How Death Came into the World is a legend of the Modoc nation whose ancestral lands once covered the region of modern-day northeastern California and southern Oregon, USA. Their story of the origin of death shares many similarities with those of other Native peoples of North America as well as with the ancient Greek myth of Orpheus and Eurydice.

The Modoc were 'discovered' by Euro-Americans c. 1820 in their ancestral lands of what is now southern Oregon and northern California. They are described by the American ethnographer James Mooney (l. 1861-1921) as a small band who were culturally isolated, which makes the similarities between How Death Came into the World and the Orpheus/Eurydice myth all the more interesting.

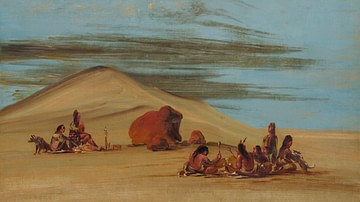

The Modoc had been living in the region for approximately 14,000 years before the arrival of the Euro-Americans but, by 1864, had been forcibly relocated to reservations, eventually two separate ones in the territories of modern Oklahoma and Oregon. They retained their stories, however, including How Death Came into the World, which is still told today.

The main character of the tale, Kumokums, is the Creator God of the Modoc (also known as Kemush, Kumokum, Kumush, Koomookumpts, Gmukamps) and his name is translated as "Old Man of the Ancients" or "Primeval Old Man", suggesting his existence from the beginning of time. In one version of the Modoc Creation Story, Kumokums travels to the Land of the Dead to select the spirits that would animate the people of four tribes of the region: the Shasta, the Warm Springs, the Klamath, and the Modoc. In How Death Came into the World, he again travels to the Land of the Dead but, this time, to bring back the spirit of his recently deceased daughter.

Native American Death Origin Myths

Native American origin myths concerning death are remarkably similar, even when the nations have had no known contact with each other prior to Euro-American contact and efforts to synthesize cultural beliefs as expressed in Native American literature. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman writes:

Most accounts of the origin of death accept the logic that space is limited on Earth and room needs to be made for new life. On the whole, the afterlife is regarded as a place much like this one but with more game, corn, or whatever was prized…Almost all Indian peoples believed in some plane of existence beyond the realm of the living, but descriptions of the afterlife differed greatly, and the issue of what happens to the soul after death was a highly complex one for many tribes.

(246)

As Zimmerman notes, there was no doubt – for many, if not all Native American nations – that the soul survived physical death and went on to another realm, but that did very little to help a survivor deal with the grief of their loss. Native American origin myths concerning death tried to assist with that by explaining how death came to be and how even those responsible for the decision suffered the same grief at their loss.

The basic paradigm involves a figure of some degree of authority who makes a decision concerning mortality, then loses someone close to them, and wishes to reverse their earlier judgment – but, once the choice has been spoken into existence, it cannot be taken back.

The Kiowa of the Plains Indians culture have a similar tale, sometimes given as How Death Came into the World and sometimes as Why the Ant is Almost Cut in Two, which follows this same model. In that story, the trickster figure Saynday (well-known from the Saynday tales) interacts with Red Ant as they discuss mortality and Saynday's concept of resurrecting the dead after four days. Red Ant rejects his proposal, claiming there are already too many living things on the earth and death is necessary to make room for those yet to be born or already living. Saynday agrees with her and decrees death as the final chapter of life on earth but, when Red Ant's son is killed, her grief is so intense she tries to kill herself, wishing she could have back what she had lost.

The Shoshone (Shoshoni) nation has a similar tale in which the central characters are Wolf and Coyote. Wolf suggests that death should be only a temporary state, which one could return from if the living enact a certain ritual that includes shooting an arrow beneath the deceased. Coyote rejects this plan, noting that there would then be too many of the living and resources would be spread too thinly. Wolf accepts Coyote's suggestion and decrees death as a permanent state, but when Coyote's son is killed, he comes to Wolf and asks that the decision be reversed. Wolf then reminds him that it was Coyote himself who insisted on death as a permanent state and that decision cannot now be altered.

Other Native American nations have similar origin stories for death, but the Modoc tale is unique in that it also provides an explanation of why the people had winter and summer camps, how their calendar was devised, and a detailed description of the Land of the Dead.

The story is also of interest to anthropologists, historians, and literary scholars for its similarity to the story of Orpheus and Eurydice from Greek mythology, which makes it stand out; as scholar Alice Marriott phrases it, "the Orpheus-Eurydice theme is unusual in North American Indian mythology" (190). There is no known record of interaction between the Modoc and anyone who would have known the Orpheus/Eurydice tale prior to contact between the Modoc nation and Euro-Americans, and How Death Came into the World is understood to pre-date that time as it seems to have already long been a part of the Modoc oral literary tradition.

Text

The following is taken from American Indian Mythology by Alice Marriott and Carol K. Rachlin. The loss of Kumokums' daughter, central to the tale, carries even greater weight in light of one version of the Creation Story in which she assists him in the act of fashioning the world and animating his creations with spirits from the Land of the Dead.

How Death Came into the World

Kumokums was living by himself near the Sprague River, and he began to get lonesome. He called all the animals together to talk to them.

"Let's build a village here," said Kumokums, "where we can all live together."

The animals liked the idea of a village, but some of them didn't like the place. "It's too cold here, and the grass is stubbly," remarked the deer. "I think we should go to Yainax."

"I like cold weather," Bear informed them. "That's when I can curl up and sleep as much as I want to. I'd rather stay here."

So, they discussed the matter, without ever really quarrelling, and at last Kumokums got tired of all the talking.

"Listen to me," he said. "I called this council, and I am its chief. We will have two villages. In the summer, we will all live in Yainax and in the winter we will live here on the Sprague River. Then everybody will be satisfied."

"How long is the summer and how long is the winter?" Porcupine asked.

"We ought to divide the year," Kumokums said. "Each can be six months long."

"But there are thirteen moons in the year," Porcupine argued. "What are you going to do with the odd one?"

"We can cut it up," Kumokums decided, "and use one half in summer and one in winter, for moving."

Everybody agreed that that was a good plan, and they would go along with it. It was summer then and the middle of the Moon When the Loon Sings, so they all packed and moved to Yainax.

Kumokums and the animals lived very happily for many years, moving back and forth between their winter and summer villages. But they were so happy and well-fed and contented that too many babies were beginning to be born. At last, Porcupine took matters into his own hands and went to talk to Kumokums about it.

"Kumokums," he said, "there are too many people around here. Our old people are dying off, and still there are too many people. We all know that, when people die, they go to a land beyond and, if they have been good, they are happy. Well, everybody in this village is well-fed and contented, so they have been good. Why not let them go to the Land of the Dead and they can be happy there?"

Kumokums sat and thought it over for a long time. Then he said, "I believe you are right. People should leave this earth forever when they die. The chief of the Land of the Dead is a good man, and they will be happy in his village."

"I'm glad you see it that way," said Porcupine, and waddled off.

Five days later, Kumokums came home from fishing up Sprague River and he heard a sound of crying in his house. He threw down his catch and rushed to the door in the roof of his house. He climbed down the pole ladder through the smoke hole. His daughter was lying on the ground and his wives were standing around, wringing their hands and crying.

"What has happened? What is the matter with her?" Kumokums cried. He loved his daughter very dearly.

"She has left us," his wives cried. "She has gone to the Land of the Dead."

"No! She can't do that!" Kumokums exclaimed, and he stroked his daughter's head and called her name. "Come back to me," Kumokums begged. "Stay with us here in our villages."

Kumokums went his wife through the village to bring in the most powerful medicine men. They sang and prayed over the girl's body, but no one could bring her back.

Finally, Porcupine came waddling backward down the pole ladder through the smoke hole.

"Kumokums," he said, "this is the way you said it should be. You were the one who set death in the world for everybody. Now you must suffer for it like everyone else."

"Is there no way to bring her back?" Kumokums pleaded.

"There is a way," said Porcupine, and Bear, who is as wise as Porcupine, nodded his head. "There is a way, but it is hard and it is dangerous. You, yourself, must go to the Land of the Dead, and ask it chief, who is your friend, to give you your daughter back."

"No matter how hard or how dangerous it is, I am willing to do it," Kumokums assured them. He lay down on the opposite side of the house and sent his spirit out of his body, away and away to the Land of the Dead.

"What do you want and whom do you come for?" the chief asked. He was a skeleton and all the people in his village were skeletons too.

"I have come to take my daughter home," Kumokums answered. "I love her dearly and I want her with me, but I do not see her here."

"She is here," replied the chief of the Land of the Dead. "I, too, love her. I have taken her into my own home to be my own daughter." He turned his head and called, "Come out, daughter," and a slim young girl's skeleton came out of the hole in the roof. "There she is," said the chief of the Land of the Dead. "Do you think you would know her now, or want her in your village, the way she is?"

"However she is, she is my daughter, and I want her," Kumokums said.

"You are a brave man," observed the chief of the Land of the Dead. "Nobody else who has ever come here has been able to say that. If I give her to you, and she returns to the Land of the Living, it will not be easy. You must do exactly what I tell you."

"I will do whatever you say," Kumokums said.

"Then listen to me carefully," said the chief of the Land of the Dead. "Take your daughter by the hand and lead her behind you. Walk as straight as you can to your own place. Four times you may press her hand, and it will be warmer and rounder. When you reach your own village, she will be herself again. But, whatever you do, do-not-look-back. If you do, your daughter will return to me."

"I will do as you say," Kumokums promised.

Kumokums held out his hand behind his back and felt his daughter's finger bones take hold of it. Together, they set out for their own village. Kumokums led the way. Once he stopped and pressed his daughter's hand. There was some flesh on it, and Kumokums' heart began to feel lighter than it had since his daughter died.

Four times Kumokums stopped and pressed his daughter's hand, and, each time, it was warmer and firmer and more alive in his own. Their own village was ahead of them. They were coming out of the Land of the Dead and into the Land of the Living. They were so close, Kumokums decided they were safe now. He looked back at his daughter. A pile of bones lay on the ground for a moment and then was gone. Kumokums opened his eyes in his own house.

"I told you it was hard and dangerous," Porcupine reminded him. "Now there will always be death in the world."