The iconic image of Kokopelli, the flute-playing kachina spirit of the Pueblo peoples, specifically the Hopi, is easily the most recognizable figure from Native American culture in the Southwest United States but, according to traditional Native understanding, the Flute Player and Kokopelli are two different entities.

Kokopelli (also given as Kokopolo, Kokopele, Ololowishkya, Neopkwai'i) is a kachina (spirit figure) of the Pueblo peoples, associated closely with the Hohokam and Hopi (among others) and is regarded by the Hopi as a fertility spirit (or fertility god), represented as a hump-backed man with an erect phallus, beak, and bird feathers on his head. He is understood as a separate entity from the Flute Player figure, who is known either as maahu ("the cicada") or as lelenhoya ("flute player"). Among the Zuni, the most famous Flute Player is Paiyatuma (also given as Paiyatamu) – "The God of Dew and of the Dawn" – who first gave the Zuni the gift of the flute and "new music" as related in the legend of The Four Flutes.

At some point, non-Natives conflated the image of Paiyatuma the Flute Player (or another kachina flute player) and/or the cicada flute player, with Kokopelli, agent of fertility and, like Paiyatuma, a trickster figure who can appear as a clown, or a sage, a god, or a fool. Kokopelli and Paiyatuma even appear together in some depictions of Pueblo peoples' religious ceremonies, clearly suggesting they are two separate entities: one, the hump-backed agent of fertility, the other, the flute player. Confusion of the one with the other is encouraged by petroglyphs depicting a hump-backed flute player, but, according to the traditional understanding of the Pueblo peoples, the flute player is not Kokopelli.

Pueblo Peoples

The term "Pueblo peoples" does not refer to a single Native American nation but to those nations who historically lived in pueblos, including, though not limited to the Acoma, Hohokam, Hopi, Navajo, Tewa, Zia, and Zuni. Pueblo is Spanish for "village", and the people came to be known by the Spanish as Puebloans. They were initially a hunter-gatherer society until they took up agriculture, especially the cultivation of maize (corn) at some point c. 2000 BCE, when they also initiated irrigation techniques, later mastered by the Hohokam, who created the largest irrigation system in North America. The canals built by the ancient Hohokam can still be seen in modern-day Arizona and some are still in use.

At first, the people lived in caves or built structures protruding from cliffs but eventually shifted to buildings made of wood and adobe with multiple rooms within each structure, often accessed by ladders on the sides of the building with an entrance toward or at the top, as a means of defense. The Pueblo peoples had a highly developed civilization at the time the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, at which time many were killed, died of European diseases, or were enslaved, notably after the Acoma Massacre of 1599, and their religious practices were outlawed by c. 1665. The kachina dolls, kachina masks, and prayer sticks of the people were burned, and Kachina Dances forbidden in an effort to "stamp out sorcery" by the Christian missionaries.

These abuses, as well as a drought that brought famine, and raids by Apache bands seeking food, finally led to the Pueblo Revolt of 1680 (also known as Pope's Rebellion/Po'pay's Rebellion) led by the Tewa medicine man Po'pay (l. c. 1630 to c. 1692), which killed 400 Spaniards and drove the others from the region for the next twelve years. The revolt also released the Spaniards' horses, which were later taken by citizens of the Plains Indians, contributing to the so-called horse culture of the Great Plains.

Kachina Spirits & Ceremonies

Although the prohibition of their religious practices was not the only reason for the Pueblo Revolt, it was certainly a contributing factor as the Pueblo peoples historically understood the world as inhabited by kachina spirits who needed to be recognized and respected. Scholar Adele Nozedar defines the kachina:

This word [Kachina] derives from ka (respect) and china (spirit). The kachina is a powerful example of how, for Native Americans, the world of human beings, the world of nature, and the world of spirit are all intertwined. Grasping this concept is essential to any true understanding of the Native American psyche. The concept of the kachina belongs in particular to the Pueblo people. Frank Waters, in his 1963 publication, The Book of the Hopi, tells us:

The kachinas, then, are the inner forms, the spiritual components, of the outer physical forms of life, which may be invoked to manifest their benign powers so that one may be enabled to continue the never-ending journey. They are invisible forces of life – not gods, but rather intermediaries, messengers. Hence, their chief function is to bring rain, insuring the abundance of crops and the continuation of life.

(235)

The kachinas are also sometimes understood as the spirits of one's ancestors, who divide their time between the spirit world and their relatives' villages. They may bring messages from the higher realms, protect one from evil spirits that bring disease or bad luck, heal sickness, and encourage positivity, creativity, fertility, and spiritual expansion or enlightenment. If disrespected, however, a kachina can also bring sickness, bad luck, and other misfortune. One respects the kachinas through personal and public ceremonies, which made the prohibition of such rituals by the Spanish all the more intolerable.

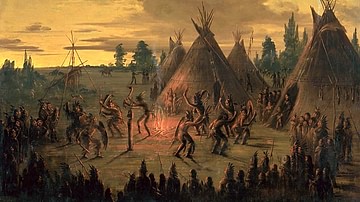

Kachina ceremonies are still observed today by the Pueblo peoples following the same traditions as their ancestors. In putting on a kachina mask and participating in a Kachina Dance, one is understood as channeling that particular spirit; the masked dancer is not just representing the spirit or playing a role but is understood as being inhabited by that spirit throughout the course of the ceremony. In this way, the invisible kachina becomes visible, identifiable, and more closely associated with their specific power or aspect of the natural world. Scholar Larry J. Zimmerman comments:

A kachina expressed a belief that everything has a life force, which humans must interact with. These powerful beings are important in the Hopi and Pueblo culture. There are about 400 figures in total, representing concepts as well as natural phenomena such as the sun, the stars, corn, and insects. In tribal myth, many kachinas taught people the essential skills such as medicine or agriculture.

Traditionally, small kachina dolls were carved out of cottonwood and given as gifts to children by the masked dancers who appeared in the villages during the ceremonies which ran from the winter solstice through July.

(185)

The kachina dolls are given to children to teach them how to identify the kachinas. Each kachina doll was traditionally made by hand, usually by a child's maternal uncle, and looked precisely like the kachina it represented. The manufacture of kachina dolls has become commercialized in the past 200 years, ever since Euro-Americans began prizing them as collectibles, but citizens of the Nations of the Pueblo Peoples still make dolls by hand in accordance with tradition.

Clowns are also an important aspect of the kachina ceremonies as they not only amuse and entertain an audience but take on the role of the sacred clown, a contrarian – associated with the trickster figure – who behaves in unexpected and socially unacceptable ways to break people from rigid thought, belief, expectation, or custom. By enacting lewd or unacceptable behavior in public, these clowns draw an audience's attention to their own behavior, encouraging change and overall transformation, and, in this respect, they are spiritually linked to Kokopelli and Paiyatuma.

Kokopelli & Paiyatuma

Kokopelli and Paiyatuma, powerful kachina spirits who are sometimes depicted presiding over maize ceremonies, are both associated with transformation, fertility, and growth. Kokopelli is said to carry the spirits (or seeds) of unborn children in the pack on his back (or the hump of his back) and, as he passes through a village, to distribute these to young women who then become pregnant. He is also said to carry the seeds of all the plants of the world (or of the world that came before the present) and casts these about to encourage abundant growth of plants, crops, herbs, and flowers.

Paiyatuma is also associated with plant growth and fertility overall, as seen in the legend of Paiyatuma and the Maidens of the Corn in which he brings the Corn Maidens, who make the plants grow, to the people. He is primarily known as the Flute Player, the god of dew and of the dawn. Both he and Kokopelli are understood as trickster figures, and both sometimes appear as a sacred clown. In Paiyatuma and the Maidens of the Corn, for example, Paiyatuma appears before the Council as a clown in dirty clothes, making jokes, before allaying their concerns about the seemingly missing Corn Maidens.

As tricksters, both Kokopelli and Paiyatuma encourage transformation and new ways of thinking or looking at oneself, one's behavior, and any given circumstances of life. Kokopelli and his female consort Kokopelmana (also given as Kokopelmimi) are often depicted acting inappropriately in public – like the clowns in the kachina ceremonies – encouraging an audience to question what it means to behave appropriately, what the value of such behavior might be, and how they have been behaving themselves.

Petroglyphs throughout the Southwest United States, down through Central and South America, and up into modern-day Canada depict a hump-backed flute player who has come to be identified as Kokopelli, but the original Kokopelli of the lore of the Pueblo peoples never played the flute, and so this figure must be representing someone else, possibly Paiyatuma, possibly another flute-playing kachina spirit, possibly an anthropomorphic rendering of the cicada as flute player. Scholar Shannon Burke comments:

Alph Secakuku, the first Hopi to officially comment on this misunderstanding in his 1995 book, unequivocally states: "Kokopolo is a katsina with a hump—back. He is not a Flute player, though he has been mistakenly referred to as such."

(1)

Many modern Kokopelli tales and descriptions of the entity claim he plays his flute to drive away winter and usher in the spring but, as Paiyatuma is known as the god of dew and of the dawn – of new beginnings – he is more likely to have this responsibility. The figure in some petroglyphs is depicted with an erect phallus, identifying him as a fertility spirit, and seemingly as hump-backed, so with Kokopelli, but this does not mean the figure is Kokopelli since the figure could as easily simply be bending forward as he plays. A more likely candidate for the famous Kokopelli image is Paiyatuma since, as noted, Paiyatuma is also associated with fertility but also with the flute, as illustrated by the legend below.

Text

The following text is taken from Voices of the Winds: Native American Legends by Margot Edmonds and Ella Clark. The story is another version of the first part of Paiyatuma and the Maidens of the Corn.

How the Zunis wished for new music and new dances for their people when they participated in ceremonials!

Their Chief and his counsellors decided to ask their Old Grandfathers for help. They journeyed to the Elder Priests of the Bow and asked, "Grandfathers, we are tired of the same old music and the old dances. Can you please show us how to make new music and new dances for our people?"

After much conferring, the Elder Priests arranged to send our Wise Ones to visit the God of Dew. Next day, the four Wise Ones set out upon their mission.

Slowly climbing a steep trail, they were pleased to hear music coming from the high Sacred Mountain. Near the top, they discovered that the music came from the Cave of the Rainbow. At the cave's entrance vapors floated about, a sign that within was the god Paiyatuma.

When the four Wise Ones asked permission to go in, the music stopped; however, they were welcomed warmly by Paiyatuma, who said, "Our musicians will now rest while we learn why you have come."

"Our Elders, the Priests of the Bow, directed us to you. We wish for you to show us your secret in making new sounds of music. Also with the new music, we wish to learn how to create new ceremonial dances.

"As gifts, our Elders have prepared these prayer sticks and special plume-offerings for you and your people."

"Come sit with me," responded Paiyatuma. "You shall now see and hear."

Before them appeared many musicians with beautifully decorated long shirts. Their faces were painted with the signs of the gods. Each held a lengthy tapered flute. In the center of the group was a large drum beside which stood its drum-beater. Another musician held the conductor's wand. These were men of age and experience, graced with dignity.

Paiyatuma stood and spread some magic pollen at the feet of the visiting Wise Ones. With crossed arms, he then strode the length of the cave, turning and walking back again. Seven beautiful young girls, tall and slender, followed him. Their garments were similar to the musicians but were of various colors. They held hollow cottonwood shafts from which bubbled dainty clouds when the maidens blew into them.

"These are not the maidens of corn," Paiyatuma said. "They are our dancers, the young sisters from the House of Stars."

Paiyatuma placed a flute to his lips and joined the circle of dancers. From the drum came a thunderous beat, shaking the entire Cave of the Rainbow, signaling the performance to begin.

Beautiful music from the flutes seemed to sing and sigh like the gentle blowing of the winds. Bubbles of vapor arose from the girls' reeds. In rhythm, the Butterflies of Summerland flew about the cave, creating their own dance forms with the dancers and the musicians. Mysteriously, over all the scene flooded the colors of the Rainbow throughout the cave. All of this harmony seemed like a dream to the four Wise Ones, as they thanked the God of Dew and prepared to leave.

Paiyatuma came forward with a benevolent smile and symbolically breathed upon the four Wise Ones. He summoned four musicians, asking them to give each one a flute as a gift.

"Now depart to your Elders," said Paiyatuma. "Tell them what you have seen and heard. Give them our flutes. May your people, the Zuni, learn to sing like the birds through these woodwinds and these reeds."

In gratitude, the Wise Ones bowed deeply and accepted the gifts, expressing their appreciation and farewell to all of the performers and Paiyatuma.

Upon the return of the four Wise Ones to their own ceremonial court, they placed the four flutes before the Priests of the Bow. The Wise Ones described and demonstrated all that they had seen and heard in the Cave of the Rainbow.

Chief of the Zuni tribe and his counsellors were happy with their new knowledge, returning to their tribe with the gift of the flutes and the reeds. Before their next ceremonial, many of their tribesmen learned to make new music and to create new dances for all their people to enjoy.