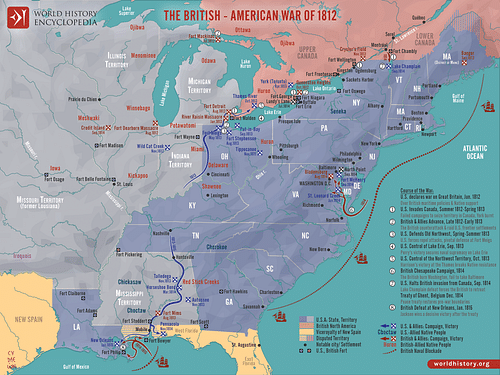

The Battle of Lake Erie (10 September 1813), also known as the Battle of Put-in-Bay, was a decisive naval engagement in the War of 1812. It saw a squadron of US ships, under Oliver Hazard Perry, defeat a British squadron near Put-in-Bay, Ohio, ultimately leading to the American domination of Lake Erie and allowing for their recapture of Detroit.

Background

In the spring of 1813, the sounds of constant shipbuilding echoed off the waters of the Great Lakes. For almost a year now, the nations of the United States and the United Kingdom had been at war, with the fate of Canada hanging in the balance. Two US invasions of the British colony had already been repelled before the Americans shifted their focus to the Great Lakes, particularly the mighty Lake Ontario. Both sides knew that naval superiority would give the Americans an advantage in their next invasion attempt, leading both sides to race to put new ships in the water. By June, the Americans and the British each had naval squadrons patrolling Lake Ontario, however, neither squadron moved to attack the other. Since naval actions tended to be unpredictable – reliant as they were on external factors like the wind – neither squadron wanted to take the initiative and risk its own destruction. Instead, the squadrons just danced around one another, waiting for the other to make the first move.

Ships were also being built on Lake Erie, even though it was considered by both sides to be of secondary importance to Lake Ontario. Currently, Lake Erie was under the control of the British, who had seized it early in the war and had used it to help maintain their occupation of the Michigan Territory after the Siege of Detroit (15-16 August 1812). If the Americans wanted to retake Michigan, they would need to first establish dominance on Erie, leading them to begin a shipbuilding program on this lake as well. Command of this burgeoning US squadron was given to Oliver Hazard Perry, a 27-year-old naval officer from Rhode Island, who had already accumulated a great deal of naval experience during his service in the Quasi-War and the First Barbary War. In late March, Perry arrived at Presque Isle, where the new ships were being built at a frantic pace. Crews of axmen had already laid low the surrounding forests to gather enough wood for the vessels, often chopping nonstop from sunrise to sunset; so swift was their work that, in the words of historian Pierre Berton, "a tree on the outskirts of the settlement can be growing one day and part of a ship the next" (508).

Still, there were frustrating delays. Food shortages led the workers to go on strike, while materials ordered from far-off locations – canvas from Philadelphia, for example, or spike rods from Buffalo – took a while to arrive. When the ships finally neared completion in July, Perry faced a new problem: a lack of sailors. Commodore Isaac Chauncey, the commander of the Lake Ontario fleet and Perry's direct superior, had kept all the best sailors for himself, sending Perry only those he considered to be the dregs of his squadron. Eager to attack as soon as possible, Perry spent the following weeks pleading with Chauncey for more men, writing, "For God's sake…send me men and officers" (Berton, 523). In August, Chauncey finally relented and sent Perry 89 experienced men. Among these reinforcements was Lt. Jesse Elliott, whose recent exploits, including the daring capture of two British brigs, had turned him into a war hero. Perry was so happy to have these men that he put Elliott in command of one of the new ships, USS Niagara, and let him choose his own crew. Elliott, an arrogant and ambitious man who felt slighted that he had not been given Perry's job, chose all the best men, leaving the other captains to grumble that the ships were unequally manned now that all the best sailors were on the Niagara.

On 31 August, Perry received more welcome news: General William Henry Harrison, commander of the US Army of the Northwest, had sent him 100 Kentucky riflemen to act as marines in the coming battle. The Kentuckians, many of whom had never seen a ship before, marveled at each and every detail, climbing the masts and exploring the holds before Perry ordered them on deck to teach them naval etiquette. By early September, Perry's small squadron was ready for battle, or as ready as it was likely to get. Of his nine vessels, three were brigs (Lawrence, Caledonia, Niagara), five were schooners (Ariel, Scorpion, Somers, Porcupine, Tigress), and one was a sloop (Trippe). His flagship, USS Lawrence, was named after his friend, Captain James Lawrence, who had recently been mortally wounded aboard the USS Chesapeake in a single-ship action off Boston. Lawrence's last words – "Don't give up the ship" – were sewn in white letters on a dark blue battle flag that Perry intended to hoist onto his masthead as a signal for action. With his ships in the water and his men on the decks, Perry now had only to wait for the coming fight.

Preparations

As work on Perry's ships neared completion, the British squadron in Lake Erie sought to destroy them before they could be launched. On 20 July, British Commander Robert Heriot Barclay sailed his six vessels to Presque Isle, only to find that his ships could not get across the sandbar to attack the American ships in the harbor. Frustrated, Barclay's squadron sat outside the sandbar for nine days, maintaining a limp, half-hearted blockade that was ultimately lifted once the British ran out of supplies. Once the British ships had gone, Perry carefully moved his vessels across the sandbar; this was done by taking the guns off the ships, making them lighter, and raising them up between two barges referred to as 'camels'. In this manner, Perry's ships were across the sandbar and ready for action when Barclay returned at the beginning of August. By the end of the month, the American ships had established an anchorage at Put-in-Bay, Ohio, from where they could effectively blockade Amherstburg, the main British outpost in the region.

Thus, Perry was forcing Barclay's hand; to relieve the pressure on Amherstburg, the British would have to assault the American position at Put-in-Bay. Like his opponent, Barclay was a lifelong sailor. Only a year younger than Perry, he had entered the Royal Navy at the age of 12; he had wept as he went to join his new frigate, lamenting that, "I am on my way to the sea and will never see my father, mother, brothers and sisters again" (Berton, 533). Barclay went on to serve under Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar (21 October 1805) and lost his arm a few years later as he was boarding a captured French ship. Now, in command of the British squadron on Lake Erie, he was determined to finally make a name for himself after all his years of service and sacrifice. His six vessels included two fully rigged ships – his flagship Detroit and Queen Charlotte – as well as the brig General Hunter, the schooners Lady Prevost and Chippewa, and the sloop Little Belt. Although he was outnumbered, Barclay did outgun the Americans and, more importantly, outranged them; the British had long guns that could accurately fire up to 900 yards (820 m), while the American cannons could only fire up to 450 yards (410 m).

Barclay decided to hang his hopes upon these long-range cannons. His plan was for his ships to concentrate all fire upon Perry's flagship, the Lawrence. Once it was knocked out of commission, the British could pick apart the other American ships piecemeal. Perry, meanwhile, was well aware of the British long-range guns; his plan, therefore, was to get his ships into close quarters as soon as possible, to reduce the amount of time they would need to spend at the mercy of enemy fire. Perry planned for his two largest vessels – Lawrence and Niagara – to target and attack the two largest British ships, Detroit and Queen Charlotte, believing that his own ships would have much greater firepower at close range.

The Battle Gets Underway

Just after sunrise on the morning of 10 September 1813, the lookout aboard the USS Lawrence spotted six silhouettes on the horizon, creeping toward the American anchorage at Put-in-Bay. Upon realizing that this was the British squadron, the lookout called "sail ho!" and the deck came alive with men, rushing to their stations. Perry, who moments before had been confined to his bunk with a chronic fever, was soon on his feet, barking orders. The flag bearing Captain Lawrence's final words was hoisted, as were signals to the other ships to form a line of battle; Perry was going to take the fight to the enemy. Initially, the wind was blowing against him, and for two hours, the American ships struggled to sail forward against it. Then, at around 10 a.m., the wind shifted and began blowing from behind the American vessels, carrying them forward. Perry spent his time walking around the deck, inspecting the guns while talking and joking with his crew. Upon approaching a group of gunners who had removed their headgear and tied bandanas around their foreheads, Perry laughed. "I need not say anything to you," he said. "You know how to beat these fellows" (Berton, 536).

The British ships, meanwhile, sat still, waiting to receive the approaching vessels; one crewman would later recall that the uncomfortable stillness leading up to the battle was like "the awful silence that precedes an earthquake" (ibid). Then, at 11:45 a.m., the American ships came within range of the Detroit, which opened fire with its long-range cannons. The first cannonball burst through Lawrence's bulwarks, sending a flurry of splinters into an unlucky sailor, killing him. Perry signaled for the other ships to close the distance and find their targets. But, for the next half hour, the guns of his own flagship remained out of range, rendering the Lawrence helpless beneath the fury of the Detroit's bombardment. To make matters worse, Perry's smaller schooners and sloop had fallen behind, leaving his three brigs to face the enemy alone for the time being. The Lawrence was at the front of the American line, followed by the Caledonia, with Lt. Elliott on the Niagara taking up the rear.

At 12:15 p.m., the Lawrence finally came within range of the Detroit, coming so close that the British believed the Americans were preparing to board. On Perry's command, the Lawrence unleashed a hail of canister shot that raked the British decks with pieces of metal, shredding through the flesh and bone of British sailors. The Detroit was quick to return fire, and, for the next hour, the two flagships traded devastating broadsides at close range. Pierre Berton describes the hellish carnage that descended upon the American ship:

Above the shrieks of the wounded and the dying and the rumblings of the gun carriages come the explosion of cannon and the crash of round shot splintering masts, tearing through bulwarks, ripping guns from carriages. Soon the decks are a rubble of broken spars, tangled rigging, shredded sails, dying men. And over all there hangs a thick pall of smoke, blotting out the sun, turning the bright September noon to gloomy twilight.

(538)

Elsewhere, the fight was also getting underway. The second largest British ship, the Queen Charlotte, moved forward to aid the Detroit in its duel with the Lawrence. It was briefly challenged by the American brig Caledonia, which unleashed a bombardment that killed both the captain and the first officer of the Queen Charlotte. However, the Caledonia's captain was not willing to risk getting much closer to the more powerful Queen Charlotte and let it continue on its way. By 1:30 p.m., the Queen Charlotte had added its firepower to the Detroit and was shredding the Lawrence with cannon and grapeshot. By now, the decks of the American flagship were slick with blood and brains, which soaked into the wood and seeped down to drip onto the faces of the wounded men below deck. An hour later, the Lawrence had been reduced to a floating hulk and did not seem capable of holding out much longer.

'Don't Give Up the Ship'

As the Lawrence was taking a ghastly beating, the second most powerful American ship, the Niagara, held back; its commander, Lt. Elliott, had shortened sail, leaving the brig floating still in the water. It is not known exactly why Elliott refused to join the battle at this stage, as his previous conduct proved that he was no coward. Elliott himself would later claim that he was simply following orders to maintain his position in the line of battle; since ahead of him, the Caledonia had slowed to a crawl, Elliott would maintain that he had no orders to sail around the other brig and join the fight. But others would put forward a more sinister explanation, claiming that the ambitious Elliott wanted to let the Lawrence absorb the brunt of the damage before swooping in and saving the day at the last moment.

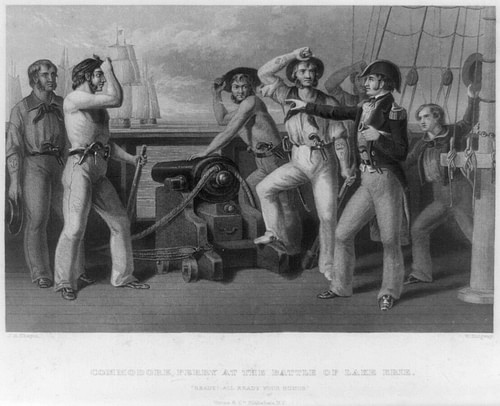

In any case, by 2:30 p.m., the Lawrence was alone and on the verge of surrender, four out of every five men having been killed or wounded. Perry – who had been miraculously uninjured – was unwilling to admit defeat and, spying the undamaged Niagara in the distance, decided to row over and continue the fight from aboard its decks. Taking four men and his battle flag with him, Perry leaped into a boat and rowed to the Niagara, as bullets and cannonballs whizzed around him; at one point, when the rowboat was punctured by a cannonball, Perry simply took off his jacket to plug the hole. Finally, Perry reached the Niagara and, taking command of the ship, sent Elliott off in the rowboat to hurry along the schooners and sloop, still far behind. Perry then hoisted his battle flag and sailed forward, to rush to the Lawrence's rescue.

At around 3 p.m., Barclay tried to maneuver the battered Detroit to meet the oncoming Niagara. But Elliott had brought the schooners into the fray, and was now directing their fire into the British ship; Barclay was incapacitated by a round of grapeshot that tore through his shoulder, and his first officer was killed. As the wounded Barclay was brought below deck, command passed to Lt. George Inglis, who tried to bring the Detroit around. But as it attempted this maneuver, the Detroit accidentally collided with the Queen Charlotte, and the two ships became entangled. It was at this moment that the Niagara opened fire, its cannonballs tearing through the two British ships with devastating effect.

Perry unleashed a broadside on the port side as well, hitting the smaller British vessels Chippawa and Lady Prevost; the captain of the Lady Prevost, struck in the face with a musket ball, went mad with pain and stood on the bloodsoaked deck, howling. Before long, every British officer had been killed or wounded, and, one by one, the British vessels struck their colors. After three hours it was all over; Perry had not only won but had also captured an entire squadron of British ships, a rare feat in the post-Trafalgar world. Perry himself would state as much in his hastily scribbled message to William Henry Harrison, a two-sentence report that would soon become famous: "We have met the enemy and they are ours. Two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop".

Aftermath

The Battle of Lake Erie had been a bloody affair, having cost the Americans 123 casualties (27 dead and 96 wounded) and the British 440 casualties (41 dead, 93 wounded, 306 captured or missing). Perry's personal surgeon, Dr. Parsons, would spend the rest of the afternoon and most of the night sawing off limbs of wounded sailors, both American and British. Perry proved himself to be a magnanimous victor, treating the captured British sailors with respect and dignity; Barclay would later report that "since the battle [Perry] has been like a brother to me" (Berton, 549). Although Barclay would survive his injuries, the damage would be permanent, and he would never again be able to lift his one remaining arm. Perry himself would be hailed as a war hero for his conduct in the battle and would be immortalized in the history of the US Navy. He and Elliott would accuse one another of not doing their duty during the battle, leading to a years-long argument between the two men in the country's newspapers.

The Battle of Lake Erie had a significant impact on the broader War of 1812. It gave the Americans control of the lake, forcing the British to abandon Detroit and their other gains in the Michigan Territory and retreat up the Thames River. They would be pursued by General Harrison and his Army of the Northwest, leading to the climactic Battle of the Thames (5 October 1813) and the death of the Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh. The Battle of Lake Erie, therefore, helped ensure that Michigan would remain a part of the United States, and it neutralized threats to other western US states like Ohio and Pennsylvania. Additionally, Perry's victory enhanced the prestige of the fledgling US Navy, giving the Americans some measure of pride in an otherwise demoralizing war.