The burning of Washington (24 August 1814) by a British force was a pivotal moment in the War of 1812 and in US history. Hoping to pull US military resources away from Canada, the British landed at Chesapeake Bay, defeated an American force at Bladensburg, then pushed on to Washington, D.C., where they burned the Capitol Building and White House.

Background

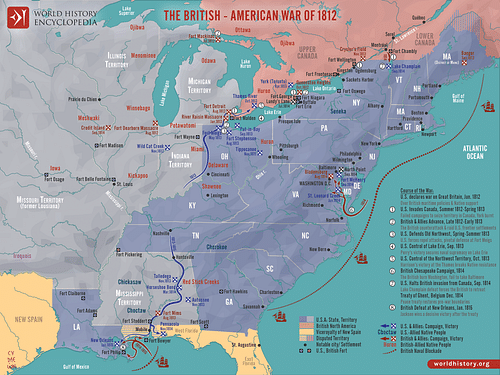

In the summer of 1814, the British-American War of 1812 entered its third year with no satisfactory end in sight. The war had begun as a dispute over the Royal Navy's impressment of American sailors on the high seas, as well as over Britain's support for a burgeoning confederacy of Native American nations hostile to the United States. But by now, circumstances had rendered both of these issues more or less irrelevant; the British had rescinded their 'Orders in Council' that allowed for the capture of US merchant ships, while Tecumseh, the leader of the Native American confederacy, had been killed, ending all hopes for an independent, Anglo-backed Native American state. Despite this, the conflict dragged aimlessly on. As diplomats slowly gathered in the Flemish town of Ghent (in modern Belgium) for peace talks, a US army crossed over into Canada, leading to some of the bloodiest fighting of the war at the Battle of Lundy's Lane (25 July 1814) and the Siege of Fort Erie (4 August to 21 September 1814).

The British were eager to divert American attention away from Canada by striking somewhere on US soil, and for the first time in the war, they had the manpower to do it. In the previous two years, the British and Canadians had been forced to remain on the defensive, since the bulk of Britain's military resources were bogged down in Europe, fighting the armies of Napoleon Bonaparte. But in April 1814, Napoleon finally abdicated and was exiled to the island of Elba, freeing up thousands of battle-hardened British soldiers to be sent to North America. Many of these soldiers were sent first to Bermuda, where Vice Admiral Alexander Cochrane was putting together an expedition to strike the US coast. His primary objective, of course, was to force the US to pull its army out of Canada, but a secondary goal was to satisfy British national honor by burning a major American city or town. This would be in retaliation for the burning of several public buildings in York (present-day Toronto), the provincial capital of Upper Canada, by American troops after the Battle of York (27 April 1813). Though the Americans claimed these fires were accidental, they certainly had many other sins to answer for, as American soldiers had also torched the Canadian frontier towns of Newark, Port Dover, and St. Davids.

After consulting with his subordinate, Rear Admiral George Cockburn, Cochrane decided to land at Chesapeake Bay and target the cities of Washington, D.C., and Baltimore, Maryland. The first was chosen because it was relatively defenseless and because the fall of the US capital was expected to have a major psychological impact on American citizens. The second was chosen because Baltimore was a major trade hub and was also where many of the American warships were built. Cockburn, who had spent the previous months raiding the Chesapeake region, knew the area well and provided Cochrane with the necessary information. When all was ready, the British set sail and arrived in Chesapeake Bay in mid-August.

British Invasion of Maryland

On 19 August 1814, 4,500 British regulars landed at Benedict, Maryland. The villagers had already evacuated the town, leaving no one to greet the redcoats as they piled out of their transports. Veterans of the bloody Peninsular War (1807-1814), these soldiers had spent over three months at sea, leaving many of them sick, fatigued, and in an overall weakened condition. To make matters worse, they were supported by only three small field guns and had no cavalry at all. Still, the soldiers' morale was heightened by their beloved commanding officer, the 47-year-old Major General Robert Ross. Regarded as one of the Duke of Wellington's best generals, Ross had won the love and respect of his men during the war in Spain. Now, as he galloped beside the infantry column, the general was loudly cheered by his men, who knew he would lead them to glory. But as the British soldiers continued their march, they soon realized they would need more than dreams of glory to see them through this campaign. Though they strangely met no Yankee resistance, the weakened British troops soon fell victim to the scorching Maryland summer. Their heavy equipment and uniforms were soon too much to bear, and several men collapsed from heat exhaustion, left behind in the dust.

As they traversed the unfamiliar Maryland countryside, the redcoats were watched by at least one pair of American eyes. Lacking any effective intelligence system, US Secretary of State James Monroe had ridden out himself, to report enemy movements to the president. He watched from a safe distance as the red line of troops wound its way down the road, reporting back that "the general idea also is that Washington is their object, but of this I can form no opinion at this time" (Feldman, 579). It was possible, Monroe wrote, that Georgetown or Alexandria might be their true targets, though Washington seemed most likely. This was grave information for Brigadier General William H. Winder, the Baltimore attorney tasked with the defense of the capital. At this time, Winder had only 6,000 men, a far cry from the 15,000 he had been promised; what was worse, most of these were untrained militia, called into service less than two months before. On 21 August, Monroe reported that the British were in the town of Nottingham – it was here that the secretary-turned-scout noticed a second detachment of British troops moving up the Potomac River on barges. Indeed, as Ross' troops marched overland, Cockburn was supporting him on the riverside, constituting a two-pronged attack.

On the evening of 23 August, Ross' tired troops reached the town of Upper Marlboro, Maryland, where they set up camp for the night. After conferring with Cockburn, Ross decided to make the final push toward Washington the next morning, hoping to throw off the Americans by taking the longer route, through the village of Bladensburg. So it was that, on the sweltering morning of 24 August 1814, the British marched 14 grueling miles (22 km) before reaching Bladensburg shortly after noon. As they approached the single bridge over the Potomac, they could just make out the American militia troops, drawn up in a line of battle; one British lieutenant was shocked that the American troops, wearing hunting jackets or frocks instead of uniforms, looked like simple 'country people' (Berton, 753). The commander of the first British brigade to arrive, Colonel William Thornton, was also unimpressed by the American troops and decided to attack without waiting for the rest of the army to come up.

Battle of Bladensburg

General Winder had about 7,000 men, only 1,000 of whom were regulars of the US Army. They were deployed in two rough lines: the sharpshooters and artillery were out front, with the regiments of Maryland militia behind. These dispositions were largely the work of Secretary Monroe, who had all but taken command of the army from Winder. Indeed, by noon, nearly the entire presidential cabinet had arrived on the heights above Bladensburg to witness the battle, including President James Madison himself; the president, short and pale, looked quite out of place on a battlefield, even with the two dueling pistols hanging from his waist. The president and his cabinet, therefore, were there when Colonel Thornton's brigade of British troops began marching across the bridge, fifes and drums sounding in the distance. Suddenly, the American cannons opened fire, cutting down several British soldiers; the disciplined veterans of Wellington's army, however, kept on coming. Thornton's men made it across the bridge and drove back the forward line of American sharpshooters, only to be halted by the second line of Marylanders. With a shout, the Marylanders surged forward, driving the British back to the riverside, killing or wounding nearly every British officer in the process.

By then, Ross had come up with the rest of his army. He wasted no time setting up his Congreve rockets, which had recently been taken off one of Cockburn's ships. These rockets, as historian Pierre Berton explains, were "long tubes filled with powder, [operating] on the same principle as a Fourth of July firework" (758). Inaccurate though they were, they let out a terrible whistling scream when fired and served to instill panic into the American troops who had never seen anything like them. The Maryland regiments, terrified by the sight of the rockets bursting in the air, broke and fled, allowing the British to stream across the bridge. The retreat turned into a rout, as militiamen threw down their weapons and ran down the road to Washington. President Madison and his cabinet narrowly escaped, making it to the safety of the small town of Brookeville, Maryland. The Battle of Bladensburg resulted in around 64 dead and 185 wounded for the British, while the Americans lost around 26 killed, 51 wounded, and about 100 captured. The battle, which would be referred to by contemporaries as "the greatest disgrace ever dealt to American arms" (Howe, 64) had resulted in a British victory – and left the road to Washington wide open.

Burning of the Capital

Even before the echoes of the guns of Bladensburg could be heard in Washington, civilians were already rushing to evacuate the capital; many were less fearful of the British troops than they were about a potential slave revolt that the capture of the city might spark. As coaches and foot traffic clogged the roads, First Lady Dolley Madison opted to remain in the President's House (as the White House was then known) until she heard word from her husband. With Congress away from the city on its summer recess, and the president and his cabinet on the battlefield, Dolley Madison remained the most visible symbol of federal authority left in the city and knew she had to remain strong. It was only at 3 p.m., when she received a letter from President Madison instructing her to leave, that she decided to evacuate. But even then, she spent precious time removing valuables from the President's House, which famously included the Gilbert Stuart portrait of George Washington, which she took down with the help of her servants. Only then did Dolley Madison climb into her carriage and drive out of the city.

The British troops arrived shortly thereafter, General Ross and Admiral Cockburn riding triumphantly at their head. No sooner had they entered the city than they were fired at by someone in a large brick house to their right; the shooter succeeded in hitting four soldiers, one fatally, before the British succeeded in beating down the door. The soldiers then took aim at the building with their Congreve rockets and blew it up, around the same time that American demolitionists were setting fire to the navy yard to keep it out of enemy hands. The burning of Washington had begun. The British soldiers next made their way to the still-unfinished Capitol Building, which they attacked with axes, chopping up frames, shutters, and doors. Having broken into the building, the soldiers entered the chamber of the House of Representatives, where they piled up everything flammable including desks, papers, and tables. The resulting bonfire was so hot that "glass melts, stone cracks, columns are peeled of their skin, marble is burned to lime" (Berton, 761). With the Capitol Building aflame, the British soldiers moved on to the Treasury building, setting that on fire too before making their way to the abandoned President's House.

Here, they found a table set for 40, clearly in expectation of an American victory at Bladensburg. Laughing, the officers paused to treat themselves to the president's dinner, raising a toast to 'Jemmy's health', as Admiral Cockburn mockingly referred to Madison. Afterward, the President's House was also torched. That evening, a sudden rainstorm quenched the flames, preventing them from spreading to other parts of the city. But the British were not quite finished. More public buildings were set on fire, as Cockburn made his way to the printing offices of the National Intelligencer. The admiral had a personal score to settle, as the Intelligencer had often ridiculed him and his raids in their paper; in retaliation, Cockburn ordered his men to destroy all their 'C' type so that "the rascals can have no further means of abusing my name" (Berton, 762). General Ross, for his part, seemed embarrassed about his role in the fires of the previous night, especially regretting letting the Capitol library burn. Nor would he have allowed the President's House to burn down if Dolley Madison had stayed behind, telling one local that he "make[s] war neither against letters nor ladies" (ibid).

In the meantime, the storm worsened and eventually spawned a tornado that tore through the city, adding to the damage. At one point, the tornado picked up and flung two cannons, killing and injuring British soldiers and American civilians. It was around this time that Cockburn and Ross decided to leave; they had come not to occupy the capital, after all, but only to burn it, and now needed to make their way to their second target of Baltimore. Thus, after only 26 hours of occupation, the British were gone, leaving a charred and ruined city in their wake.

Aftermath

Much like the occupation of Philadelphia during the American Revolution, the capture of Washington did not have the demoralizing psychological impact the British had been counting on. In fact, it only rallied the local population against the British invaders. After leaving Washington, the British advanced to Baltimore, but were unable to take the city due to the spirited defense of the American garrison in Fort McHenry; the British bombardment of the fort on the night of 13 September inspired an onlooker, lawyer Francis Scott Key, to write the Star Spangled Banner. The British failure to take Baltimore was coupled with the death of General Ross, who was killed by an American sharpshooter early in the battle. Demoralized, yet having completed much of their mission, the British piled back on their ships and left the Chesapeake.

In the immediate aftermath of the capture of Washington, lawlessness reigned supreme as people began to loot the abandoned buildings; one newspaper, disgusted by this behavior, referred to the looters as "knavish wretches about the town who profited from the general distress" (Howe, 65). Gradually, however, the Madison administration returned to the capital, with the president taking up residence in the Octagon House while the President's House and the other public buildings were being rebuilt. Looking for someone to blame for the disaster, Madison and his allies accused Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr. of dismissing the possibility of a British attack on the capital and of not readying the city's defenses; after receiving Armstrong's resignation, Madison entrusted Monroe with the War Department in addition to his existing duties as secretary of state. In early 1815, a proposal to move the capital back to Philadelphia was defeated in Congress, and work commenced on rebuilding Washington, D.C. This would prove to be a long process that would last well into Monroe's presidential administration, but it would eventually be completed. The rebuilt White House and Capitol Building would cover the scars of the War of 1812, a conflict that had become particularly pointless by the time it reached the US capital.