The Battle of the Thames (5 October 1813), or the Battle of Moraviantown, was a decisive engagement in the War of 1812, in which a US army under General William Henry Harrison defeated a British and Native American force in Upper Canada. The battle resulted in the death of the Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh and the dissolution of his intertribal confederacy.

Background: The Struggle for Michigan

On 16 August 1812, less than two months after the War of 1812 had been declared, the British captured the major US outpost of Fort Detroit without a fight, giving them control of the entire Michigan Territory. This decisive victory could not have been achieved without the help of several northwestern Native American nations, who had sided with the British in order to resist the aggressive westward expansion of the United States. Under the charismatic leadership of the Shawnee chieftain Tecumseh, these Native American nations were in the process of joining together in a new intertribal confederacy, with the goal of recovering lands they had lost to the US after the disastrous Battle of Fallen Timbers (20 August 1794). Britain was eager to support this new confederacy, viewing it as a potential buffer state between the US and Canada, and promised to help set up the Native Americans on lands west of the Ohio River.

The United States, anxious as it was to prevent a hostile, British-backed Native American confederacy from arising on its western frontier, was determined to nip the threat in the bud by reconquering Michigan. This task was allotted to Major General William Henry Harrison, the popular hero of the Battle of Tippecanoe, and his newly formed Army of the Northwest, comprised mainly of volunteers from Kentucky and Ohio. In early October 1812, Harrison set out towards Detroit, but his progress was hindered by poor logistics and bad weather. Forced into winter quarters by January 1813, Harrison faced additional difficulties when the leading column of his army – at the small settlement of Frenchtown, Michigan, on the River Raisin – was attacked and defeated by a British and Native American force. After the battle, the British soldiers withdrew to Detroit, taking their able-bodied captives but leaving behind those Kentuckian prisoners who were too wounded to walk. When night fell, many of these wounded Kentuckians were massacred by Potawatomi warriors allied with the British, who desired vengeance for their villages that had been burned by Harrison's army during its advance through Ohio.

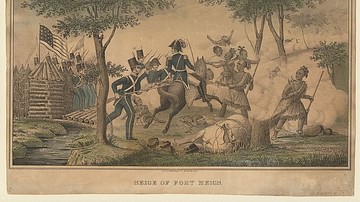

Harrison, upon learning of the defeat at the Battle of the River Raisin, withdrew the rest of his army to the Maumee River, where he hastily built Fort Meigs in February 1813. For the next several months, the Army of the Northwest remained holed up in the fort, even withstanding a brief siege in May. Before he could continue his advance toward Detroit, Harrison knew that the Americans needed to gain control of Lake Erie; possession of the lake would allow them to more easily reinforce and resupply their army in Michigan. With this goal in mind, the Americans built nine vessels on the lake, which were placed under the overall command of Master Commandant Oliver Hazard Perry.

In late August, Perry moved his naval squadron to Put-in-Bay, Ohio, a position from which he could blockade the main British outpost along the lake, at Amherstburg in Upper Canada (present-day Southern Ontario). A squadron of six British ships, under Robert Heriot Barclay, sailed out to meet this threat, culminating in the Battle of Lake Erie (10 September 1813), in which Perry prevailed, capturing the British vessels; as Perry himself would put it in his report to Harrison, "We have met the enemy and they are ours." With the Americans in control of Lake Erie, Harrison was free to resume his advance toward Detroit. In mid-September, his army marched into Michigan along the lakeshore, supplied by Perry's victorious ships in the lake.

Procter's Retreat

Even before news of the defeat on Lake Erie reached him, Major General Henry Procter – commander of the British forces in the northwestern frontier – was anxious to retreat. Thanks to Perry's blockade, his position at Amherstburg had already been precarious. Food had been running dangerously low, and the outpost itself was underdefended, its cannons having been used to outfit Barclay's ill-fated fleet. Now, upon learning that the Americans were in control of Lake Erie, Procter saw his position as hopeless. Consulting his maps, he decided to pull his forces back to Burlington Heights, a stronger British position at the western end of Lake Ontario. This would, however, require him to abandon Detroit and the Michigan Territory, and would risk upsetting his Native American allies in the region, whose support he relied on. Outnumbered by Harrison's oncoming force, Procter saw no other way and decided to go ahead with the retreat.

When Tecumseh learned of Procter's decision, he flew to him in a rage. The Shawnee chieftain had been fighting White Americans his whole life. His elder brother, Cheeseekau, who had been a father figure to him, had been killed fighting US soldiers in the 1790s, and Tecumseh himself had fought at Fallen Timbers and witnessed the humiliations to his people that followed. Tecumseh, moreover, had a personal score to settle with Harrison, who had tried to push the Native Americans off their hunting grounds during his time as governor of Indiana and had beaten Tecumseh's Confederacy at Tippecanoe. Retreat, even for tactical reasons, was off the table for Tecumseh, who feared that such an action could doom his fragile confederacy. Through an interpreter, Tecumseh urged Procter to reconsider, telling him:

You always told us to remain here and take care of our land…you always told us you would never draw your foot off British ground. But now, Father, we see that you are drawing back, and we are sorry to see our father doing so without seeing the enemy. We must compare our father's conduct to a fat animal that carries its tail upon its back…our lives are in the hands of the Great Spirit; we are determined to defend our land; and if it is his will, we wish to leave our bones upon it.

(quoted in Berton, 557)

These words affected Procter, who knew he could not risk losing his Native American allies. To retain Tecumseh's support, the British general offered a compromise: they would retreat only as far as the forks of the Thames River in Upper Canada where they would make a stand, with Procter promising that the British would "mix our bones with [your] bones" (ibid). Tecumseh reluctantly agreed to join, although two-thirds of his followers, disgusted by what they perceived as Britain's betrayal, refused; led by the influential Wyandot chief Walk-in-the-Water, hundreds of Native Americans returned to their homes. Tecumseh himself, though he had become resigned to the retreat, still viewed the prospect with a sense of dread, telling one of his followers that "we are going to follow the British, and I feel that I shall never return" (ibid). On 23 September, the British abandoned Detroit, setting fire to its fort and storehouses. On 27 September, they left Amherstburg as well, beginning their retreat up the Thames River.

Harrison Closes In

On the same day that Procter left Amherstburg, Harrison arrived in Detroit "amidst the joyful acclamations of the people" (quoted in Taylor, 244). After leaving a garrison behind, he crossed over the Detroit River into Canada, seizing control of Amherstburg as well. Then, with 3,500 soldiers under his command, he began his push up the Thames River, in pursuit of Procter's retreating army. Most of Harrison's men were Kentuckians, fresh volunteers eager to avenge the deaths of their friends and neighbors who had been slaughtered by Native Americans at the River Raisin; the slogan ‘Remember the Raisin' had been echoed at recruitment drives across the frontier settlements, leading more men from Kentucky to enlist in the army than from any other state. Isaac Shelby, the 63-year-old governor of Kentucky, personally led five brigades in Harrison's army while Colonel Richard Mentor Johnson, a sitting Kentucky congressman, led some troops as well. The eager Kentuckians moved swiftly, covering many miles each day.

The British, by contrast, moved slowly. Mud-churned roads and heavy baggage slowed their retreat to a crawl, while the sleep-deprived men were forced to subsist on half-rations. To make matters worse, Procter, who was travelling ahead of the men with his wife and family, had failed to make clear where they were headed; fearful that the soldiers would mutiny if he told them about the promise he had made to Tecumseh to fight on the Thames, he had elected to keep silent instead. Discontent soon turned to outrage; at one point, Major Adam Muir suggested that Procter's second-in-command, Colonel Augustus Warburton, should depose the general and take command himself. When Warburton refused, Muir shouted that "Procter ought to be hanged for being absent and Warburton hanged with him for refusing responsibility" (Berton, 571). It was amidst this tense atmosphere that the British neared Moraviantown on the night of 4 October. Situated along the banks of the Thames, Moraviantown was a small Indian mission village, which consisted of a church, a school, and 60 log buildings. Aware that Harrison was quickly catching up to him, Procter knew that this would be the area where he would have to make his stand.

Battle

Just before daybreak on 5 October 1813, the exhausted British soldiers stumbled from their tents to discover that the Americans were bearing down upon them and that it was time to move. The men barely had enough time to wolf down their half-cooked breakfasts before they found themselves marching two and a half miles (4 km) in the cold, predawn gloom. When they finally reached the riverside, Procter ordered them to halt and organized them into a line of battle. The roughly 800 British regulars, most of whom were from the 41st Regiment of Foot, held the left flank along the riverbank and were covered by a single 6-pounder cannon. On the right flank stood Tecumseh and approximately 500 Native Americans, positioned in a small swamp within a light forest of maples and oaks. As the first rays of morning light filtered through the trees, Tecumseh rode down the line, shaking hands with the British officers and men. One soldier would never forget the sight of the great Shawnee chieftain, remembering above all his "flashing hazel eyes" (Berton, 576).

Harrison, meanwhile, had moved his army across the river. The first casualty of the day occurred when William Whitley, an old Kentucky pioneer and Harrison's leading scout, shot a Native American from across the river and proceeded to scalp the corpse. "This is the thirteenth scalp I have taken," Whitley boasted, "and I'll have another by night or lose my own" (ibid). Whitley was hardly the only bloodthirsty Kentuckian, as many of the US troops had counted friends or relatives amongst those slain on the River Raisin, and were eager to exact revenge both on the Native Americans who had committed the slaughter and on Procter, the man who had allowed it. After forming his men up about half a mile (800 m) in front of the British line, Harrison agreed to let Colonel Richard Mentor Johnson's regiment lead the charge; Johnson, in turn, split his regiment into two battalions. The first, under his younger brother Lt. Colonel James Johnson, would attack the British regulars on the left flank, while the older Johnson would personally lead the second battalion against the Native Americans.

When everything was ready, the American bugle sounded, signaling the advance. The younger Johnson led his battalion toward the line of British regulars who were tired, hungry, and completely disheartened. The regulars got off only a single musket volley before the Kentuckians reached them, their eyes ablaze with fury, shouting, "Remember the Raisin! Remember the Raisin!" Almost immediately, the British threw down their muskets and fled, running off into the woods, having never even bothered to fire their cannon. For a moment, Procter tried to rally his troops before realizing that the battle was lost; fearing for his safety should he be captured, he decided to join his men in their flight. On the left flank, the battle was already over, only five minutes after the American bugle had sounded and initiated the charge. On the right flank, Richard Mentor Johnson was preparing his own attack. His plan was bold and, quite literally, suicidal; 20 mounted volunteers would ride past the Native Americans and draw their musket fire. Then, as the Natives paused to reload, the rest of Colonel Johnson's men would charge them. Johnson announced that he would ride with the 20 men, as would the scout William Whitley.

So, once Johnson gave the order, the 20 riders galloped toward the Native Americans in a mad charge. The warriors took the bait and fired a musket volley, immediately knocking most of the riders off their horses. 15 were killed or mortally wounded, including Whitley, whose bullet-strewn corpse came to rest in the mud. Johnson had been hit five times, but would survive; as his companions pulled him away from the battlefield in a blanket, the rest of his Kentuckians surged forward, striking the Native Americans as they reloaded. What followed was a desperate hand-to-hand struggle, as more and more US soldiers poured into the fray. For much of the fight, the melodic voice of Tecumseh could be heard above the din, shouting encouragements to his men. Suddenly, that voice was silenced, as Tecumseh was slain in the thick of the fighting. Upon realizing that their leader had been killed, the Native Americans let out a mournful yell and fled into the woods. And so, with Tecumseh's death, the Battle of the Thames was over. Historian Pierre Berton eloquently describes the scene after the fight as follows:

As the late afternoon shadows gather, a pall rises over the bodies of the slain. There are redcoats here, their tunics crimsoned by a darker stain, and Kentuckians in grotesque attitudes that can only be described as inhuman, and Indians, staring blankly at the sky…but one corpse is missing. Elusive in life, Tecumseh remains invisible in death. No white man has ever been allowed to draw his likeness. No white man will ever display or mutilate his body. No headstone, marker, or monument will identify his resting place. His followers have spirited him away to a spot where no stranger, be he British or American, will ever find him – his earthly clay, like his own forlorn hope, buried forever in a secret grave.

(584)

Aftermath

When the smoke finally cleared, around 27 US soldiers lay dead on the battlefield, another 57 having been wounded. British casualties amounted to around 18 killed, 25 wounded, and 565 captured, while their Native American allies suffered 33 dead and an unknown number of wounded. Of course, Tecumseh's body was never found – the day after the battle, Kentucky volunteers flayed a Native American corpse that they claimed belonged to the Shawnee chieftain, but this was debunked by a local boy who had seen Tecumseh the day before. Many men would take credit for Tecumseh's killing; the family of William Whitley would boast that their relative had killed Tecumseh before dying himself, while Richard Mentor Johnson's assertion that he had been the one to do it would help propel him to the vice presidency in 1837. Whatever the case, it soon became clear that Tecumseh was indeed dead. On 14 October, several Native American nations that had been a part of his short-lived confederacy – the Miami, Potawatomi, Wyandot, Wea, Ottawa, and Ojibwe – sent chiefs to Detroit to make peace with the US, promising to return all prisoners and to join the war against Britain. Tecumseh's dreams of a united Native American resistance against the United States, it seemed, had died with him.

Immediately after the battle, the victorious Kentuckians set about raiding Moraviantown. They did so against the pleas of the missionaries, who shouted that the only Native Americans who lived there were Christian pacifists; the Kentuckians, however, were driven by a hatred for all Native Americans and believed that the White missionaries who aided them were race traitors. So, the small, peaceful settlement of Moraviantown was razed to the ground, the first settlement to be intentionally destroyed in the war. With this last, senseless act of violence, the northwestern theater of the War of 1812 came to an end. Both Michigan and Lake Erie were in US hands, Tecumseh was dead, his confederacy was destroyed, and the British were on the defensive in Canada. Aside from a few minor skirmishes, the Michigan frontier would stay quiet for the rest of the war, though fighting would continue in Ontario and around the Chesapeake in the coming year.