George W. Crooks' Account of the Dakota War of 1862 is a narrative of the events leading up to the "Minnesota Massacre" known as the Dakota War of 1862, given by the Dakota gentleman George W. Crooks (l. c. 1856-1947) in 1937 when he was 81 years old. The account is archived with the Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota.

Crooks lived at Crow Creek near Redwood Falls, modern-day Minnesota, in 1862 when hostilities broke out between the Dakota and White settlers on 18 August 1862. Crooks was around six years old at the time, and his parents were among the Dakota who refused to join in the uprising, which was led, reluctantly, by Chief Little Crow (l. c. 1810-1863). Little Crow understood the revolt would be futile and many lives would be lost, but his people were starving due to failed promises of the US government and the underhanded practices of White business owners in the region.

According to the Sioux physician and author Charles A. Eastman (also known as Ohiyesa, l. 1858-1939), the Dakota Sioux guide and scout Tamahay (l. c. 1776-1864) warned Little Crow and those advocating for war against pursuing this course as it could only end badly for all involved. Little Crow already knew this, however, but felt he had been driven to a position where he had no other choice but to fight back.

Although Crooks was quite young at the time of the Dakota War (18 August to 26 September 1862), his account is considered a reliable primary document on the event which cost hundreds of lives on both sides and culminated in the forced relocation of the Eastern Dakota Sioux from Minnesota to South Dakota and the largest mass execution in US history when 38 Dakota Sioux men were hanged at Mankato, Minnesota, for their participation in the uprising in December 1862.

The Dakota War of 1862 & Crooks' Account

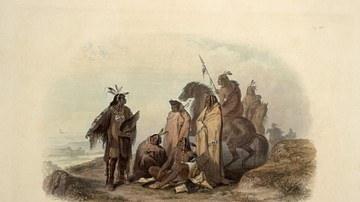

The Dakota ("friend" or "ally") Sioux nation of North America is divided between the Western Dakota and the Eastern Dakota, and the latter includes the Mdewakanton band, which, in 1862, was led by Little Crow (and which Tamahay was also a part of). The Mdewakanton Dakota of the Minnesota River Valley had surrendered most of their land to the US government through the Treaty of Mendota in 1851 and, in return, had been promised over $1 million, which was never paid.

They were removed from their ancestral lands and confined to a narrow strip along the Minnesota River where they were encouraged to become farmers and give up their semi-nomadic lifestyle of hunting and following the buffalo herds. They were given a stipend to pay for supplies from local merchants, but, as Crooks notes, the White shopkeepers frequently cheated the Dakota – who lacked understanding of the value of paper money – when they came to their stores, and this, along with a poor harvest in 1861, left the Mdewakanton Dakota starving.

On 17 August 1862, four young Dakota, who had failed to find food during a hunting expedition, killed five White settlers near Acton, Minnesota, and, although Little Crow advocated for a peaceful resolution in handing them over to authorities, he was overruled, and the war-faction of the assembly called on him to lead his people in righting the wrongs done to them. According to Eastman, Tamahay also called for peace, citing the futility of earlier conflicts such as Pontiac's War and the Black Hawk War, but was ignored.

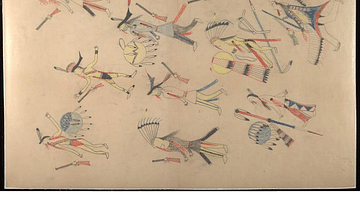

The war party struck at the Lower Sioux Agency the next day, 18 August 1862, murdering merchants who had intentionally cheated the Dakota as well as any other Whites they could find and any Dakota who took the side of the pioneer settlers. As Crooks notes, some of the Dakota who had been taken prisoner along with the White settlers, managed to get a message to General Henry H. Sibley (l. 1811-1891), who rescued the captive Dakota and Whites.

Hostilities continued until the Battle of Wood Lake on 23 September 1862 when Little Crow was defeated by US government forces. Afterwards, 303 Dakota men were sentenced to death by hanging, but, after a review of the case by President Abraham Lincoln, this was reduced to 39 convictions. Crooks cites this number, but, actually, one of the men was granted a reprieve, so 38 Dakota were hanged for their part in the uprising on 26 December 1862, the largest mass execution in a single day in US history. Little Crow survived the conflict but was killed by a local farmer in July 1863 who did not even know who he was, only that he was a Native American.

Dakota survivors of the conflict were deprived even of the small strip they had been granted when the US authorities had pushed them onto the reservation by the Minnesota River and were sent to Iowa and then to a reservation in South Dakota. In 2021, the Minnesota government and Minnesota Historical Society gave the lands fought over back to the Mdewakanton Dakota Sioux and offered an apology. The Mdewakanton Dakota continue to remember the Dakota War of 1862 and the hanging of the 38 freedom fighters annually, as Crooks, in his narrative, strongly suggests they should.

Text

The following is taken from U.S.-Dakota War of 1862: Primary Sources: Archives & Records, Dakota Conflict of 1862 Manuscripts Collections, Minnesota Historical Society, St. Paul, Minnesota, item # 55102, Accession # 8873. Changes have been made only to spelling and punctuation:

I was born at Crow Creek about halfway between the two towns now called Redwood Falls and Morton. Redwood at the time was a small trading post. My father and mother and the eleven children in the family lived a quiet and peaceful life until the time of the outbreak.

Our home was the same as the average white mans' home at the time. It was a brick building. We had some stock such as oxen, horses, cows, also chickens.

We dressed like Indians up to that time.

We did not know what paper money was. We had always had gold and silver coins. When the government changed from the coin to the paper money, the Indians, being accustomed to the gold coin, did not realize the value of paper currency.

When the Indians would go to the trading post for their supplies, the white people that owned the store, knowing that the Indians were entirely ignorant of the value of the new paper money, saw their opportunity to make a fortune for themselves. When an Indian would take a 20-dollar bill to the post for five dollars' worth of supplies, the post owners would keep the change, for they knew the Indians would not know the true value of the paper money they had given them.

When they were using the gold coin, their money from the government would last them from one payment to the next, but after the change of money, it was not long until the money was gone, and they had no food.

When they went back to the ones who had cheated them out of so much, they were refused credit. They could get no food. One of the store owners, by the name of Merrick, told an Indian by the name of Wa-Cin-Ko, whom he refused an appeal for food for his starving family, to go out into the fields and eat grass like the horses.

Others were refused aid in the same manner. At this time, four young Indian boys had gone hunting for some food to keep them from starving. They had gone some distance from the reservation. Having not much luck at hunting, the boys came to a farmhouse. They found some eggs, and being so hungry, one of the boys wanted to take the eggs. The other three, not wishing to be dishonest, appealed to the fourth to pay in some way for the eggs. The boy was becoming angry and told the others that he would show them how to deal with the white man, at the same time accusing his companions of being cowards.

Breaking the eggs with his foot, he drew his gun and shot down a cow that was grazing in the pasture. The farmer, seeing his property being destroyed, seized an axe, and ran out to drive the intruders away. He was shot down by the crazed young Indian. His wife, running to the aid of her husband, was shot down in like manner.

The boys, returning home immediately, reported their crime to Chief Little Crow, who in turn tried to persuade his Indian people to turn the boys over to the soldiers at Fort Ridgely to receive their punishment. However, the flaming anger that had been seething in the hearts of the Indians who had been treated so cruelly by the whites burst into flame now.

They refused to turn the boys over to the white men. They proceeded to get together and plan their revenge on the white people of the post. A few of them decided to go over to the post and kill the white people there. When the inhabitants of the post saw the Indians coming, they tried to protect themselves, but they were outnumbered by the Indians.

Merrick, the most hated of them all, seized his money and tried to escape, but was shot down before he could reach safety. Later, when his body was discovered, his mouth was stuffed with grass from the field through which he had tried to escape, thus had Wa-Cin-Ko gained his revenge on the man who had refused him food for his starving family and who told him to eat grass like the horses if he was hungry.

So started the horrible massacre that changed the beautiful Minnesota Valley into a bloody battlefield. The Indians fighting for the land that had always been theirs and meant life for them, and the white pioneers fighting for what they knew was not theirs and they had no right to claim.

However, they knew, if they could gain this land from the Indians, that they would be the possessors of the most fertile land in the country.

The pioneer people, seeing that the Indians could not be stopped, began to flee to protection. Most of them went to Fort Ridgely where they would be under protection of the soldiers stationed there.

Our some forty or fifty families who were civilized and not willing to fight were forced from our homes by the hostile Indians. We were taken to Wood Lake to be held captive with the white prisoners. After a few hours there, we were taken on to Camp Lee near Montevideo, there to wait with the white captives to be put to death by the warring Indians.

The dreaded time never came for, as darkness set in, a few of the men gathered together in one of the prison teepees and, by matchlight, an Indian by the name of John Robinson wrote a note to General Sibley, a man considered by the Indians as their friend.

Ironshield, an Indian runner, and an unknown brave, managed to escape from the camp and took two of the guards' horses and a white flag of truce which they had fashioned. They rode to General Sibley's camp. They were taken, upon their request, to see General Sibley, who could speak the Sioux Language fluently.

Informing General Sibley of the plight they were all in, they were rewarded by General Sibley's prompt action of sending his soldiers…

In the meantime, my mother, at the risk of her own life, brought the white women captives and their children to her teepee and dug a hole under the tent and put the children in to hide them. I and the other children stayed in that deep hole to hide from the wrath of the Indians who were holding us prisoners.

I personally heard the Indians who were guarding us say that they were going to kill all of us the following day, then move on. General Sibley's soldiers arrived in time to prevent them from carrying out their horrible plans. The warriors, seeing the soldiers coming in the distance, realized they were outnumbered and fled before the soldiers arrived at the camp. General Sibley had saved us from a horrible death at the hands of our enraged captors.

Knowing that the Indians were not to be stopped, runners were sent through other parts of the country to warn Indians and white people, who were ignorant of the uprising, that the Indians were on the warpath. They took heed to the warning and began to flee toward Minneapolis to get out of the danger zone.

In our midst was a man who was dearly loved by our tribe, our minister, S.D. Hinman. When we went to see if he was safe, we found him in a very bad condition. He had been attacked by the enemy and seriously wounded but, by the loving care of our Indian women, was nursed back to health.

We had much to thank him for in the years that passed by since that time. How many times he risked his life to save and protect the red-skinned people he loved and placed so much faith in. If only the white people who treated the Indians so outrageously could have had the same ideals, the same love for God and their fellow men in their hearts, that terrible, never-to-be-forgotten massacre would not have happened.

Now, to get back to our story: there were several families in each of the places I am about to name who were entirely innocent of any part of the outbreak: Faribault, Wabasha, St. James, and Hutchinson, yet these people who were innocent and unarmed through the entire outbreak were taken by the white soldiers and 39 were put to death on the gallows, a wholesale murder of 39 innocent Indians by the white people, the rest being put in prison at Dubuque, Iowa for a crime they did not commit.

Yet today, 74 years since that battle, the white people are prejudiced against the Indians who fought a losing battle to protect what was rightfully theirs against a band of foreigners who came to take their livelihood away from them.

Why don't the white speakers get up and speak against the World War [World War I] that took the lives of hundreds of thousands of American boys, the most horrible contest of war ever raged in the history of man, a war for the purpose of protecting their country, the same purpose the Indians fought for in the year 1862. Three of my own sons went to the World War to fight for the white people who are so prejudiced against them.

We Indians hold no grudge. We are the ones who lost. Today, we are under the hand of the government, the people who robbed us of our hunting and fishing, our free way of living, our land, and our freedom; yet the white people hold a grudge for what happened 74 years ago.

So, when the subject of the 1862 massacre comes up, why not take time to think and consider both sides of the story, before you condemn the Indians for trying to protect their own. Try to remember that the white people took everything the Indian had to live for away from him. Why not let the Indians live in peace, the few that are left of the vanishing American, for after all, they are the only real Americans. Why hurt the feelings of the Indians of today? You white people got what you wanted and forever ruined the lives of the red man.

I wish to say in closing that, though I am 81 years old and have been through a life of hardships, I hold no malice against the white people. My wife, Alice Crooks, and my six sons and two daughters are happy, contented, peace-loving people. We want to end our days here in the Minnesota Valley without any feelings against us by the White People. That is why I have tried in this little story to explain the injustice of the stories told by the white people about the massacre of 1862.