The Battle of Fort George (27 May 1813) was an important battle in the War of 1812. It saw the United States launch a successful amphibious assault to capture Fort George, the main British outpost on the Niagara frontier. The Americans, however, failed to capitalize on their victory, and would ultimately abandon the fort seven months later.

Background: Burning of York

Ever since the opening of hostilities in June 1812, the capture of Canada had been the primary objective of the US government. But several factors – including the unpreparedness of the US military and the incompetence of its general officers – led the first two attempted invasions to end in humiliating failures. By early 1813, with support for the war wavering at home, it was clear that a new approach would have to be taken if the US hoped to wrench Canada from British control. Such an approach was offered by John Armstrong, Jr., the new US secretary of war, who believed that no invasion of Canada would succeed without prior control of the Great Lakes, specifically Lakes Erie and Ontario. If the Americans could achieve naval domination on these lakes, they could strike at vulnerable military outposts and towns along the lakeshore, including York (present-day Toronto), Kingston, and Fort George. In this manner, the Americans could conquer Canada piecemeal.

With this goal in mind, Armstrong ordered a squadron of ships constructed at Sacket's Harbor, on the New York side of Lake Ontario. Placed under the command of Commodore Isaac Chauncey, this flotilla consisted of a corvette – the flagship USS Madison – a brig, and twelve schooners. Once completed, the ships were loaded with 1,700 US soldiers under Major General Henry Dearborn before setting sail for York, the capital of Upper Canada. On 27 April 1813, with Chauncey's ships anchored in Toronto Bay, the US soldiers rowed ashore, establishing a beachhead 4 miles (6 km) to the west of town. Led by the daring Brigadier General Zebulon Pike (Dearborn was supposedly too ill to lead the attack himself), the American soldiers advanced toward York overland as the schooners provided covering fire from the harbor. The British regulars and Canadian militia were outnumbered and slowly fell back. Eventually, the British were ordered to retreat, but not before blowing up the gunpowder magazine in Fort York. The explosion devastated the approaching US troops, as pieces of rock, metal, and other debris rained down upon them. The blast caused over 200 American casualties, including General Pike, who was killed after his ribs were crushed by a falling boulder.

Although their victory was dampened by the explosion, the Americans succeeded in occupying York, marking their first significant land victory of the war. Despite promises made by General Dearborn that private property would be respected, the US soldiers indulged in two days of looting; not only did they carry off valuables found in private homes but they also burned several official buildings including the Government House and the Legislative Assembly (the British would cite these burnings as justification for the burning of Washington, D.C., the following year). Dearborn lingered in York for only two weeks, long enough to load the captured military supplies onto the ships, before marching back to the American lines on 8 May. The Battle of York, though it had not been as complete a victory as Secretary of War Armstrong would have liked, still proved the merits of his plan. Having ravished York, the Americans next turned their sights toward Fort George, the main British military outpost on Lake Ontario. But this time, the Americans did not intend on simply leaving after capturing their objective; this time, they meant to begin their invasion of Canada in earnest.

Preparations

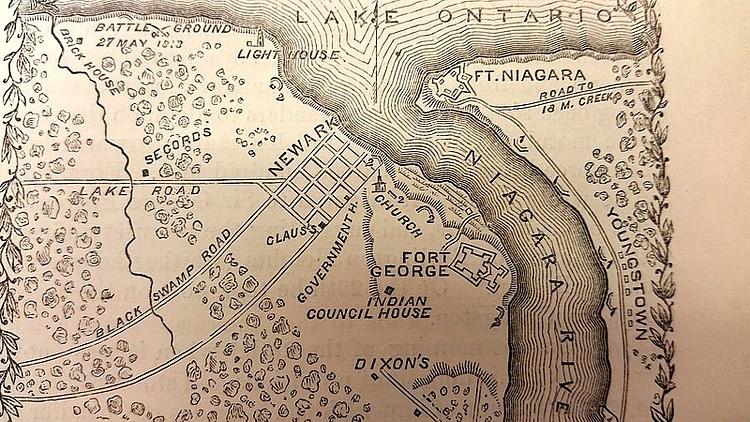

Located on the Canadian side of the Niagara River, in the present-day town of Niagara-on-the-Lake, Fort George had become the center of British military activity along the Niagara frontier. It was built in 1796 as a replacement for Fort Niagara, which Britain had been obliged to give to the United States in accordance with the Jay Treaty. It was protected by six earthen bastions connected by a palisade wall and consisted of five log blockhouses, as well as officers' quarters, barracks, a kitchen, and a gunpowder magazine. In May 1813, the fort was under the command of British Brigadier General John Vincent, who had about 1,000 regular soldiers spread across the Niagara Peninsula: these included soldiers of the King's Regiment (the 8th Regiment), the 49th Regiment, and companies from the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles and Glengarry Light Infantry. This force was supplemented by around 300 Canadian militia and around 100 Native American warriors, most of them Mohawks.

The Americans, meanwhile, had apportioned a force of 4,500 regulars to take part in the coming attack. The first wave was to be led by 26-year-old Colonel Winfield Scott, a six-foot-five (195 cm), 230-pound (104 kg) Virginian, who had recently been returned to the Americans in a prisoner exchange following his capture at the Battle of Queenston Heights (13 October 1812). Scott's initial assault would be followed by two more waves of US troops, led by Brigadier General John Parker Boyd and Brigadier General William H. Winder, respectively. Prior to the war, Boyd had been a soldier of fortune fighting in India, while Winder was a Baltimore lawyer who achieved his rank through political connections; neither man was much respected by professional US soldiers like Scott. Also present with the American force was Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry, who was temporarily serving on USS Madison as one of Commodore Chauncey's senior officers; in only a few months' time, Perry would win one of the most famous naval actions of the war at the Battle of Lake Erie (10 September 1813). With these men assembled at Sacket's Harbor, the Americans were ready to attack.

The Landing

On the morning of 25 May 1813, the peaceful stillness of dawn was shattered by the roar of artillery. Chauncey's twelve schooners had begun to open fire on Fort George to soften its defenses in preparation for the infantry landing. From across the river, the American guns at Fort Niagara were also firing; to maximize damage, the gunners at Niagara heated their cannonballs in the furnace before firing them, hoping to spark fires within the wooden British fort. Indeed, several of Fort George's log buildings were soon engulfed in flames, forcing the women and children residing in the fort to seek cover within the earthen bastions or to flee altogether. Due to the location of the American guns, British General Vincent was convinced that the attack would come from across the Niagara River and therefore positioned his troops to brace for an assault from that direction.

However, the attack would not come from the river, but from Lake Ontario to the west. On the morning of 27 May, just as the early morning fog began to dissipate, General Vincent was shocked to see 16 American vessels sailing across the lake in a two-mile (3 km) arc. As the ships drew nearer, Vincent saw that they were accompanied by 134 bateaux and scows, loaded with US soldiers and artillery pieces. Presently, the American vessels opened fire, adding to the chorus of artillery fire that was still resounding off the Niagara River. A group of 50 Mohawk warriors, allied to the British, were watching the approach of the American ships from an overlook when they were spotted and struck by a hail of cannonballs. Two of the Mohawks were killed, and several more were wounded; shaken by the experience, the surviving Mohawks fled the battle, depriving the British of the Native American support on which they so often relied. The fire from the American schooners was directed by the energetic Oliver Hazard Perry himself, who rowed in a small boat from ship to ship to tell each one where to drop anchor and aim its fire.

In the meantime, the first wave of American boats –containing around 800 men and led by Colonel Scott – neared the Canadian shore. A proud and disciplined soldier, Scott was determined to redeem his reputation after his capture at Queenston at all costs and wasted no time leaping into the water as soon as it became shallow enough for him to do so. The beach was guarded by British regulars of the Glengarry Light Infantry, who rushed into the water to meet the disembarking Americans head-on, bayonets fixed. After a fierce hand-to-hand struggle, the Glengarry men were pushed back with heavy casualties. The troops of the Royal Newfoundland Fencibles rushed to their aid but were shredded by rounds of grapeshot fired from the American schooners, causing them to fall back as well.

Scott led his men up the beach and crested a 12-foot (3.6 m) clay bank. Here, they clashed again with the British soldiers, who had rallied and been reinforced by several companies of the King's Regiment and of the Canadian militia. Now it was the Americans' turn to be driven back, and Scott, trying to rally his troops, lost his footing and slipped off the bank. His men, believing him to have been shot, were on the point of running when Scott stood up and, without hesitation, began rushing back up the bank. With a cheer, his men followed, and, with help from Boyd's wave of troops who had just landed, they drove the British off the bank. The British regrouped in a ravine where they made their final stand, trading fire with the Americans at point-blank range for 15 minutes. But as more and more Americans landed, the British position proved untenable, and they were forced to retreat once more. Every British field officer and most of the junior officers had been killed or wounded in the exchange.

Capture of the Fort

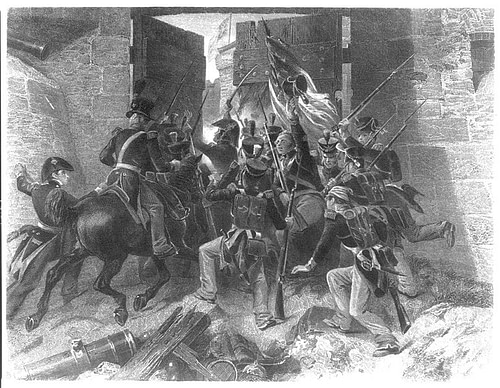

By now, Boyd had nearly finished landing all his 1,500 men while Winder's brigade was still in the process of disembarking. British General Vincent, concerned that his men would soon be surrounded by the larger US force, opted to evacuate Fort George rather than try to withstand a siege. He ordered the fort's garrison to spike the cannons and blow up the powder magazines before falling back to Queenston, a few miles to the south. The magazine exploded just as Scott approached the fort with his men, the blast forceful enough to knock him off his horse and break his collarbone. The persistent colonel was soon back on his feet and, despite his injury, led his men into the fort. The Americans chopped down the flagpole, with Scott taking the captured Union Jack as a souvenir.

Although he had taken the fort, Scott was not yet satisfied. He had seen the last of Vincent's troops retreating into the woods and was determined to go after them. But much to his dismay, Scott was ordered to stay put by Major General Morgan Lewis, second-in-command of Dearborn's army. Lewis, the kind of politician-soldier Scott hated, worried that the day's victory could still be ruined by a careless error; paranoid that the woods were full of hostile Native Americans, he forbade Scott from entering them in pursuit of the British. Scott protested, saying "I have the enemy within my power…in seventy minutes, I shall bag their whole force" (Berton, 441). But it was no use. General Boyd, echoing Lewis' sentiments, directly ordered Scott to remain at Fort George. Thus, the proud Virginian colonel was forced to stand down as the British troops slipped away into the woods, out of his grasp. The Battle of Fort George was over; the Americans had lost approximately 200 casualties, while the British and Canadians lost around 200 killed or wounded, and another 270 captured.

Aftermath

As they had done at York, the American troops spent the immediate aftermath of the battle looting the nearby town of Newark, a plunder so complete that many residents would later return to find only "empty rooms and bare walls" in their homes (Taylor, 218). General Lewis, embarrassed at his inability to restrain his troops, implausibly blamed the plunder on the retreating British troops. But despite this unruly behavior, the Americans had won perhaps their greatest victory of the war so far; they had managed to capture Fort George while inflicting a greater number of casualties than they sustained. Moreover, the fall of Fort George forced Vincent to consolidate his troops, leading him to evacuate the British garrisons from other defensive points like Fort Erie. The stage, it seemed, was finally set for a major US invasion of Canada.

But the Americans, commanded by the sluggish and perpetually ill General Dearborn, failed to exploit their victory. In the following month, they would be checked by the British and Canadians at the Battle of Stoney Creek (6 June) and the Battle of Beaver Dams (24 June), while American naval power was briefly hindered by a British raid on Sacket's Harbor. Following this debacle, the Americans stayed cooped up in Fort George, effectively under siege by a much smaller number of British and Canadian troops. In the coming months, the American garrison would be ravaged by disease, thinning their numbers and worsening morale. This stalemate would finally end in December 1813, when the Americans abandoned Fort George, leaving it to be recaptured by the British. Had the Americans followed up on their victory immediately after taking the fort – or had Scott been allowed to pursue Vincent's retreating army – the Battle of Fort George could have been a major turning point and may have led to the conquest of Upper Canada. Instead, it became just another fleeting victory in a war that was seeming increasingly pointless.