The American Revolution (c. 1765-1789) was a definitive event in Western history that saw the emergence of the United States and helped spawn additional waves of revolutions and societal upheavals on both sides of the Atlantic. Though the causes of the revolution are often presented simply – 'no taxation without representation' – its true origins were much more complex.

There were many different causes of the American Revolution, and although historians still argue over the degree of importance that should be accorded to each one, it is generally thought that the main causes were:

- Creation of an American identity, separate but closely entwined with that of Britain

- Parliament's policy of salutary neglect and its eventual abandonment of it

- A century of colonial wars

- Restriction of westward expansion

- 'Unjust' taxes

- A series of escalating conflicts between American 'Patriots' and British officials, including the Boston Massacre, Boston Tea Party, and Intolerable Acts

Certainly, there were many more causes, both major and minor, that should be considered, but these factors will hopefully give the reader a clearer understanding of why the American Revolution took place.

The American Identity

Perhaps no issue was more central to the origins of the American Revolution than that of the American identity. As late as 1775, on the eve of independence, many American colonists still considered themselves to be Englishmen, good and loyal subjects to the king – indeed, just before the Battle of Bunker Hill (17 June 1775), regiments of American rebels reported for duty by announcing that they were “in his Majesty's service” (Boatner, 539). It was, in fact, the belief in their own Englishness that led the colonists to value their liberty so fiercely.

Since at least the Glorious Revolution of 1689, the English prided themselves as the freest people in the world; compared to the absolutist monarchies, the constitutional monarchy of Britain was certainly more limited, with Parliament claiming the role as the voice of the king's subjects in matters such as taxation. According to the various legal documents that comprised Britain's abstract constitution – the Magna Carta (1215), for instance, and the Bill of Rights of 1689 – Britons were guaranteed certain rights such as self-taxation and representative government, which were exercised through the election of Parliament. Those who did not meet the property qualifications to take an active part in politics were considered virtually represented in Parliament.

When the first English settlers came to North America, they still considered themselves Englishmen – they spoke the same language, shared the same history, and owed allegiance to the same king. These colonists believed that they were still entitled to the 'rights of Englishmen', rights that were soon enshrined within their own colonial charters. Representative government, for example, was of great importance to the colonists; most colonies saw the establishment of legislative assemblies that were, at times, more powerful than the royally appointed governor. These assemblies were often responsible for the levying of taxes and the implementation of other policies, and, so long as these policies did not conflict with the interests of Britain, Parliament did not interfere.

So, as generations passed and the colonists became used to governing themselves, they began to develop separate identities underlying their Englishness. The Puritanical culture of New England, for instance, developed quite differently from the tobacco-based society of Virginia or the Dutch origins of New York. But despite all this, the colonists' 'rights of Englishmen' remained as cherished as ever, leaving the colonies in for a rude awakening should their perception of their own Englishness be challenged.

Salutary Neglect & Mercantilism

For most of the 18th century, the British Parliament dealt with the colonies through an informal policy known as 'salutary neglect'; Parliament allowed the colonies to govern themselves so long as they remained profitable to Britain. In an age increasingly defined by mercantilism, the idea of the colonies as 'profitable' to the mother country was of utmost importance; in 1651, Parliament passed the first of the Navigation Acts, which stipulated that only English ships could bring imported goods to England. Any goods exported from the North American colonies – timber, rum, tobacco, etc. – had to be shipped to Britain before they could be sent anywhere else. The Navigation Acts strengthened the colonies' dependence on Britain but led to tensions among the powerful merchant class in New England – by the 1660s, when the acts were first passed, these merchants had already established strong commercial ties with other colonies and other European countries and were loathe to give those up.

The colonists' resistance to the Navigation Acts marked a breach in the informal contract between them and Parliament – as punishment, Parliament sought to centralize British authority by consolidating the colonies into the Dominion of New England in 1689, overseen by a royal governor. This led to riots, including the 1689 Boston revolt, but the issue was resolved after the Glorious Revolution when the Dominion was dissolved. The policy of salutary neglect was reinstated, and the colonial merchants, for the most part, remained faithful to their economic duties to Britain.

Colonial Wars

Beginning in the mid-17th century and continuing until 1763, England's Thirteen Colonies were caught up in a series of wars that not only strengthened their ties to one another but also convinced them of their martial abilities. Indeed, most colonial towns had maintained militias in some form since their founding to protect their communities from the myriads of dangers that existed on the unforgiving North American frontier. These militias would be put to the test during the conflict known as King Philip's War (1675-1676), in which the Native American followers of Metacomet (known to the English as King Philip) waged war against the New England colonies. After a bloody struggle, the colonists ultimately prevailed, without assistance from England. The idea that New England had proven itself militarily self-sufficient led many New Englanders to begin to form identities for themselves that were separate from England, planting the first seeds of a distinct American identity. King Philip's War had also wrought much destruction to New England; in terms of deaths per capita, it remains the bloodiest conflict in American history. The trauma of the conflict and the efforts to rebuild once it was over also strengthened this New England identity.

This war was scarcely finished when England dragged the colonies into nearly a century of colonial wars with France. These wars – sometimes collectively called the French and Indian Wars – were all offshoots of wider conflicts that had begun in Europe and included King William's War (1688-1697), Queen Anne's War (1702-1713), King George's War (1744-1748), and the French and Indian War (1754-1763). Each war pitted England's colonies against the French, with many Native American nations forced to side with one belligerent or the other.

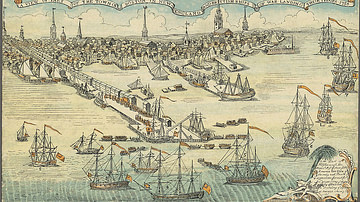

By the 1740s, colonists had begun to serve in 'provincial regiments', semi-professional units that were better trained than the common militias. Such provincial regiments ultimately made up the bulk of Britain's fighting forces in North America; the 1745 Siege of Louisbourg, for instance, was carried out largely by colonial troops from New England. Again, these military experiences tied the American colonists together through shared experiences and gave them a sense of purpose within the broader empire. Victories like Louisbourg convinced them that they were capable of success on their own merits – while the colonists still considered themselves Britons first and foremost, a separate, American identity was taking root beneath the surface. Moreover, the number of colonial soldiers trained by the British would prove significant, as many officers in the Continental Army had served previously with the British.

Limited Westward Expansion

Victory in the French and Indian War greatly expanded Britain's domain on continental North America. It now controlled the entirety of Canada and all the lands west of the Mississippi River. Many American colonists were eager to expand into these western territories, which they considered their rightful spoils of war. The conflict had broken out in 1754 as a dispute between Virginia and New France over lands in the Ohio River Valley. The colony of Virginia felt entitled to this land, not only because it had fought for it but because its economy depended on gaining access to fresh, fertile fields; tobacco, the colony's main cash crop, depleted the nutrients in the soil, leading Virginian planters to constantly seek out new fields. This was a top priority for Virginia, as evidenced by the fact that investors in the Ohio Company, a land speculation company, included some of the most prominent members of the Virginian gentry such as George Washington and the Lee family. Other colonies valued western lands for their own purposes, while individuals were enticed by the promise of a fresh start or property. Additionally, many French and Indian War veterans had been promised lands in the West.

As the colonists began to move into these lands, they came into conflict with the Native peoples of North America who already lived there. Land disputes between White settlers and Native Americans often boiled over into violence, with one major conflict – Pontiac's Rebellion – forcing Britain to expend valuable military resources to help the colonists put it down. The British, already so deeply in debt, did not want to have to rush to the colonies' defense every time they provoked a war with a Native American nation. Moreover, Parliament feared that the migration of colonists deep into the interior of the continent would make them less reliant on British goods and could foster ideas of independence. It was this desire to contain the Americans that led to the issuing of the Royal Proclamation of 1763, which forbade colonial settlement west of the Appalachian Mountains. Many colonists felt betrayed by this edict, which they interpreted as an infringement on the liberties that they so valued.

Taxation Without Representation

At the end of the French and Indian War, the British Empire found itself swamped with debt – in January 1763, the funded debt was as high as £122,603,336, carrying an annual interest of £4,409,797 (Middlekauff, 61). Since this came at a time when trade was depressed, the levying of new taxes seemed to be the only means of beginning to tackle the problem, but native Englishmen were already being taxed to their limit. In May 1763 in Exeter, for example, there were demonstrations to protest a new cider tax, leading Parliament to conclude that it could not impose many more new taxes on Englishmen without meeting stiff resistance. Naturally, the solution was to look to those living in other parts of Britain's vast empire, particularly those in the North American colonies. After all, the war had been largely fought in defense of these colonies, who had benefitted much from it. Additionally, an army was being sent to North America to keep the peace in the aftermath of Pontiac's Rebellion, a provision that Parliament believed the colonists should pay for.

At this time, there was little disagreement in Parliament that the colonies should be taxed. To be sure, for the last several decades, Parliament had been content to allow 'salutary neglect' but maintained that it had the right to set it aside whenever necessary. In 1764, Parliament tested the waters with the Sugar Act, which merely set out to enforce an existing tax on molasses and crack down on smuggling. This ruffled many feathers amongst American merchants since molasses played a huge role in the economies of the New England colonies. The merchants, finding that they could no longer bribe British customs officials now had to pay much more in taxes and began lambasting Parliament's interference in colonial affairs. Writers like Samuel Adams gained prominence by opposing the Sugar Act, arguing that the tax would amount to 'tributary slavery'. Since no Americans were represented in Parliament, they claimed, Parliament could not constitutionally tax them. Parliament disagreed, arguing that the colonists were no different from the Englishmen who were not qualified to partake in politics but were nevertheless virtually represented in Parliament.

However, it was Parliament's proposed Stamp Act that crossed the line in the minds of many colonists. This act imposed a tax – represented by a stamp – on all paper documents including legal contracts, marriage certificates, liquor licenses, newspapers, and even playing cards. The tax, though hardly ruining for most, would affect many more people than the Sugar Act had and was therefore much more visible. The voices of Adams and his fellow 'Whigs' grew louder. Merchants boycotted British goods, and rioters took to the streets in Boston where an underground group called the Sons of Liberty hanged British stamp distributors in effigy and burned their homes. Most importantly, a delegation of nine colonies met in New York City in October 1765 to discuss a unified, intercolonial response to the Stamp Act. This so-called Stamp Act Congress was the first instance of the colonies banding together in opposition to Parliament.

Rising Tensions

Parliament, shocked by the vitriolic response to the Stamp Act, decided to repeal it in early 1766. But in the same breath, it passed the Declaratory Act, which proclaimed that Parliament had the authority to legislate on behalf of all Britain's colonies “in all cases whatsoever”. This, in essence, meant that Parliament was not conceding the point to the colonists and it still claimed the right to impose policy on them. Around this time, Parliament also passed the Quartering Act of 1765, which required the colonies to provide food and lodging for British soldiers stationed in their towns. This appalled many colonists since standing armies had long been seen as an antithesis to liberty. For these reasons, tensions had not died down when Parliament passed the Townshend Acts in 1767-68, a new series of taxes that placed duties on items such as glass, paint, and tea. Once again, colonial legislatures condemned the taxes as unconstitutional, and many merchants joined together in new non-importation agreements against British goods. New rounds of riots in Boston got so bad that Parliament had to dispatch two regiments of soldiers there to keep the peace in October 1768.

The presence of British soldiers in Boston only exacerbated hostilities, especially once soldiers started to take jobs. This culminated in the Boston Massacre of 5 March 1770 when nine British soldiers, accosted by an angry mob, fired into the crowd, killing five. The soldiers were arrested and tried, with most of them acquitted thanks to the spirited defense of Boston lawyer John Adams. Shortly after the massacre, most of the Townshend Acts were repealed, and tensions began to die down; for a time, it seemed as though things might return to normal. Parliament had, however, kept the tea tax on the books, something that would become problematic in May 1773, when the British East India Company was granted a monopoly on all tea in Britain's colonies. Sam Adams and other Whigs argued that this was just an underhanded way for Parliament to get the colonists to pay their tax since, by purchasing East India Company tea, they would also be inadvertently paying the tea tax. This sparked outrage and led to the Boston Tea Party on 16 December 1773, when a band of Sons of Liberty dumped 342 crates of East India Company tea into Boston Harbor.

Intolerable Acts

Parliament looked to punish the insolent colony of Massachusetts for the Boston Tea Party, leading it to impose the five Coercive Acts in 1774. Known to the colonists as the 'Intolerable Acts', these policies were among the most direct causes of the American Revolutionary War. They included the closure of Boston Harbor to trade until the city had compensated the East India Company for the destroyed tea, and the suspension of representative government in Massachusetts, with a military official – General Thomas Gage – appointed to act as governor. The acts also stipulated that from now on, any British official accused of a crime in North America would be tried in Britain, which the colonists feared would lead to corruption and miscarriages of justice. The fourth act doubled down on the unpopular Quartering Act and required the colonies to provide housing for soldiers in unoccupied buildings (but not in private homes). The fifth policy was the Quebec Act, which expanded the territory of the new Province of Quebec to the Ohio River and promised the French Canadians that they could freely practice Catholicism. This greatly offended the Protestant colonists who wanted the land and had only recently been fighting the Canadians.

The Intolerable Acts were worrying to all 13 of the colonies; if Massachusetts could be treated in such a manner, what would prevent Parliament from treating the rest the same way? The acts were seen as a manifestation of Parliament's tyranny, a vindication of everything that the American Whigs had been afraid of. Legislative assemblies, like Virginia's House of Burgesses, condemned the Intolerable Acts and announced their solidarity with Massachusetts. For such insolence, the House of Burgesses was dissolved by Virginia's royal governor, only adding fuel to the fire. In late 1774, representatives from twelve colonies met in Philadelphia at the First Continental Congress, in which they hoped to devise a response to the Intolerable Acts. Along with new non-importation agreements, the Congress decided to ready local militias for a potential conflict. The Congress agreed to meet again in May 1775 if the situation had not improved, but prior to this second meeting, the first shots of the war were fired at the Battles of Lexington and Concord (18 April 1775), sparking the American Revolutionary War. This war would be the final thread that would weave an American identity separate from Britain, resulting in the foundation of a new nation.