grenadiers were pushed back further as the chaos mounted; according to legend, two grenadiers fell through the ice of a pond and drowned amidst the confusion, leading the pond to afterward be known as 'Grenadier Pond'. In the meantime, Pike organized his regulars into columns and led them into the woods, along the main road that hugged the shoreline. As the soldiers marched, their fifes and drums blaring the tune Yankee Doodle, they could hear the cheers of the American sailors in the harbor, urging them onward. The British, meanwhile, tried to make a stand around the Western Battery, a battery located a mile away from the fort. But, as Pike's men approached, one of the British gunners accidentally dropped a match into the battery's magazine, causing a massive explosion that killed 20 men and sent the survivors running.

Before long, the British had withdrawn to Fort York itself, which was now under bombardment from the American ships in the harbor. General Sheaffe, riding out to survey the position, realized that the battle was as good as lost. Understanding that well-trained British regulars were a precious resource on the Canadian frontier, he resolved to extricate as many of them as possible, even if he had to give up York. He barked a flurry of orders, telling his men to burn anything they could not take with them, including the unfinished warship Sir Isaac Brock which was soon consumed by flames. Once this had been done, Sheaffe led the regulars over the Don River, burning the bridge behind them, and set out eastward toward Kingston. Since most of the Ojibwe warriors had already fled the battle, the hapless Canadian militia were left to fend for themselves as Pike's soldiers drew ever nearer.

By 1 p.m., the Americans had come within 400 yards (365 m) of Fort York. Pike, elated that his long-sought victory was finally at hand, ordered his men to halt as they waited for the American gunners to bring up two cannons captured from the British batteries. Pike sat down on a tree stump and had only just begun to interrogate a captured Canadian militia sergeant when a thunderous roar shook the earth. Before leaving Fort York, the British had rigged the fort's magazine – which contained 300 barrels of gunpowder – to blow up. The massive explosion sent debris, including large chunks of stone, beams, and metal, flying off in every direction in a 500-yard (457 m) radius. 222 Americans were killed or wounded in the explosion, including Pike, whose ribs were crushed by a boulder. Realizing his wound was mortal, Pike lived long enough to see the American flag raised above the ruined fort, before being borne back to the deck of USS Madison, where he died, his head resting on the captured British flag. With this dramatic climax, the battle came to an end. The Americans lost 265 casualties – most of these sustained in the explosion – while the British suffered 475 losses.

Burning of York

Abandoned by Sheaffe and the British regulars, the leaders of the Canadian militia were eager to strike a peace deal with the Americans. It was left to Colonel William Chewett, the 60-year-old commander of the militia, to negotiate such a deal along with his second-in-command, Major William Allan. But the Americans, shaken by the explosion, were in no mood for clemency. The negotiations stalled, and nothing was finalized until the next morning, when General Dearborn rowed out to shore. No sooner had he set foot on land than he was accosted by Reverend John Strachan, one of York's leading citizens who had taken over the Canadian peace delegation. Sensing an opportunity to increase his influence in Upper Canada, Strachan was determined to be the one to strike the peace deal and relentlessly hounded Dearborn to agree to the articles of capitulation that had been drawn up the previous evening. Dearborn was soon worn down by Strachan's forcefulness and agreed to ratify the articles, which included paroling the Canadian militiamen – that is, allowing them to return home on the condition that they swear not to take up arms against the Americans – and promising to respect all private property in York.

But before Dearborn could ratify the terms of surrender, he was informed that the British had burned the Sir Isaac Brock, the capture of which had been one of his primary objectives. Feeling slighted, he delayed signing the terms, during which time US soldiers and sailors began to plunder the town. Under the pretext of looking for hidden weapons, the soldiers looted houses belonging to Canadian civilians, carrying off anything of value; the local sheriff would later report that, "those who abandoned their houses found nothing but the bare walls at their return" (Taylor, 215). Forsyth's riflemen were noted to be some of the most egregious offenders, as they were often seen walking the town streets with handkerchiefs full of stolen valuables. Eventually, a group of American soldiers broke into the Government House, the residence of the lieutenant governor, where they were enraged to find a scalp hanging in the chamber. Though this 'scalp' may just have been the Speaker's wig, its discovery provoked the Americans into setting fire to the Government House and the nearby Legislative Assembly. US soldiers also broke into the Printing Office and destroyed the printing press there.

Dearborn had not intended for his men to pillage York and was embarrassed by their behavior, though he did not do much to leash them. He finally ratified the articles of capitulation, and, by 30 April, the worst of the looting had stopped. Aware of the rising tensions between his men and the Canadians, Dearborn was eager to get out of York; indeed, he had never intended to permanently occupy the town, but rather to strip it of its military supplies and leave. On 2 May, the Americans loaded the captured munitions and cannons onboard Chauncey's ships for transport and marched out of York on 8 May. As soon as Dearborn left, Reverend Strachan and the other leading citizens retook control of York and wasted no time cracking down on those Canadians who had aided the Americans during their two-week occupation. Those who had so much as spoken favorably of the Americans were indicted and were forever after branded as traitors.

Aftermath

The Battle of York had been the first major US victory of the war on land, but it was not as complete as it could have been. By burning the uncompleted HMS Sir Isaac Brock, the British denied the Americans one of the main prizes they sought, and by blowing up the gunpowder in Fort York, they had soured the Americans' victory by inflicting mass casualties, including the promising General Pike. Worst of all, Sheaffe had been allowed to escape with most of the British regulars, a fault that Secretary of War Armstrong blamed on the sluggish Dearborn; within a few months, Dearborn would be relieved of command. Sheaffe, likewise, was blamed for the loss by Reverend Strachan and the other prominent York citizens, who successfully petitioned Canada's Governor General, Sir George Prevost, for his removal. Finally, the British would not soon forget the burning and pillaging of York and would use this as their justification when, a year later, they burned the American capital of Washington, D.C.