The Glooscap tales are legends of the Eastern Algonquin nations of the Wabanaki Confederacy – the Abenaki, Mi'kmaq, Passamaquoddy, Penobscot, and Wolastoqiyik – featuring the supernatural entity Glooscap, who is depicted sometimes as a god and sometimes as a trickster figure. Glooscap tales are still told among these communities, as well as others, today.

The Glooscap tales often share similarities with the Coyote tales of the Apache, the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne, Nih'a'ca tales of the Arapaho, Iktomi tales of the Sioux, and those of many other Native peoples of North America. Glooscap is usually depicted as supremely powerful and, unlike the others mentioned, a creator god of incredible power. He is also most often depicted as a force of ultimate good and cosmic justice – as opposed to his younger brother, Malsumsis, the Wolf, a champion of disorder – unlike the other figures referenced above who are given solely as trickster figures. Glooscap, a culture hero, exerted significant influence on the people who told his tales, and several sites in the region of the Wabanaki Confederacy are associated with him. The Mi'kmaq's Glooscap First Nation is named in his honor. Scholar Jennifer Atwin comments:

The Glooscap stories were used to teach values, traditions, and ways of life. Considering that the cultures of the Wabanaki were contained in language and traditions, the Glooscap stories were likely prevalent in their everyday lives.

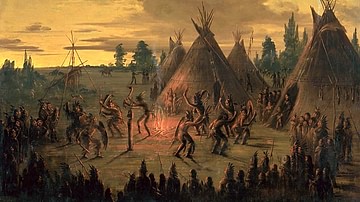

(1)

Glooscap tales entertained while also transmitting central cultural values. In Glooscap's Gifts, for example, the value of humility is emphasized, and this same theme is explored, comically, in Glooscap and the Baby in which the great Glooscap finds he cannot bend an infant to his will.

Text

The following text is taken from The Algonquin Legends of New England or Myths and Folklore of the Micmac, Passamaquoddy, and Penobscot Tribes by Charles Godfrey Leland (How Glooscap Made Elves Fairies, Man and Beasts, and the Last Day and Glooscap's Great Deeds) and from Myths of the North American Indians by Lewis Spence (Glooscap's Gifts and Glooscap and the Baby). The first two tales are attributed to the Passamaquoddy, the latter are unattributed but told by the tribes of the Wabanaki Confederacy as well as other Native American nations.

As Atwin notes, Leland had a fairly poor understanding of Wabanaki culture and Spence's commentary on Native American myth and legend is also challenged by modern-day scholars, but, even so, they preserved, in English, the tales of the Native American peoples they interacted with at a time when the policies of the US government were intent on eliminating them. Although writers like Leland and Spence often comment inappropriately, and even incorrectly, on Native American beliefs and customs, their work still has historical value, not only in preserving the myths and legends of the Native American nations but also in clearly illustrating how Europeans and Euro-Americans regarded the indigenous peoples of North America at the time these men were writing.

How Glooscap Made Elves, Fairies, Man, and Beasts, and the Last Day

Glooskap came first of all into this country, into Nova Scotia, Maine, Canada, into the land of the Wabanaki, next to sunrise. There were no Indians here then (only wild Indians very far to the west).

First born were the Mikumwess, the Oonabgemessũk, the small Elves, little men, dwellers in rocks.

And in this way, he made Man: He took his bow and arrows and shot at trees, the basket-trees, the Ash. Then Indians came out of the bark of the Ash trees. And then the Mikumwess said . . . called tree-man. . . . [the storyteller became unclear] Glooskap made all the animals. He made them at first very large. Then he said to Moose, the great Moose who was as tall as Ketawkqu's, [a giant] "What would you do should you see an Indian coming?" Moose replied, "I would tear down the trees on him." Then Glooskap saw that the Moose was too strong, and made him smaller, so that Indians could kill him.

Then he said to the Squirrel, who was of the size of a Wolf, "What would you do if you should meet an Indian?" And the Squirrel answered, "I would scratch down trees on him." Then Glooskap said, "You also are too strong,' and he made him little.

Then he asked the great White Bear what he would do if he met an Indian; and the Bear said, "Eat him." And the Master bade him go and live among rocks and ice, where he would see no Indians.

So he questioned all the beasts, changing their size or allotting their lives according to their answers.

He took the Loon for his dog; but the Loon absented himself so much that he chose for this service two wolves, — one black and one white. But the Loons are always his talebearers.

Many years ago, a man very far to the North wished to cross a bay, a great distance, from one point to another. As he was stepping into his canoe he saw a man with two dogs, — one black and one white, — who asked to be set across. The Indian said, "You may go, but what will become of your dogs?" Then the stranger replied, "Let them go round by land." "Nay," replied the Indian, "that is much too far." But the stranger saying nothing, he put him across. And as they reached the landing place there stood the dogs. But when he turned his head to address the man, he was gone. So he said to himself, "I have seen Glooskap."

Yet again, — but this was not so many years ago, — far in the North there were at a certain place many Indians assembled. And there was a frightful commotion, caused by the ground heaving and rumbling; the rocks shook and fell, they were greatly alarmed, and lo! Glooskap stood before them, and said, "I go away now, but I shall return again; when you feel the ground tremble, then know it is I." So they will know when the last great war is to be, for then Glooskap will make the ground shake with an awful noise.

Glooskap was no friend of the Beavers; he slew many of them. Up on the Tobaie are two salt-water rocks (that is, rocks by the ocean-side, near a freshwater stream). The Great Beaver, standing there one day, was seen by Glooskap miles away, who had forbidden him that place. Then picking up a large rock where he stood by the shore, he threw it all that distance at the Beaver, who indeed dodged it; but when another came, the beast ran into a mountain, and has never come forth to this day. But the rocks which the master threw are yet to be seen.

Glooskap's Great Deeds: How He Named the Animals & His Family

Woodénit atók-hagen Gloosekap [this is a story of Glooskap]. It is told in traditions of the old time that Glooskap was born in the land of the Wabanaki, which is nearest to the sunrise; but another story says that he came over the sea in a great stone canoe, and that this canoe was an island of granite covered with trees. When the great man, of all men and beasts chief ruler, had come down from this ark, he went among the Wabanaki. And calling all the animals he gave them each a name: unto the Bear, mooin; and asked him what he would do if he should meet with a man. The Bear said, "I fear him, and I should run." Now in those days the Squirrel (mi-ko) was greater than the Bear. Then Glooskap took him in his hands, and smoothing him down he grew smaller and smaller, till he became as we see him now. In after-days the Squirrel was Glooskap's dog, and when he so willed, grew large again and slew his enemies, however fierce they might be. But this time, when asked what he would do should he meet with a man, Mi-ko replied, "I should run up a tree."

Then the Moose, being questioned, answered, standing still and looking down, "I should run through the woods." And so it was with Kwah-beet the Beaver, and Glooskap saw that of all created beings the first and greatest was Man.

Before men were instructed by him, they lived in darkness; it was so dark that they could not even see to slay their enemies. Glooskap taught them how to hunt, and to build huts and canoes and weirs for fish. Before he came, they knew not how to make weapons or nets. He the Great Master showed them the hidden virtues of plants, roots, and barks, and pointed out to them such vegetables as might be used for food, as well as what kinds of animals, birds, and fish were to be eaten. And when this was done, he taught them the names of all the stars. He loved mankind, and wherever he might be in the wilderness he was never very far from any of the Indians. He dwelt in a lonely land, but whenever they sought him, they found him. He traveled far and wide: there is no place in all the land of the Wabanaki where he left not his name; hills, rocks and rivers, lakes and islands, bear witness to him.

Glooskap was never married, yet as he lived like other men he lived not alone. There dwelt with him an old woman, who kept his lodge; he called her Noogumee, "my grandmother." (Micmac). With her was a youth named Abistariaooch, or the Martin. And Martin could change himself to a baby or a little boy, a youth or a young man, as befitted the time in which he was to act; for all things about Glooskap were very wonderful. This Martin ate always from a small birch bark dish, called witch-kwed-lakuncheech, and when he left this anywhere Glooskap was sure to find it, and could tell from its appearance all that had befallen his family. And Martin was called by Glooskap Uch-keen, "my younger brother." The Lord of men and beasts had a belt which gave him magical power and endless strength. And when he lent this to Martin, the younger brother could also do great deeds, such as were only done in old times. Martin lived much with the Mikumwess or Elves, or Fairies, and is said to have been one of them.

Glooscap's Gifts

Four Indians who won to Glooscap's abode found it a place of magical delights; a land fairer than the mind could conceive. Asked by the god what had brought them thither, one replied that his heart was evil and that anger had made him its slave, but that he wished to be meek and pious. The second, a poor man, desired to be rich, and the third, who was of low estate and despised by the folk of his tribe, wished to be universally honored and respected.

The fourth was a vain man, conscious of his good looks, whose appearance was eloquent of conceit. Although he was tall, he had stuffed fur into his moccasins to make him appear still taller, and his wish was that he might become bigger than any man in his tribe and that he might live for ages.

Glooscap drew four small boxes from his medicine bag and gave one to each, desiring that they should not open them until they reached home. When the first three arrived at their respective lodges, each opened his box, and found therein an unguent of great fragrance and richness, with which he rubbed himself.

The wicked man became meek and patient, the poor man speedily grew wealthy, and the despised man became stately and respected. But the conceited man had stopped on his way home in a clearing in the woods and, taking out his box, had anointed himself with the ointment it contained.

His wish was also granted, but not exactly in the manner he expected, for he was changed into a pine tree, the first of the species, and the tallest tree of the forest at that.

Glooscap and the Baby

Glooscap, having conquered the Kewawkqu', a race of giants and magicians, and the Medecolin, who were cunning sorcerers, and Pamola, a wicked spirit of the night, besides hosts of fiends, goblins, cannibals, and witches, felt himself great indeed, and boasted to a certain woman that there was nothing left for him to subdue.

But the woman laughed and said: "Are you quite sure, Master? There is still one who remains unconquered, and nothing can overcome him."

In some surprise, Glooscap inquired the name this mighty individual.

"He is called Wasis," replied the woman, "but I strongly advise you to have no dealings with him."

Wasis was only the baby, who sat on the floor sucking a piece of maple sugar and crooning a little song to himself. Now, Glooscap had never married, and was quite ignorant of how children are managed, but with perfect confidence, he smiled to the baby and asked it to come to him.

The baby smiled back to him, but never moved, whereupon Glooscap imitated the beautiful song of a certain bird. Wasis, however, paid no heed to him, but went on sucking his maple sugar. Glooscap, unaccustomed to such treatment, lashed himself into a furious rage, and in terrible and threatening accents, ordered Wasis to come crawling to him at once.

But Wasis burst into dreadful howling, which quite drowned out the god's thunderous accents and, for all the threatenings of the deity, he would not budge. Glooscap, now thoroughly aroused, brought all his magical resources to his aid. He recited the most terrible spells, the most dreadful incantations. He sang the songs which raise the dead, and which sent the devil scurrying to the nethermost depths of the pit.

But Wasis evidently seemed to think this was all some sort of a game, for he merely smiled wearily and looked a trifle bored. At las, Glooscap, in despair, rushed from the hut, while Wasis, sitting on the floor, fried "Goo-Goo", and crowed triumphantly. And, to this day, the Indians say that when a baby cries "Goo" he remembers the time when he conquered the mighty Glooscap.