Manabozho tales are the stories of the trickster figure and culture hero of the Ojibwe (Ojibway/Chippewa) and other Algonquin Native American nations of present-day northern United States and southeast Canada. Manabozho is a supernatural entity, often depicted with god-like powers, but is not a god, even though, in some stories, he is featured as the co-creator.

According to Ojibwe lore (as well as that of the other Algonquin people), Manabozho (also given as Nanabozho) is a Spirit Being sent to earth by the Great Spirit (Gitchee Manidoo or Gitche Manitou) to teach animals, and then people, the right way to live. He sometimes does so directly, through instruction, other times through punishment, or, as he is a shapeshifter, through trickery and deceit.

As with the trickster stories of other Native peoples of North America – the Wihio tales of the Cheyenne, Iktomi tales of the Sioux, Coyote tales of the Shasta nation, Glooscap tales of the Wabanaki Confederacy, and many others – Manabozho appears sometimes as a wise man, sometimes as a fool, can appear as a hero, or as a villain, or even act like a petulant and petty child. Manabozho tales, like those of the other nations, always feature some form of transformation.

He sometimes appears as a man but is often depicted as a large rabbit and, in this form, is known as Mishaabooz ("Great Rabbit"). He may appear in any form he likes, however, whether a leaf or a stump (a form he favors in several tales) or anything else. He is credited by the Ojibwe, and other Algonquin people, with co-creating the earth (or, in some versions, dry land after a great flood), naming all the plants and animals, giving people the spiritual precepts of their religion (Midewiwin, "the way of the heart") teaching the people to fish, and inventing the characters of the Ojibwe written language, part of the Algonquian language family.

Ojibwe Culture & History

The Ojibwe are Algonquin people, related culturally, ethnically, and linguistically to others of the region of southeast Canada and the northern United States, and are members of the Council of the Three Fires, which also includes the Odawa and Potawatomi nations. The meaning of their name continues to be debated, but one possibility is suggested by scholar Adele Nozedar, who suggests it "means 'to roast until puckered' or 'puckered moccasin people' and refers to the puckered seams of the moccasins the Ojibwe wore" (337). The other name they are known by, Chippewa, began as a mispronunciation of Ojibwe, though both names became used by the people to refer to themselves.

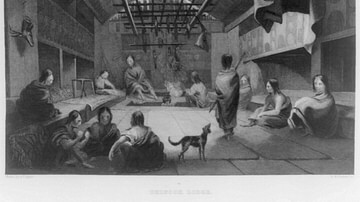

The Ojibwe, like other Native American nations, claim they originated from the earth and, in their case, at the mouth of the waterway now known as the Saint Lawrence River in modern-day Quebec. They were at first a hunter-gatherer society until the establishment of permanent settlements of homes known as wigwams, usually made of birch bark over bent saplings and woven reeds (wiigiwaam in the Anishinaabe Algonquin language of the Ojibwe). Men built the wigwam and women were responsible for furnishing it.

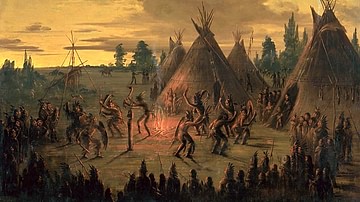

As with other Native American nations, the men hunted, fished, protected the village, and made war while the women maintained the home, cooked the food, raised the children, tended to the crops, and engaged in trade with other communities. Their spiritual/religious belief, Midewiwin, emphasizes the importance of balance within oneself, between the human community and the natural world, and working to heal rifts when they occur. Midewiwin ceremonies focus on the relationship between the individual and the spirit world to encourage respect for the environment and other people. Although still practiced, Midewiwin adherents declined after the arrival of Europeans and the spread of Christianity.

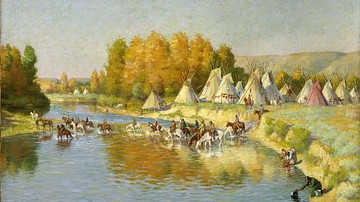

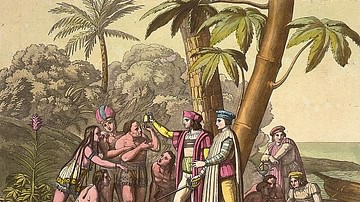

The Ojibwe first encountered Europeans through contact with French missionaries in 1640, established friendly relations with French fur traders, and acquired firearms and iron weapons from them which they used to drive the Lakota Sioux from the region and down onto the Great Plains. They sided with the French against the British during the French and Indian War (1754-1763), with the British against the Continentals during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783), and with the British against the United States in the War of 1812. After that conflict, the United States attempted to forcibly relocate the Ojibwe west of the Mississippi River, but Chief Kechewaishke ("Great Buffalo", l. c. 1759-1855) negotiated settlement for the Ojibwe on reservations of their ancestral lands near Lake Superior.

The Ojibwe culture and language was adversely affected owing to the occupation of their lands by French, English, and Euro-American nations, but has survived, and the Ojibwe still live, more or less, along with the other Algonquin people, in the areas they occupied thousands of years ago. The language is still spoken and is used to tell the traditional tales like the three below.

Text

The following tales are taken from Native American Myths & Legends (2023), edited by J. K. Jackson (A Legend of Manabozho and Manabozho and His Toe) and from Manabozho, the Great White Rabbit and Other Indian Stories (1918, republished in 2024) by Maude Radford Warren (The Story of the Hopper).

A Legend of Manabozho

Manabozho made the land. The occasion of his doing so was this.

One day he went out hunting with two wolves. After the first day's hunt one of the wolves left him and went to the left, but the other continuing with Manabozho he adopted him for his son. The lakes were in those days peopled by spirits with whom Manabozho and his son went to war. They destroyed all the spirits in one lake, and then went on hunting. They were not, however, very successful, for every deer the wolf chased fled to another of the lakes and escaped from them. It chanced that, one day, Manabozho started a deer, and the wolf gave chase. The animal fled to the lake, which was covered with ice, and the wolf pursued it. At the moment when the wolf had come up to the prey, the ice broke, and both fell in, when the spirits, catching them, at once devoured them.

Manabozho went up and down the lakeshore weeping and lamenting. While he was thus distressed, he heard a voice proceeding from the depths of the lake.

"Manabozho," cried the voice, "why do you weep?"

Manabozho answered–

"Have I not cause to do so? I have lost my son, who has sunk in the waters of the lake."

"You will never see him more," replied the voice; "the spirits have eaten him."

Then Manabozho wept the more when he heard this sad news.

"Would," said he, "I might meet those who have thus cruelly treated me in eating my son. They should feel the power of Manabozho, who would be revenged."

The voice informed him that he might meet the spirits by repairing to a certain place, to which the spirits would come to sun themselves. Manabozho went there accordingly, and, concealing himself, saw the spirits, who appeared in all manner of forms, as snakes, bears, and other things. Manabozho, however, did not escape the notice of one of the two chiefs of the spirits, and one of the band, who wore the shape of a very large snake, was sent by them to examine what the strange object was.

Manabozho saw the spirit coming and assumed the appearance of a stump. The snake coming up wrapped itself around the trunk and squeezed it with all its strength, so that Manabozho was on the point of crying out when the snake uncoiled itself. The relief was, however, only for a moment. Again, the snake wound itself around him and gave him this time even a more severe hug than before. Manabozho restrained himself and did not suffer a cry to escape him, and the snake, now satisfied that the stump was what it appeared to be, glided off to its companions. The chiefs of the spirits were not, however, satisfied, so they sent a bear to try what he could make of the stump. The bear came up to Manabozho and hugged, and bit, and clawed him till he could hardly forbear screaming with the pain it caused him. The thought of his son and of the vengeance he wished to take on the spirits, however, restrained him, and the bear at last retreated to its fellows.

"It is nothing," it said; "it is really a stump."

Then the spirits were reassured, and, having sunned themselves, lay down and went to sleep. Seeing this, Manabozho assumed his natural shape, and stealing upon them with his bow and arrows, slew the chiefs of the spirits. In doing this he awoke the others, who, seeing their chiefs dead, turned upon Manabozho, who fled. Then the spirits pursued him in the shape of a vast flood of water. Hearing it behind him the fugitive ran as fast as he could to the hills, but each one became gradually submerged, so that Manabozho was at last driven to the top of the highest mountain. Here the waters still surrounding him and gathering in height, Manabozho climbed the highest pine-tree he could find. The waters still rose. Then Manabozho prayed that the tree would grow, and it did so. Still the waters rose. Manabozho prayed again that the tree would grow, and it did so, but not so much as before. Still the waters rose, and Manabozho was up to his chin in the flood, when he prayed again, and the tree grew, but less than on either of the former occasions. Manabozho looked round on the waters and saw many animals swimming about seeking land. Amongst them he saw a beaver, an otter, and a muskrat. Then he cried to them, saying–

"My brothers, come to me. We must have some earth, or we shall all die."

So, they came to him and consulted as to what had best be done, and it was agreed that they should dive down and see if they could not bring up some of the earth from below.

The beaver dived first, but was drowned before he reached the bottom. Then the otter went. He came within sight of the earth, but then his senses failed him before he could get a bite of it. The muskrat followed. He sank to the bottom and bit the earth. Then he lost his senses and came floating up to the top of the water. Manabozho awaited the reappearance of the three, and, as they came up to the surface, he drew them to him. He examined their claws but found nothing. Then he looked in their mouths and found the beaver's and the otter's empty. In the muskrat's, however, he found a little earth. This Manabozho took in his hands and rubbed till it was a fine dust. Then he dried it in the sun, and, when it was quite light, he blew it all round him over the water, and the dry land appeared.

Thus, Manabozho made the land.

The Story of the Hopper

The animals roamed wherever they pleased over the land. They wandered through the forests and climbed the mountains. They went into all the caves except one. The one Manabozho told them not to enter.

"What is inside, Manabozho?" asked the animals.

"I do not mind telling you, my children," said Manabozho. "It is a kind of weed called tobacco. Tobacco is not good for you. I do not want any of you ever to touch it."

All the animals trusted Manabozho and obeyed him, except one. He was a great animal, all green and black, called the Hopper. His eyes were bright and keen. He had silky wings and fine, long legs. It pleased him to jump farther than any of the other animals. He began to think he was larger than any of them.

One day, he said to himself: "Of course, none of the other animals should touch the tobacco. But I ought to because I am so great. I want to see what this weed looks like."

So, he hopped up and down before the cave. The entrance was not hidden in any way, for Manabozho trusted to the honor of his animals.

"I know I am disloyal," said the Hopper. "I know that I ought not to disobey Manabozho. But it is not as wrong in me to do this as if I were a little animal. How great I am! By rights, I ought to be a ruler with Manabozho."

He made a good many reasons for disobeying Manabozho. And, at last, he went into the mouth of the cave. It was dark inside and, at first, he could see nothing. After a while, he saw that the place was full of piles of brown, strong-smelling leaves. The Hopper went closer and closer. At last, he snatched a mouthful of them.

At that moment, he heard a noise like thunder. It was the voice of Manabozho, who was running down the hill toward the cavern.

"Disobedient Hopper!" cried Manabozho. "Did you think I did not know what you are doing? Run! Run! I am following to punish you."

The Hopper rushed out of the cavern and began to make great leaps through the forest. At first, he jumped over the trees, then only as high as the lower branches. He saw that he was growing smaller and smaller.

"Manabozho! Manabozho!" he cried. "Do not make me little, I beg you! I was so happy when I was large. I am punished enough. Manabozho, forgive me."

"I forgive you," said Manabozho. "But you must pay for your disobedience."

The poor Hopper was now no larger than a bird.

"Oh, good Manabozho, stop!" he cried. "I am no larger than a sparrow."

"You shall never leap higher than the grass," said Manabozho.

And, at that moment, the disobedient creature turned into the animal we know as the grasshopper.

"You may keep the mouthful of tobacco for which you have paid so dearly," said Manabozho. "But you must always give it up when you are asked for it. Sometime in the future, there will be little children on the earth. They will catch you and say, 'Grasshopper, grasshopper, give me tobacco.' Then you must obey."

The poor Grasshopper felt very sad. There he stood, with the brown tobacco juice on his mouth, and trembled as Manabozho spoke.

"Moreover," went on Manabozho. "You shall never help mankind. You will always be more or less harmful to crops. I can think of no punishment worse than that of being useless."

Manabozho and His Toe

Manabozho was so powerful that he began to think there was nothing he could not do. Very wonderful were many of his feats and he grew more conceited day by day. Now, it chanced that, one day, he was walking about amusing himself by exercising his extraordinary powers, and at length he came to an encampment where one of the first things he noticed was a child lying in the sunshine, curled up with its toe in its mouth.

Manabozho looked at the child for some time and wondered at its extraordinary posture.

"I have never seen a child before lie like that," he said to himself. "But I could lie like that."

So saying, he put himself down beside the child and, taking his right foot in his hand, drew it towards his mouth. When he had brought it as near as he could, it was yet a considerable distance away from his lips.

"I will try the left foot," said Manabozho.

He did so, and found that he was no better off, neither of his feet could he get to his mouth. He curled and twisted and bent his large limbs and gnashed his teeth in rage to find that he could not get his toe to his mouth. All, however, was in vain.

At length, he rose, worn out with his exertions and passion, and walked slowly away in a very ill humor, which was not lessened by the sound of the child's laughter, for Manabozho's efforts had awakened it.

"Ah, ah!" said Manabozho. "Shall I be mocked by a child?"

He did not, however, revenge himself on his victor but, on his way homeward, meeting a boy who did not treat him with proper respect, he transformed him into a cedar tree.

"At least," said Manabozho, "I can do something."