The Dade Massacre (also given as the Dade Battle, 28 December 1835) was the opening engagement of the Second Seminole War (1835-1842) between Euro-American forces and those of the Seminole, Black Seminole, and runaway slaves who had found freedom among the Native Americans of Florida. Of the 110 men of Dade's command, 108 were killed.

Major Francis L. Dade (l. 1792-1835) was ordered by General Duncan Lamont Clinch (l. 1787-1849) to march his men from Fort Brooke to reinforce the garrison at Fort King and chose a slave named Louis Pacheco, owned by one Antonio Pacheco of a nearby plantation, as his guide. Louis, who secretly had close ties to the Exiles (runaway slaves from the Carolinas, Georgia, and other slave-holding states), Black Seminoles, and Seminoles, alerted them to the route Dade would take to Fort King and suggested the perfect place for an ambush.

Louis' plan worked as envisioned and almost the entire command, including Dade, was killed in the attack. The casualties for the Seminole alliance were three killed and five wounded. The Dade Massacre and the ensuing Second Seminole War were a direct result of the Indian Removal Act of 1830 and the common practice of slave-hunters from the United States kidnapping former slaves, Black Seminoles, and freedmen for enslavement on US plantations.

There was no formal victory declared at the end of the Second Seminole War, and no treaties were signed. Many of the Seminole, Black Seminole, and former slaves were able to negotiate relocation to Indian Territory (modern-day Oklahoma), while others were forcibly removed, and still others never surrendered and remained in Florida.

One of the most detailed accounts of the Dade Massacre comes from the famous abolitionist Joshua Reed Giddings (l. 1795-1864) of the US House of Representatives in his book The Exiles of Florida: or, The Crimes Committed by Our Government against the Maroons, who Fled from South Carolina and other Slave States, Seeking Protection under Spanish Laws, published in 1858. Giddings' account is based on an earlier history of Florida, which drew on interviews with members of the Seminole forces that ambushed Dade in December 1835.

Spanish Florida, Tensions, & Second Seminole War

The region that became Florida was claimed by the Spanish after Juan Ponce de León landed there in April 1513. Between 1539 and 1559, Spanish settlements developed, displacing the indigenous peoples who included the Creek and the Pensacola nations, but trade was established, and Spaniards married Native Americans of various nations, and, in time, also former slaves who had escaped from bondage in the Thirteen Colonies.

In 1738, Fort Mose, near St. Augustine, was established and garrisoned by escaped slaves who were granted freedom and citizenship in exchange for their defense of the region against encroachments by the British colonists to the north. Fort Mose became the first legally recognized free Black settlement in North America.

Spain encouraged slaves in the Thirteen Colonies to flee to Florida, and many did so, along with an influx of Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee Creek, and Yamasee citizens, some of whom broke off from the larger Creek bands to settle on their own, and these became known as the Seminole, whose name may be derived from the Creek for "runaway" or "outcast." Some Seminole intermarried with former slaves and established their own communities of Black Seminoles. These various groups lived and traded with each other until Spain lost Florida to the British in 1763 after the French and Indian War (1754-1763). The British then established themselves in the region and encouraged their citizens to settle there.

The Seminole sided with the British during the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) and, afterwards, Spain was able to retake Florida, and it became a haven for runaway slaves and Native Americans fleeing Euro-American persecution. General Andrew Jackson led troops into Florida to break up these enclaves of African Americans and Native Americans in the First Seminole War (1816-1819). After Jackson became President of the United States, he issued the Indian Removal Act of 1830 to forcibly relocate the Seminole (as well as many other Native peoples of North America) to Indian Territory west of the Mississippi River. Pressure on the Seminole to comply with this led to the Second Seminole War, which also encouraged one of the largest slave uprisings in US history as the Seminole resistance inspired slaves on plantations in the Carolinas and Georgia to fire the fields and flee to Florida.

The event that set the Second Seminole War in motion (though not the cause of the conflict) was the Dade Massacre of 1835. To the Seminole, Black Seminole, and free Blacks of Florida, the Dade Massacre was a great victory, and leaders like Chief Osceola of the Seminole (l. 1804-1838) and John Horse of the Black Seminole (also known as Jean Caballao, l. c. 1812-1882) looked forward to many more. To the US authorities, however, the Dade Massacre was simply proof that the Native Americans had to be removed from Florida along with any of their allies. Osceola died in captivity in 1838, but John Horse was able to lead his people to Oklahoma and then, when US authorities refused to honor their agreement, on to Mexico.

Giddings' Account

Giddings' account details the motivation of people like Louis Pacheco, the Seminole, Black Seminole, and the exiles from the United States who had either been held in bondage or came from families that had fled to Florida years before. The Seminole and their allies were fighting for the freedom to live where they wanted in the way they had grown accustomed to, essentially the same principles of "life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness" the United States claimed as inalienable rights for its citizens.

Giddings, as the title of his book clearly suggests, felt the United States had wronged the Native Americans and African Americans of Florida and, as a staunch abolitionist, was quite vocal with his views, whether in print, public speeches, or among his colleagues in the House of Representatives. His views were extremely unpopular among slave-holding states, and, in 1861, a bounty of $10,000.00 was offered through a Virginia newspaper for his capture. In part to prevent this, President Lincoln sent Giddings to Canada as consul general, where he died, of natural causes, in 1864.

Text

The following passage is taken from The Exiles of Florida: or, The Crimes Committed by Our Government Against the Maroons, who Fled from South Carolina and Other Slaves, Seeking Protection Under Spanish Laws (1858) by Joshua R. Giddings, pp. 101-106, republished in 2022 by Legare Street Press.

General Clinch had foreseen that hostilities were unavoidable, and, as early as the fifteenth of November, had sought to increase the number of troops at Fort King by such reinforcements as could be spared from other stations. For this purpose, he ordered Major Dade, then at Fort Brooke, near Tampa Bay, to prepare his command for a march to Fort King. The distance was one hundred and thirty miles, through an unsettled forest, much diversified with swamps, lakes, and hommocks. No officer nor soldier could be found who was acquainted with the route, and a guide was indispensable: yet men competent to the discharge of so important a trust were rarely to be found, for the lives of the regiment might depend upon the intelligence and fidelity of their conductor.

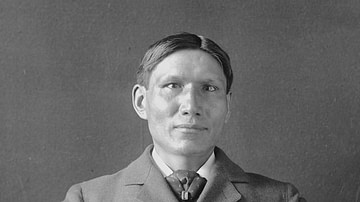

At this point in our history, even before the commencement of general hostilities, we are led to the acquaintance of one of the most romantic characters who bore part in the stirring scenes of that day. On making inquiry for a suitable guide, the attention of Major Dade was directed to a colored man named Louis. He was the slave of one of the old and respectable Spanish families, named Pacheco, who resided in the vicinity of Fort Brooke.

Major Dade applied to the master, Antonio Pacheco, for information concerning his slave, and was assured that Louis, then near thirty years of age, was one of the most faithful, intelligent, and trustworthy men he had ever known. He had also been well bred, was polite, accomplished, and learned. He read, wrote, and spoke with facility, the Spanish, French, and English languages, and spoke the Indian, and was perfectly familiar with the route to Fort King, having frequently traveled it.

Pleased with the character and appearance of Louis, Major Dade entered into an agreement with the master for his services in conducting the troops through the forest to Fort King, at the rate of twenty-five dollars per month, and stated the time at which the service was to commence. The contract was made in the presence of Louis, who listened attentively to the whole arrangement, to which he, of course, gave his own consent.

Louis Pacheco was too enlightened to smother the better sympathies of the human heart. He was well informed, and understood the efforts that were making to reenslave his brethren, the Exiles. With many of them he had long been acquainted; he had witnessed the persecutions to which they had been subjected, the outrages heaped upon them, and now saw clearly the intention to subject them to slavery…He had spent his own life thus far in servitude, and, although his condition was regarded with envy by the plantation servants around him, he yet sighed for freedom.

Blessed with an intellect of no ordinary mold, he reflected deeply upon his condition and determined upon his course. Hostilities had not yet commenced, and he was in the daily habit of conversing with Indians, and often with Exiles. He was well acquainted with the character of each and knew the men to whom he could communicate important information with safety.

To a few of the Exiles, men of integrity and boldness, he imparted the facts that Dade, with his troops would leave Fort Brooke about the twenty-fifty of December, for Fort King, and that he, Louis, was to act as their guide; that he would conduct them by the trail leading near the Great Wahoo Swamp and pointed out the proper place for an attack.

This information was soon made known to the leading and active Exiles, and to a few of the Seminole chiefs and warriors. The Exiles, conscious that the war was to be waged on their account, were anxious to give their friends some suitable manifestation of their prowess. They desired as many of the Exiles capable of bearing arms as could assemble at a certain point in the Great Wahoo Swamp, to meet them there as early as the twenty-seventy of December, armed, and prepared to commence the war by a proper demonstration of their gallantry.

Information was sent to Osceola and his followers, inviting them to be present. They were lying secreted near Fort King, too intent upon [attack]. However, many other chiefs and warriors assembled at the time and place designated, in order to witness what they supposed would be the first scene in the great drama about to be acted. Their spies detached for that purpose, arrived at their rendezvous almost hourly, bringing information of the commencement of Dade's march, the number of men forming his battalion, and their places of encampment each night.

In the evening of the twenty-seventh, their patrols brought word that Dade and his men had arrived within three miles of the point at which they intended to attack them. Of course, every preparation was now made for placing themselves in ambush at an early hour, along the trail in which it was expected the troops would pass.

The scouts reported that precisely one hundred and ten men constituted the force which they expected to encounter, and the official report fully confirms the accuracy of their intelligence. The Exiles looked to the coming day with great intensity of feeling. More than two hundred years since, their ancestors had been piratically seized in their own country, and forcibly torn from their friends – from the land of their nativity. For a time, they submitted to degrading bondage; but more than a century had elapsed since they fled from South Carolina and found an asylum under Spanish law in the wilds of Florida.

There, their fathers and mothers had been buried. They had often visited their graves and mourned over the sad fate to which their race appeared to be doomed. For fifty years they had been subjected to almost constant persecution at the hands of our government. The blood of their fathers, brothers, and friends, massacred at "Blount's Fort" was yet unavenged. They had seen individuals from among them piratically seized and enslaved. Their friends…had been openly and flagrantly kidnapped, and sold into interminable servitude, where they were then sighing and moaning in degrading bondage.

In looking forward, they read their intended doom, clearly written in the slave codes of Florida and the adjoining States, which could only be avoided by their most determined resistance. If they behaved worthy of men in their condition, their influence with their savage allies would be confirmed, and they would be able to control their action on subsequent occasions. Every consideration, therefore, tended to nerve them to the work of death which lay before them.

In the meantime, their victims were reposing at only four or five miles distant in conscious security. Their encampment had been selected according to military science. The men and officers were encamped in scientific order. Their guards were placed, their patrols sent out, and every precaution taken to prevent surprise. They had seen service, and cheerfully encountered its hardships, privations, and dangers, but had no suspicion of the fate that awaited them on the coming day.

At dawn, the men were paraded, the roll called, and the order for regulating the day's march given. They were then dismissed for breakfast and, at eight o'clock, resumed their march, and proceeded on their way in the full expectation of reaching their destination by the evening of that day.

But the insidious foe had been equally vigilant. They had left their island encampment with the first light of the morning, and each had taken his position along the trail in which the troops were expected to march, but at some thirty or forty yards distant. Each man was hidden by a tree, which was to be his fortress during the expected action. A few rods on the other side of the trail lay a pond of water, whose placid surface reflected the glittering rays of the morning sun. All was peaceful and quiet as the breath of summer.

Unsuspicious of the hidden death which beset their pathway, the troops entered this defile, and passed along until their rear had come within the range of the enemies' rifles, when, at a given signal, each warrior fired, while victim was in full view and unprotected. One half of that ill-fated band, including the gallant Dade, fell at the first fire. The remainder were thrown into disorder. The officers endeavored to rally them into line; but their enemy was unseen, and ere they could return an effective shot, a second discharge from the hidden foe laid one half their remaining force prostrate in death.

The survivors retreated a short distance toward their encampment of the previous night, and, while most of the Exiles and Indians were engaged in scalping the dead and tomahawking those who were disabled, they formed a hasty breastwork of logs for their defense. They were, however, soon invested by the enemy, and the few who had taken shelter behind their rude defenses were overcome and massacred by the Exiles, who conversed with them in English, and then dispatched them.

Only two individuals, beside Louis the guide, made their escape. Their gallant commander, his officers and soldiers, whose hearts had beat high with expectation in the morning, at evening lay prostrate in death; and as they sable victors relaxed from their bloody work, they congratulated each other on having revenged the death of those who, twenty years previously, had fallen at the massacre of "Blount's Fort." The loss of the allied forces [of Exiles and Indians] was three killed and five wounded.

After burying their own dead, they returned to the island in the swamp long before nightfall. To this point, they brought the spoils of victory, which were deemed important for carrying on the war. Night had scarcely closed around them, however, when Osceola and his followers arrived from Fort King, bringing intelligence of the deaths [of those they had attacked there]. There, too, was Louis, the guide to Dade's command. He was now free! He engaged in conversation with his sable friends. Well-knowing the time and place at which the attack was to be made, he had professed necessity for stopping by the wayside before entering the defile; thus, separating himself from the troops and danger. Soon as the first fire showed him the precise position of his friends, he joined them; and swearing eternal hostility to all who enslave their fellow men, lent his own efforts in carrying forward the work of death, until the last individual of that doomed regiment sunk beneath their tomahawks.

The massacre of the unfortunate Dade and his companions, and the murder of Thompson and his friends at Fort King, occurred on the same day, and constituted the opening scenes of the Second Seminole War.