A group of German generals attempted to assassinate the leader of Nazi Germany Adolf Hitler (1889-1945) using a bomb on 20 July 1944 but failed. The conspirators were against Hitler's conduct of the Second World War (1939-45) and Nazism in general and wanted an honourable surrender while there was still a chance of saving Germany from destruction.

Hitler was injured by the bomb left by Claus von Stauffenberg (1907-1944) but lived to instigate brutal reprisals on anyone remotely connected to the plot. The conspirators, called the Schwarze Kapelle ('Black Orchestra') by the Gestapo, the Nazi secret police, included senior generals, diplomats, and aristocrats who had hoped to stage a coup d'etat following Hitler's death. The conspirators were hunted down as several thousand were tortured and brutally executed.

Hitler as War Leader

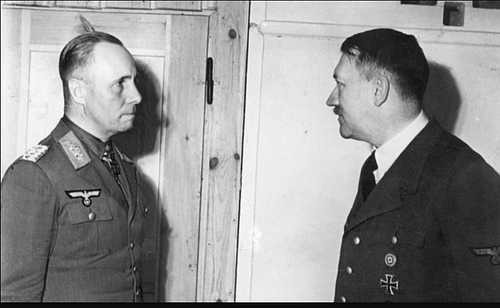

Adolf Hitler was the absolute dictator of Nazi Germany and the supreme commander of all Germany's armed forces. In addition, all armed forces personnel had to swear allegiance to Hitler personally. Germany had started WWII with a string of victories, which included the Fall of France in 1940, but from 1942, the Allies began to gain the upper hand. As a war leader, Hitler proved incapable of appreciating the strategic consequences of his decisions. Operation Barbarossa, the attack on the USSR, ended in failure for many reasons, but Hitler's persistence in overriding his generals, such as his decision to halt the advance on Moscow and insistence that the army at the battle of Stalingrad fight to the death, did not help. Distrustful of experts, Hitler believed his generals were too pessimistic, and so he made himself the Feldherr or commander of the German armies in the field. It was also in 1942 that the North Africa Campaign seriously deteriorated following defeat at the Second Battle of El Alamein (Oct-Nov 1942). Nevertheless, Hitler continued his military meddling by dismissing generals on a whim. Even if he had not been strategically inept, the sheer volume of work he gave himself by refusing to delegate meant that Hitler's decisions were not based on detailed analysis of any given military situation.

The D-Day Normandy landings of June 1944 finally opened a second front, and Germany found itself squeezed between the two armies of the Allies. It seemed to many of Germany's top generals that the war was already lost and it would be better to surrender with honour now before Germany itself was invaded. This was not an option for Hitler, and so a group of generals decided to take matters into their own hands.

The Conspirators

The conspirators were a mixed group of aristocrats, diplomats, and senior generals, all united in their belief that to prolong the war would only cost many more lives and possibly the total destruction of Germany itself. Almost all of these men were devout Protestants, who abhorred Nazism. Many had been involved with the army plot to remove Hitler during the Czechoslovakian crisis of 1938, but when the Munich Agreement rewarded Hitler's bluff with the peaceful acquisition of the Czech Sudetenland, the generals backed down. Moves were made again to try and bypass Hitler and negotiate an end to the war four years later. Dietrich Bonhoeffer (1906-1945), a theologian, approached the Allies in Stockholm with a peace plan in May 1942. The conspirators were naive in their terms, considering, for example, that the union with Austria (Anschluss) should be allowed to stand and Germany should keep such territories as parts of Poland. The Allies, already suspicious that such a move might be a Nazi trick, rejected Bonhoeffer's terms. The conspirators, nevertheless, continued to entertain ideas that Germany could keep some of its ill-gotten territorial acquisitions by presenting itself as a bulwark against communism.

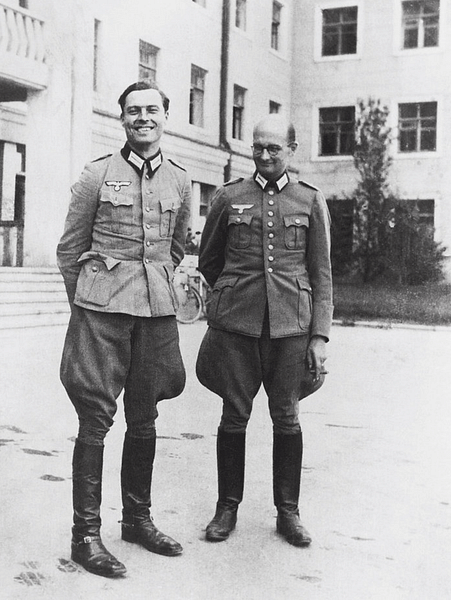

The 1944 plotters were led by Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg in terms of carrying out the assassination plan, but behind him was a large group of much more senior figures. The choice to replace Hitler after the assassination was General Ludwig Beck (1880-1944), an anti-Nazi who had resigned in 1938 when Hitler revealed his plans to occupy Czechoslovakia. Another key figure was Ulrich von Hassell (1881-1944), the German ambassador to Italy between 1932 and 1938. Both Hassell and the ex-mayor of Leipzig Carl Goerdeler (1884-1945), who was lined up to become chancellor after Hitler's death, were instrumental in gathering in new recruits to the plot, travelling widely across Europe to meet potential sympathisers in person and explain their ambitious plans for a coup d'etat and negotiated surrender. Field marshal Erwin von Witzleben (1881-1944) was a long-time anti-Nazi plotter, and he was to take over as head of the German armed forces upon Hitler's demise.

Other leading names in favour of the plot included Admiral Wilhelm Canaris (1887-1945) and Major-General Hans Oster (1888-1945), the head and deputy respectively of the Abwehr, the German military intelligence organization. Oster, amongst other subversive activities against the Nazi regime, helped Jewish people escape the Holocaust, and so he was suspended from his post in April 1943. General Henning von Tresckow (1901-1944) was in on the plan as he had been plotting to blow up Hitler ever since 1939.

There were many potential sympathisers to the cause, although some were against the idea of killing Hitler and wanted merely to arrest him. The conspirators believed this was not enough since other Nazis would surely attempt to free the Führer. Others were sympathetic but did not want to get involved themselves, figures such as Helmuth von Moltke (1907-1945), a descendant of the Prussian field marshal of the same name. Moltke was right to be cautious since even his tentative association with the plotters was discovered by the Gestapo, and he was hanged for it. Finally, many serving generals rebuffed the approaches of the conspirators outright, men like the field marshals Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953) and Erich von Manstein (1887-1973), who reminded them that, as army officers, they had all sworn an oath of allegiance to Hitler

The Plan: Valkyrie

Stauffenberg was the catalyst for all of these noble sentiments to finally evolve into some sort of practical plan. The count was a striking figure following injuries sustained in the aftermath of the Battle of Kasserine Pass (1943) in the North Africa Campaign: he had lost his right hand and forearm, two fingers of his left hand, and wore a patch over his blinded left eye. The young officer became a favourite of Hitler's, as the armaments minister Albert Speer (1905-1981) notes: "Hitler himself would occasionally urge me to work closely and confidentially with Stauffenberg…In spite of his war injuries…Stauffenberg had preserved a youthful charm; he was curiously poetic…" (Speer, 509).

Stauffenberg's plan was to kill Hitler using a bomb he himself took to the target area while elsewhere the SS (the Nazi's rival organization to the army) and Gestapo would be neutralised by the regular army and a new government established in Berlin. Timing was to be everything since the coup must accomplish its aims before senior Nazis could launch a response. The operation was given a code name: Valkyrie, the spear-carrying female warrior of Norse mythology who decides the fate of warriors in battle. If the army heads heard this codeword signalled from Berlin, then they would know what to do. To cover their tracks, the conspirators gave Valkyrie a cloak of respectability by linking it to standard emergency measures if ever a situation arose that threatened the state.

The crux of the whole plot was getting an explosive device near Hitler, already a highly suspicious, even paranoid dictator. Stauffenberg had two advantages besides his personal courage. First, his significant injuries meant that he was unlikely to be searched by Hitler's bodyguards. Second, he had direct access to Hitler in his role as chief of staff of the Replacement Army. Stauffenberg selected the place to carry out the assassination: Hitler's isolated command headquarters deep in the woods of East Prussia, known as the Wolf's Lair (Wolfsschanze).

Stauffenberg filled a briefcase with one kilogram (2.2 lbs) of plastic explosive and fitted to it a pencil timer that would set off the bomb ten minutes after activation. The bomb was, appropriately enough, a captured British-made device. Stauffenberg had to abort his plan three times, but he was fourth time lucky on 20 July. This day witnessed a full solar eclipse, but if it was an omen of things to come, who was about to eclipse whom? Hitler was conducting his usual conference that morning in a room with a single large table, for maps to be spread out on and consulted. The conference was held in a hut because the usual location, an underground room, was being refurbished (although the historian W. L. Shirer maintains that this bunker room was only used during air raids). Stauffenberg was called into the room early by Hitler and so did not have time to add a second kilogram of explosive to the case, as he had intended. Stauffenberg set the timer and placed his deadly briefcase under the centre of the conference table, where Hitler was pacing up and down. Stauffenberg then removed himself with the excuse he had to make a telephone call. In a quirk of fate, one man in the packed room, Colonel Brandt, stubbed his boot against the case and so moved it further down the table.

Stauffenberg waited anxiously outside for the minutes to tick down; it was about a quarter to one in the afternoon. A terrific explosion ripped the quiet forest air. Flames shot up and several men were blown right through the hut's windows. Hitler was surely dead. As planned, another conspirator at the scene, General Erich von Fellgiebel (1886-1944), moved to cut all lines of communication to and from the Wolf's Lair. Stauffenberg left the compound and flew to Berlin in a waiting plane to oversee the next stage of Valkyrie.

The Coup Fails

The hut had been blown apart, but out of the debris now staggered several survivors, including Hitler with his hair on fire and his trousers blown to tatters. The dictator suffered a temporary paralysis in his right arm and damaged hearing, a permanent consequence of which was a lack of balance for the rest of his life. The fact the bomb had gone off in a hut and not underground, as well as being placed under a heavy oak table, greatly lessened its impact. Nevertheless, four of Hitler's staff were killed outright or later died from their injuries: Brandt, General Schmundt, General Korten, and a stenographer. Several others were seriously wounded.

Valkyrie had failed in its main objective, but other things quickly started to go wrong. Fellgiebel did not manage to cut off all communications from the Wolf's Lair, a crucial mistake that allowed Hitler's supporters to know that the Führer was still alive. Nor were communications in Berlin or the radio stations taken over. In the capital, the conspirators were divided over how to proceed since Fellgiebel's message had been garbled, and they were not certain the bomb had killed Hitler. A meeting in the war ministry was joined by Stauffenberg, and finally, orders were sent out to other cities that Valkyrie must go ahead. Without the definite news that Hitler was dead, though, nobody seriously carried out the plan except in Paris where senior SS members were briefly arrested by General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel (1886-1945). When it came to the crunch, the plotters had not gained as widespread support for their coup as they thought they had.

In Berlin, the Grossdeutschland guard battalion, under the command of conspirator Major Otto-Ernst Remer (1912-1997), was meant to mobilise and give the coup some military might in the capital while the Replacement Army mobilised elsewhere. Remer was ordered by the plotters to arrest the minister of propaganda Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945), but Goebbels persuaded Remer of the folly of his actions now Hitler was known to have survived. Goebbels insisted the doubtful Remer speak to the Führer on the telephone, a conversation which ended with Remer's immediate promotion to the rank of colonel. In these brief few minutes, the coup had failed.

Remer, made by Hitler responsible for all military matters in Berlin, returned to the war ministry and arrested those conspirators still there. Some wily plotters, like General Friedrich Fromm (1888-1945), tried to bluff it out and claim they had nothing to do with the coup. Fromm, to make his claim more convincing, even ordered the execution of several fellow conspirators. Meanwhile, on the evening of the 20th, Goebbels announced on the radio that an attempt on Hitler's life had been made, but the Führer was already back at work, and arrests had been made of the traitors involved. Hitler himself addressed the nation via radio broadcast at 1 a.m. on 21 July. Hitler assured the German people he was fine and that the conspirators would pay for their criminal act.

The public was shocked at these events since, as General Heinz Guderian (1888-1954) noted, "the great proportion of the German people still believed in Adolf Hitler and would have been convinced that with his death the assassin had removed the only man who might still have been able to bring the war to a favourable conclusion" (Shirer, 1082).

Hitler's Revenge

Hitler's miraculous survival convinced him more than ever that providence was on his side. It also convinced him that treachery in the army was the real reason for Germany's defeats in the war. Hitler was determined to gain revenge on the plotters. Stauffenberg, under Fromm's orders, was shot by a firing squad on the night of the assassination attempt. Moments before he died, the count shouted "Long Live Free Germany" (Boatner, 536). The others were more methodically dealt with as Heinrich Himmler (1900-1945), head of the SS, swung into action with gusto.

The Gestapo called the group they held responsible for the plot the Schwarze Kapelle ('Black Orchestra'). Hitler insisted anyone connected to the plot be arrested, interrogated, and, in many cases, executed. The plotters were certainly let down by their obvious lack of internal security. Many of the Black Orchestra had unwisely used insecure telephone lines, recorded conversations in diaries, and kept records of names and addresses relevant to the group, even a list of who was to take what positions in the future government. Most were rounded up easily enough, especially since the Gestapo had infiltrated the various conspirator groups long before Valkyrie was attempted. Even the children of conspirators were arrested. Over the next year, the Gestapo and the SS went on to arrest thousands more people, both to ensure anyone with even a remote link to the plot paid the price for their treachery and to get rid of old enemies at the same time.

General Beck attempted suicide but failed, necessitating an associate shoot him fatally in the neck. General Stülpnagel also tried and failed to commit suicide; he was later hanged. Tresckow took no chances and blew himself up using a hand grenade. Those plotters who were arrested were often tortured for information or simply for the pleasure of their sadistic captors. There were show trials at the so-called People's Court, an institution presided over by the uncompromising Roland Friesler (1893-1945). During their brief trials, the accused were not permitted to give any dignified defence or dress appropriately – Witzleben even had his false teeth confiscated.

Witzleben and eight more key plotters were hanged in August 1944. Goerdeler was hanged in February 1945. Bonhoeffer, Canaris (who was first brutally beaten), and Oster were all executed the next April. One SS officer later reported that Canaris' death had taken 30 minutes. General von Fellgiebel was executed in September after enduring three weeks of torture. Hassell was hanged the same month. Even General Fromm, who had turned coat at the very end, was arrested, tortured, and executed. Most hangings were not actual hangings in the strictest sense, rather, the victims were suspended from meat hooks in the ceiling using piano wire. Hitler insisted the gruesome deaths of the conspirators be filmed and sound recorded so that he could later watch the results of his terrible vengeance. The films were so gruesome Hitler had to abandon his idea of releasing them to the public.

The fallout of Valkyrie continued for many months. One of the high-profile victims was Germany's most celebrated commander Field Marshal Erwin Rommel (1891-1944), who had only remote connections to the plot but was implicated when mentioned by a delirious Stülpnagel. Rommel was obliged to take his own life in order to protect his family and avoid a reputation-damaging show trial, which would have, in any case, found him guilty and sentenced him to death.

Hitler never trusted any of his generals ever again and made sure he always had an SS bodyguard around him. The arrests, trials, executions, and deportations to concentration camps related to the 1944 plot were still being carried out as the Allies closed in on Berlin in 1945. There was some poetic justice in that the People's Court was hit by a bomb during a US air raid in February, which caused a beam to fall and kill Judge Friesler. By April 1945, Hitler could no longer avoid his fate, and he committed suicide as the USSR's Red Army approached his Berlin bunker.