The Siege of Fort Meigs (28 April to 9 May 1813) was a major engagement on the northwestern frontier of the War of 1812. It saw a US army under Major General William Henry Harrison, holed up in the hastily built Fort Meigs, withstand a siege by British and Native American forces despite heavy casualties.

Background

On 16 August 1812, the US outpost of Fort Detroit surrendered to a British and Native American force after a brief and nearly bloodless siege. At a stroke, the British had seized control of the entire Michigan Territory, which they could now use as a staging ground for an invasion of western US states like Ohio or Kentucky. Even worse from a US perspective, the Siege of Detroit had emboldened several previously neutral Native American nations to side with the British and begin to attack US outposts and settlements. Many of these northwestern Native Americans had been driven from their lands by the US after the Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794) and were eager to reclaim what they had lost; indeed, the British promised to help the Native Americans set up their own, independent confederacy on lands west of the Ohio River. Such a confederacy would serve British interests by acting as a buffer state between Canada and the US.

The US was anxious to prevent a hostile, British-backed Native American confederacy from arising on its western frontier and knew that it had to balance the scales by retaking Detroit. Such an important task was entrusted to William Henry Harrison, the popular former governor of the Indiana Territory and the hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe (7 November 1811). Harrison was given the rank of major general and placed in command of the newly formed Army of the Northwest, comprised mainly of raw volunteers from Kentucky and Ohio serving six-month enlistments. In early October, this army set out from Fort Defiance in Ohio, but bad weather and poor logistics slowed its advance to a crawl. Before long, winter was setting in, and Harrison begrudgingly concluded that he would be unable to assault Detroit before spring. He ordered the advance column of his army, under Brigadier General James Winchester, to continue marching to the Maumee Rapids (near present-day Toledo, Ohio) where they would begin setting up camp for the winter.

Winchester's men arrived at the Maumee Rapids in mid-January 1813. Having been on the march for weeks by this point, most of these men were cold, wet, and hungry; many of their enlistments were about to expire, and they longed to fight a battle before being sent home if only to make their long miles of miserable marching worth it. They would soon get an opportunity, as word reached their camp that a detachment of Canadian militia had occupied Frenchtown, a small community on the River Raisin in Michigan, and was harassing its inhabitants. The Americans begged Winchester to let them march to Frenchtown's rescue. Winchester, enticed by the prospect of an easy victory, relented and sent several companies of Kentuckians into Michigan.

On 18 January, the Kentuckians easily routed the Canadians, causing an elated Winchester to move the rest of his column to Frenchtown as well. Once there, the inexperienced Americans grew complacent, neglecting to post adequate pickets or fortify their position. Therefore, the Americans were caught by surprise when a British and Native American force, under Sir Henry Procter, counterattacked just before dawn on 22 January. The Americans were defeated, and many were killed in the fighting. Of the survivors, those who could walk were taken across the Detroit River to Amherstburg as prisoners, while those too wounded to move were left behind in Frenchtown. That night, many of these wounded would be massacred by Potawatomi warriors allied with the British.

Building the Fort

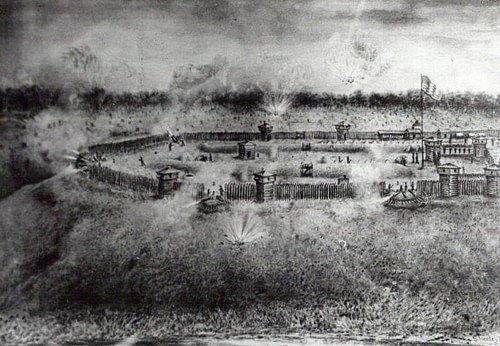

When Harrison learned of Winchester's defeat at the Battle of the River Raisin, he pulled the rest of his army back to a ridge 100 feet (30 m) above the Maumee River, near present-day Perrysburg, Ohio. On 1 February 1813, Harrison began construction of a fortified camp at this location named Fort Meigs in honor of Ohio Governor Return J. Meigs, Jr. The fort consisted of eight meager blockhouses enclosed by a palisade wall 15 feet (4.5 m) high. Work on the fort was slowed by bitter winter temperatures; during one particularly bad cold spell, a sentry froze to death while on guard duty, and men tore down sections of the wall to use the timber for firewood. At the same time, the enlistments of many of Harrison's militiamen began to expire, and he was forced to offer substantial bribes to each man who agreed to stay until reinforcements could arrive.

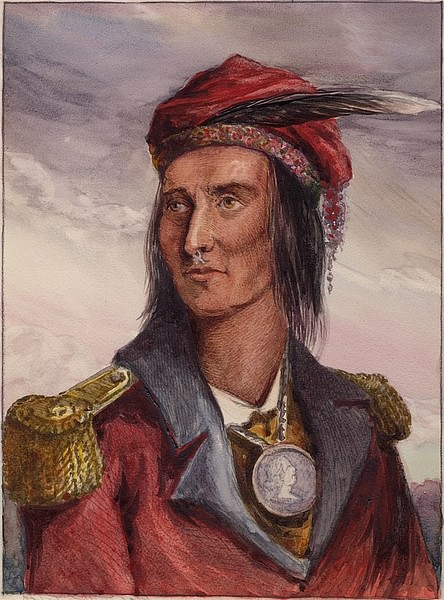

Harrison understood his position was precarious and, moreover, knew that it was only a matter of time before the British attacked him. He wrote to Governor Isaac Shelby of Kentucky to ask for more troops, emphasizing the urgency of the situation. Shelby responded swiftly, enacting a new law that allowed him to raise a force of 1,500 new volunteers. This force was placed under the command of militia general Green Clay, a cousin of the influential Speaker of the House Henry Clay, and was sent into the Maumee Valley to march to the aid of Fort Meigs. At the same time, the British began to stir; Henry Procter, promoted to major general after his victory at Frenchtown, had learned of the weak condition of Harrison's army and prepared to strike. By early April, he had mustered a force of 400 British regulars, 400 Canadian militia, and around 1,200 Native American warriors under the command of the great Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh. The British also had ten pieces of artillery, including two 24-pound cannons taken from Detroit, and two gunboats.

The Siege Begins

On 26 April 1813, Procter's force disembarked at the mouth of the Maumee River and made its way to the ruins of old Fort Miami where they set up camp. This was a significant site for the Native American warriors with the army, as it was near the spot where the Battle of Fallen Timbers had been fought 19 years earlier, a battle that had cost their people much. On 28 April, Tecumseh's Native Americans crossed the river and surrounded Fort Meigs, clearly itching to get revenge. The chieftain himself, who had faced off with Harrison before, sent a message to the fort in which he directly challenged the general:

I have with me 800 braves. You have an equal number in your hiding place. Come out with them and give me battle. You talked like a brave man when we met…and I respected you, but now you hide behind logs and earth like a groundhog. Give me your answer.

(Berton, 483)

Harrison refused to respond. By now, he was aware that General Clay's reinforcements were on their way and knew that his best bet was to hold out in the fort until their arrival. The British had begun to establish batteries on a ridge across the river from Fort Meigs, leading Harrison to order his men to dig a series of trenches in response. Aware of the need for secrecy, the Americans worked at night, digging by the light of the moon and stars. Just before dawn, they would move their tents over the trenches, thereby hiding their progress from prying eyes. Their progress was hindered by heavy and incessant rainfall on the nights of 28 and 29 April that turned the ground to mud and filled the trenches with water. Luckily for the Americans, the rain also slowed the British, who were frustrated in their attempts to finish setting up their batteries; in one instance, it took them six hours to drag one cannon across a single mile of muddy, rain-soaked ground. As each side struggled to prepare for the coming bombardment, the Native Americans kept a close eye on the fort; any US soldier who ventured outside the palisade walls was at risk of being picked off by the watchful warriors.

Finally, on 1 May, the British artillery was in position, and at 11 a.m., the guns opened fire. But no sooner had the first cannon gone off, than the row of American tents collapsed, revealing the completed trenches in which the US soldiers were sheltering. The many hours the Americans had spent digging paid off, as the British missiles went soaring harmlessly above their heads. The British would fire over 250 cannonballs over the next several hours, many of which become lodged in the mud around the American trenches. Harrison, knowing that the Americans could reuse the ammunition, offered a gill of whiskey to any man who retrieved a cannonball and brought it back to the magazine. This proved to be a great incentive; in the words of historian Pierre Berton, before the siege was over "more than one thousand gills [had] gone down the throats of the resourceful soldiers" (486). Moreover, during the entire cannonade, only one American was killed, and only a few more were wounded.

On 4 May, the third day of the bombardment, the British sent a messenger to Fort Meigs to request its surrender. But the Americans remembered that the surrendered US soldiers had been slaughtered after the Battle of the River Raisin, with many of them blaming British General Procter for allowing the massacre to happen. Harrison rejected the demand, stating:

Assure [General Procter] that he will never have this post surrendered to him upon any terms. Should it fall into his hands, it will be in a manner calculated to do him more honor, and to give him larger claims upon the gratitude of his government, than any capitulation could possibly do.

(Berton, 489)

Harrison, in other words, was saying that he was ready to fight to the last man. But as the British messenger departed, Harrison realized that his last stand might come sooner than he would have wished. His men were, after all, dangerously low on ammunition, food, and drinking water, and they would soon be too exhausted to resist a spirited British and Native American assault. He was, therefore, relieved when he learned around midnight that Clay's reinforcements were only a two-hour march away. Hoping that the sudden arrival of the fresh Kentucky volunteers could lend him the element of surprise, Harrison quickly scratched out a plan in a letter and sent an aide to deliver it to Clay with all speed. The plan called for part of Clay's force to storm the British batteries and spike the guns, while the rest attacked the Native Americans on the US side of the bank. This would free up Harrison's troops to rush out of the fort and join the attack, which he hoped would push the British back and end the siege.

Dudley's Massacre

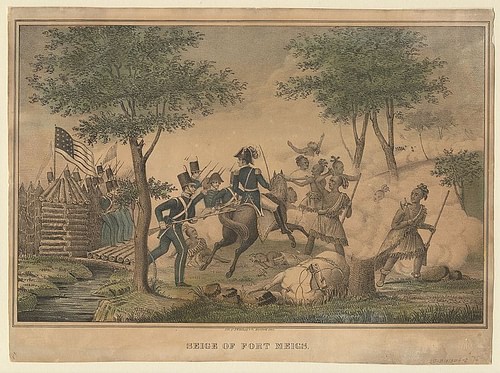

Clay, having received Harrison's orders, prepared to launch his attack. Early on the morning of 5 May, he sent a flotilla of flatbottom boats up the Maumee River, carrying around 800 men led by Lt. Colonel William Dudley. These men were tasked with spiking the British guns, while Clay himself led the rest of his troops to attack Tecumseh's warriors along the riverbank. Colonel Dudley, a man that Harrison would later describe as "weak and obstinate but brave" landed his men on the north bank of the river, as the sound of the British cannons echoed through the trees. The Kentuckians crept forward, silently moving through the woods, until they got to the British battery. Then, they charged forward with a fearsome yell, sending the terrified British gunners running without a fight. The Kentuckians did not even bother to wait for the spikes but shoved their ramrods into the cannons' powder holes, thereby neutralizing the battery.

At this point, Dudley's men should have fallen back to join the rest of Clay's brigade. But the Kentuckians, intoxicated by their easy victory, noticed some Native American warriors fleeing into the woods, and could not resist giving chase. Leaving a small group of men under Major James Shelby to guard the captured battery, Dudley led the rest of his troops into the woods in pursuit of the Native Americans. Little did the Kentuckians know that this was a trap. Lured deep into the trees, the Kentuckians were soon disorientated and lost; when Tecumseh's warriors leaped out at them from the brush, they stood little chance. Many of the Kentuckians – including Dudley himself – were killed and scalped, with only 150 survivors making it out of the woods and back to the fort. In the meantime, Shelby's paltry force was overwhelmed and defeated by British Major Adam Muir and three companies of British regulars. Although the rest of Clay's brigade had safely made it to Fort Meigs, most of Dudley's men had been annihilated, leading this incident to become known as ‘Dudley's Massacre'.

But for those Kentuckians who had been taken prisoner, the day's horrors were not yet over. They were taken back to the ruins of Fort Miami, where their Native American captors had put the naked, scalped corpses of their compatriots on hedgerows. Some of the Kentuckians were then forced to run past a line of Native Americans, who proceeded to beat the prisoners with clubs, rifle butts, and tomahawks. One Kentuckian prisoner would later recall how he became buried beneath the bodies of his friends but could still hear the "cracking of skulls around him" (Berton, 497). The massacre was put to an end by Tecumseh himself, who was enraged to find that it was taking place. The Shawnee chieftain confronted General Procter, demanding to know why he had not put a stop to the slaughter. When Procter claimed that he had tried but the Native Americans would not obey, Tecumseh had shouted, "Begone, you are unfit to command. Go and put on petticoats" (Berton, 498). Roughly 15 prisoners had been killed before Tecumseh's intervention.

End of Siege

In the aftermath of Dudley's massacre, the siege continued, as the British resumed their artillery bombardment and the Americans hunkered down in their trenches. But Procter soon found that his army was dissipating; most of his Native American warriors went home with their loot and prisoners, as was their custom after a battle, while his Canadian militiamen urged him to let them go home to tend to their farms. Realizing that the Americans in the fort would soon outnumber him, Procter knew there was little he could do but abandon the siege. On 7 May, he arranged for a prisoner exchange and, two days later, lifted the siege altogether. American casualties for the entire siege amounted to 986: 160 killed, 190 wounded, and roughly 630 taken prisoner. The British and their allies lost 121 killed, wounded, or missing. But despite these lopsided casualties, Harrison and his men had withstood the siege. Their pyrrhic victory at Fort Meigs meant that they would live to fight another day, which would eventually lead to one of the most decisive US victories of the war at the Battle of the Thames (5 October 1813).