Mediterranean trade increased exponentially at the turn of the first millennium. During Rome's zenith, goods of all sorts began to move in all directions. As a common traveler aboard merchant ships, Paul traveled within such a milieu. Tracing the water portion of his journeys in the New Testament can shed light on general trade patterns in the Mediterranean Sea areas.

Trade at the Turn of the Millennium

As the Roman Republic in the latter centuries of the last millennium BCE began to conquer the littoral nations around the Mediterranean – including those of Europe, Northwest Africa, and Anatolia, the Mediterranean Sea indeed became, to the Romans, Mare Nostrum, "our sea." Then, with Rome's takeover of Syria, Phoenicia, and Egypt, by the time of Paul the Apostle, Rome's encirclement of control was complete. Rome became the main market for agricultural, material, and refined goods that, as a result, moved largely from East to West. Then, as the extent of the Roman Empire grew, followed by the colonization and urbanization of its eastern provinces, the empire's eastern half began to develop a degree of commercial autonomy that created an interactive network of activity.

Around 200 BCE, goods from the East moved through Mesopotamia to the Levant and Anatolia by overland routes from India and by water up the Persian Gulf, which was then taken by camel to Seleucia, near modern-day Bagdad. Another route in the Eastern trade network of ancient Rome was goods sailing from the northwestern ports of India to Alexandria via the Red Sea. However, by the early Augustan period, with Rome's eventual control of Arabia and the Red Sea, there began a dramatic increase in Eastern items moving west to Rome, including silks, decorated cotton, shells, tortoiseshell, coral, ivory, nard, aloe, frankincense, myrrh, and spices like pepper, cinnamon and cassia.

Adding to Rome's consumption, with 300,000 veterans of the Roman army to find land for, Augustus (r. 27 BCE to 14 CE) established 75 colonies throughout the empire. According to Nigel Rodgers, "All these generally small settlements – usually a couple of thousand veterans, growing perhaps into a city of 10-15,000 – helped the urbanization and Romanization of the empire" (87). Additionally, as the eastern Roman provinces began to mirror Rome in structure and taste, demand for the same goods increased. Those goods would, therefore, begin to travel not just west to Rome but were manufactured and traded in all directions. It was this commercial environment in which the journeys of Paul the Apostle took place.

Eastern Goods Moving West to Anatolia

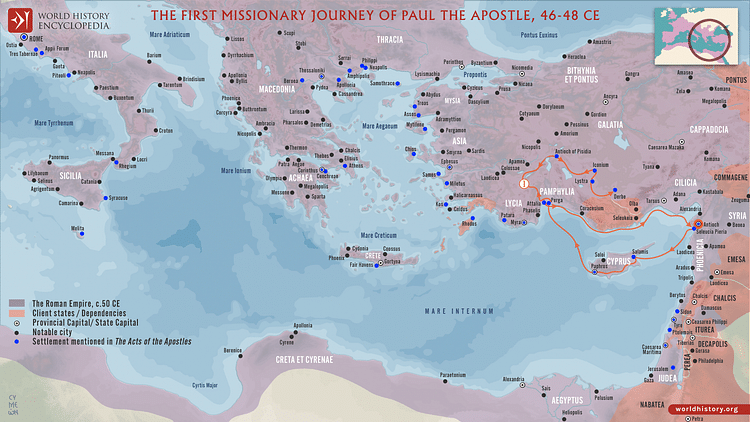

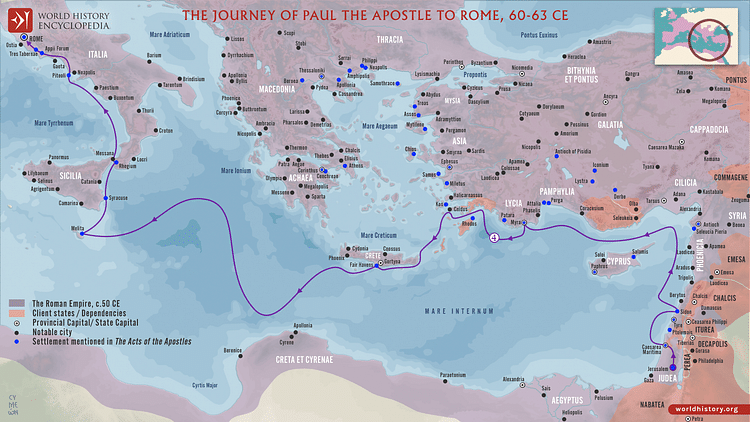

Of the estimated 16,000 km (10,000 mi) that Paul clocked during his travels, the sea portion of his first journey in Acts 13:1-13 consisted of two parts: the first from Antioch to Cyprus; then on to Perga in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey). Once rivaling Alexandria, Antioch benefited from its location at the western terminus of the Silk Road and its proximity to Anatolia, Greece, and Italy.

Annexed by Pompey the Great in 64 BCE, and made the Roman provincial capital of Syria, Antioch, as it lay on the Orontes River and at the edge of a large and fertile plain, communicated commercially with the harbor of Seleucia 24 km (15 mi) downstream on the Mediterranean. With an estimated population of 250,000, Antioch was one of the primary cities of the East, along with Alexandria and Constantinople. Besides being a major wine and olive oil producer and a center for the fulling of cloth products, the city likely acted as a distribution center for silk from China, lapis lazuli from Afghanistan, dye-works from the Levant, and weaved silk from Damascus.

Cyprus on the other hand, with a prominent location at the eastern end of the Mediterranean, was also known for its wine and olive oil production. A scenario for trade was likely a combination of Eastern goods loaded alongside refined and agricultural products accumulated at Antioch with a stop at Cyprus for partial distribution while its products would have been added for final distribution in Anatolia.

Goods Moving East From Greece

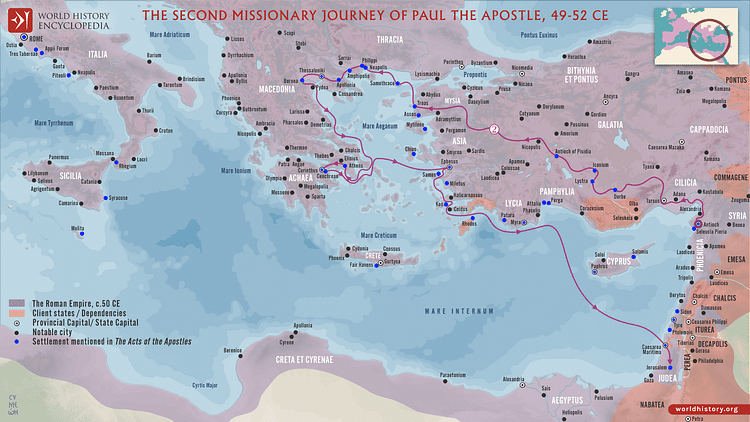

On Paul's second journey (Acts 15-18), after traveling throughout Anatolia and Greece, he leaves Corinth's port of Cenchreae in Greece for Ephesus and then goes on to Caesarea Maritima. One of the largest cities of Greece, Corinth was once a busy trading center. With land access to the Peloponnese, it dominated trade in the Saronic Gulf to the east and the Gulf of Corinth to the west. Through these waters, with access to the Adriatic and Aegean Seas, Corinth may have exported, to some degree, its own perfume and textile products. As to its bronze-making skills and exports:

Corinthian bronze was highly prized for its color, and the Corinthian metalworking industry was highly respected . . . Athenaeus (5.199e) refers to two famous Corinthian bowls with capacities of more than 360 liters each, with seated figures on the rim and relief figures on the neck and body.

(Mattusch, 433-34)

Pliny the Elder (23-79 CE) states Corinthian bronze, concerning its utility, was more valuable than silver and almost as valuable as gold, and was "the standard of monetary value." He further declares that it was so celebrated in antiquity there was a "mania" for possession of it and relates how Gegania, a wealthy lady, paid 50,000 sesterces for a Corinthian lamp-stand (34.1, 3, 6). Although "Bronzeworking and ironworking were carried out in the Forum Area at Corinth from the sixth century B.C. to the twelfth century A.D", only small finds of Corinthian bronze have been discovered thus far throughout the Greek mainland and Macedonia (Mattusch, 434). However, as bronze can be remolded and reused, the volume of finds may not represent full production.

Two other products from Corinth that were likely produced for wider export were stone and roof tiles. A facility known as the Tile Factory was found not far from the center of Corinth, and the significant use of Corinthian stone and roof tiles is evident in the construction of the 4th-century temples at Epidaurus and Delphi. Additionally, Corinthian pottery was a famous export with a significant range in the Mediterranean;

The overwhelming preponderance of Corinthian vases in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy up to the Straits of Messina demonstrates that a conscious effort was made to establish and maintain a market for Corinthian vases in these areas.

(Salmon, 140)

Though in lesser volume, Corinthian pottery has also been found on islands in the Aegean, at Delos in graves, and in the sanctuary of Hera; on the western coast of Asia Minor; and inland, such as at Sardis. Corinthian pottery has also been found in Greek colonies on the Black Sea, on non-Greek sites on the southern coast of Asia Minor, and in the Levant.

The two main ports on the Isthmus of Corinth were Lechaeum and Cenchreae. Lechaeum was the port for Corinthian goods going west, and Cenchreae (the port Paul left from) for those headed east. However, despite its significant commercial past, after the enervating Corinth-Corcyra, Peloponnesian, and Corinthian wars, Corinth was finally destroyed by the Romans in 146 BCE. But, with its rebuilding by Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE), it likely resumed the production of some of the products it was familiar with and exported them to places like Ephesus and Caesarea.

Successive Servicing & Metals From Anatolia

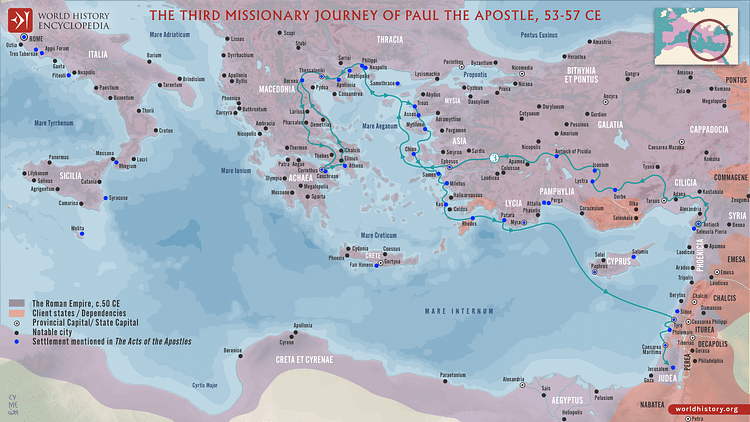

As part of his water itinerary on his third journey in Acts 18-21, as he did in getting to Greece on his second trip, Paul would return to Anatolia using the Troas/Phillipi route. The junket between Troas and Philippi was a common one. Troas, a port city on the eastern side of the Aegean, was known for its location, which connected Asia with Europe. Phillipi, on the Aegean's west side, was a Roman colony whose station on the via Egnatia, a major Roman road, connected it to the Dardanelles and the Adriatic. Their proximity across from each other on the upper Aegean made seagoing activity between the two a natural development.

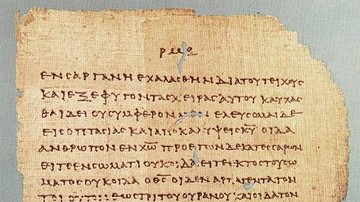

After Troas, Paul's water portion of his journey back home begins with a trip going southeast from Assos to Mitylene, then on to Miletus. Mitylene was the main port city for the island of Lesbos, while Miletus was an important Ionian port serving Ephesus. Trade between the two districts probably involved heavier loads, as the trip from Mitylene to Miletus took three days involving two stops. "And sailing from there, we arrived the following day opposite Chios; and the next day we crossed over to Samos; and the day following, we came to Miletus." (Acts 20:14-15)

From Miletus, they sail to the Lycian port of Patara, with stops at Cos and Rhodes, presumably to unload or add on cargo. That the trip from Miletus to Patara, a commercial center for Anatolia, was a longer one with two stops indicates Miletus' significance to maritime trade in the region. At Patara, they board another ship for the longer non-stop route south to Tyre, where the ship unloads its cargo. Though Paul's destination was Caesarea, his stops at Tyre first, then Ptolemais, reveal his itinerary was determined by the scheduling of vessels from one port to the next. Sidon, Tyre, Ptolemais, and Caesarea were cities close in proximity on the Phoenician seaboard. Thus, while Paul's trip along the Anatolian coast reflects a surprising level of regional and interregional activity, his stops along the Phoenician coast reveal similar successive servicing.

Finally, concerning the load from Patara, evidence for the traditional production of agricultural goods and animal husbandry in Anatolia reaches back to the first centuries of the 2nd millennium BCE during the Kārum period. The other main resource from the Anatolian plateau was metals. With evidence of metal production going back to the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, "Anatolia is a land blessed with abundant natural resources, including a wealth of mineral deposits and abundant forests, the two elements necessary for a major metal industry" (Muhly, 858-59). Furthermore, while the production of Anatolian copper, gold, silver, iron, and lead was documented by Pliny and Strabo (c. 63 BCE to 24 CE), modern surveys confirm that Anatolia was, from 3000 BCE to the Ottoman period, a significant producer of copper and possibly tin, essential ingredients in the production of bronze.

Consequently, as Anatolia provided for its own agricultural needs and received luxury goods from Antioch, with the southeastern Mediterranean's agrarian appetite satisfied thanks to Alexandria, the goods loaded at Patara for Tyre and Caesarea were likely metal ingots. As it relates to Tyre, besides the production of its famous purple-dyed cloth, according to the biblical account in 1 Kings 7:13-45, in mid-900 BCE, Tyre provided finished bronze products such as pillars, capitals, figures, shovels, stands, basins, and bowls for Solomon's temple. Moreover, as Tyre was known by other ancient writers for its finished metal products, and "Caesarea had a license from Rome to mint bronze coins which were used as a means of exchange in the area's rapidly developing economy," such material demand for this kind of production again suggests a metal load from Anatolia (Bull, 27).

Caesarea, Sidon, & Grain to Rome

While the water portion of Paul's second and third journeys ended at Caesarea and his last journey started from there – of the commercial centers and ports mentioned in Paul's travels, perhaps the most significant for Rome was Caesarea. That Flavius Josephus (36-100) called it "a very great city in Judea" and the Roman emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79) and his son Titus (r. 79-81) stationed their troops at Caesarea during the Great Jewish Revolt of 66 CE also reflects the city's status (Wars, 3.9.1). Likewise, tracing and fleshing out Paul's final journey as a prisoner of Rome in Acts 27-28 may further clarify Caesarea Maritima's role in the Mediterranean trade.

After his arrest in Jerusalem and imprisonment at Caesarea, Paul boarded a ship from Adramyttium on the northwest coast of Anatolia and headed for Myra on Anatolia's southern coast. After leaving Caesarea, the Adramyttium ship stopped at Sidon, a short journey north. Once providing ships and goods for Persia, Sidon was also an important manufacturer of luxury goods such as glass, dyes, and embroidered garments. Furthermore, as Caesarea was built over the ruins of Straton's Tower, which was named after King Straton I (r. 365-352 BCE) of Sidon, Strabo reports it had its own "station for vessels" (16.2.27). With its location in the midst of shipping and trade routes, north of Alexandria and 120 km between Gaza and Sidon, Straton's Tower reflects Sidon's scale of commercial influence. After leaving Caesarea, the ship stopped at Sidon a short journey north on its way to Myra, a grain storage center. This indicates that it likely added Sidon's finished products to the merchandise it was already carrying, possibly ivory or tortoiseshell from Africa, papyrus from Egypt, or spices and incense from the East.

At Myra, Paul and his fellow prisoners would be transferred to an Alexandrian ship, loaded with grain, headed for Rome. Since Myra shared the same Aegean coastline south of the great cities of Ephesus and Smyrna, these cities would likely have shared in the products from Caesarea and Sidon. That Paul disembarked this vessel at Myra for the Alexandrian one indicates the Adramyttium ship did not load grain for Rome since that is where Paul was headed and would have stayed on board. Neither did it need to load grain to take back to Caesarea since Caesarea was already adequately supplied, but it may have, with an empty hold, trekked back to Caesarea to start the same or a similar circuit again.

Paul's boarding at Myra onto an Alexandrian ship full of grain and prisoners headed for Italy may indicate that Myra was part of its itinerary, which was first to unload some of its cargo at Myra to make room for the prisoners it would transport to Rome. The Alexandrian ships were known as the giant freighters of their day. One such ship, the Isis, as described by Lucian, had a length of 55 meters (180 ft) and a beam of 14 meters (45 ft); with a cargo hold depth of 13.5 meters (44 ft), it could carry 1200 tons of product. Likewise, reflecting their wide range of use, after the wreck of the Alexandrian ship from Myra on the island of Malta, Paul's company would board another Alexandrian vessel that had wintered at Malta, which, with the advent of spring, would head for Rome.

Conclusion

As Paul traveled aboard cargo ships that performed trade transactions throughout the Mediterranean, his journeys provide a glimpse into a robust interactive network of commercial activity. From his first water journey from Antioch, we see the possibility of a growing appetite for Far Eastern goods alongside regional agricultural and refined goods moving west to Anatolia. Next, we see refined goods moving east from Corinth to Ephesus after crossing over the Troas/Phillipi water route, which connected Asia to Europe on his second journey. Then, as he again returns from Greece, on his following itinerary, as he coasts east along the southwestern seaboard of Anatolia, his trip is typically punctuated with several commercial stops before arriving at Patara. At Patara, Paul boards a ship likely loaded with metals heading south for Tyre and Caesarea; the unloading of cargo on the Phoenician coast for distribution in the eastern Mediterranean shows that trade flow was not limited to Eastern, African, and Egyptian goods moving north and west.

Finally, while the Alexandrian ships loaded with grain for Rome reflect Rome's ongoing consumption and draw of goods, Paul's final journey reveals several things about Caesarea and trade in the Roman world. That Caesarea, serving its dual role as a military post and commercial hub, was the place Paul was held prisoner and from which he would leave for Rome, itself reveals its port was an important means of conveyance. Moreover, that he boarded a merchant ship planning a stop at Sidon to add on luxury goods for Anatolia reveals the diversity of Caesarea's services and its commercial cooperation with neighboring interests. Consequently, while Caesarea was actively sending and receiving goods from Anatolia and participated in a wide network of trade that benefited Rome, Paul's trips confirm a growing interregional demand and export of products that increasingly moved in all directions across the Mediterranean.