John Wesley Cromwell (l. 1846-1927) was an African American civil rights activist, educator, historian, journalist, and lawyer who wrote extensively on slave revolts, especially Nat Turner's Rebellion of 1831. Drawing on primary sources, Cromwell wrote The Aftermath of Nat Turner's Insurrection, published in 1920. The article focuses on the immediate effects of the revolt and its legacy.

Between 21-23 August 1831, Nat Turner (l. 1800-1831), an educated slave and lay preacher in Southampton County, Virginia, led the deadliest slave rebellion in US history, killing c. 55-65 White people (Cromwell puts the number at 61) before the revolt was put down. Turner escaped capture on 23 August, when his band was defeated by state militia at the Belmont Plantation, and then eluded a manhunt until he was discovered by the farmer Benjamin Phipps on 30 October and delivered to jail in Jerusalem, the county seat, on the 31st. He was tried on 5 November, found guilty, and hanged on 11 November 1831.

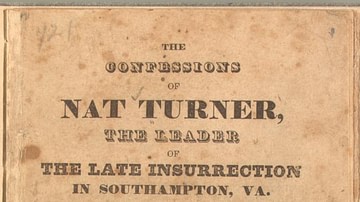

While in jail, Turner was interviewed by the attorney T. R. Gray (l. c. 1800-1834), who was not his legal counsel but only an interested party, and Gray's transcript was published in November 1831 as The Confessions of Nat Turner, which became a bestseller. In the Confessions, Turner discusses the inspiration for the revolt and the murders of the citizens of Southampton County once the rebellion was launched. Cromwell adds another dimension to the story by focusing on events in Southampton (and other regions) between 23 August, when the revolt was crushed, and 11 November when Turner was hanged.

The immediate aftermath of Nat Turner's Rebellion (also known as the Southampton Insurrection) was an attack on the Black community – in Southampton and elsewhere – as White citizens feared a large-scale uprising which, they thought, Turner was only one part of.

Cromwell, in describing and explaining the retaliation of the White community, notes the panic that gripped slave-holding states after Turner's revolt and how no one actually knew what was going on or what might come next until Turner's capture and subsequent confession. One of T. R. Gray's stated objectives in publishing the Confessions, in fact, was to assure the White community that Turner had acted alone and there was no need to fear a larger conspiracy of rebel leaders among the slave population. Almost 100 years later, Cromwell's piece describes exactly what that fear looked like and how it was expressed in violence directed at Black people, both slave and free.

Cromwell was a prominent figure in 19th- and 20th-century America, well-versed in history and an eloquent writer and speaker. Editors John B. Duff and Peter M. Mitchell, introducing his piece in their The Nat Turner Rebellion: The Historical Event and the Modern Controversy, write:

John Wesley Cromwell was born a slave in Portsmouth, Virginia [in 1846]. After his father had earned the family's freedom, young Cromwell attended a private school for Negroes in Philadelphia. After teaching in Pennsylvania, he opened a school in Virginia and played a prominent role in the reconstruction politics of the state. Among other activities, Cromwell organized the Union League Clubs, was a member of the jury empaneled to try Jefferson Davis, and served in the Virginia Constitutional Convention, 1867-1868. Subsequently, he practiced law, edited a weekly newspaper, and taught in the public schools of the District of Columbia.

(97)

Having experienced slavery firsthand, Cromwell is sympathetic to Turner's cause and the event itself while acknowledging that, initially at least, the Turner Rebellion did far more harm than good to the Black community of Southampton County and elsewhere. Still, as Cromwell notes, Turner's Revolt also drew greater attention to the "peculiar institution" of slavery, riled up the abolitionists, and contributed to the growing tensions between slave states and free states that would eventually erupt in the American Civil War (1861-1865) and, finally, result in the passage of the Thirteenth Amendment and the end of slavery in the United States.

Text

The following excerpt from John Wesley Cromwell's The Aftermath of Nat Turner's Insurrection (first published in Journal of Negro History 5, April, 1920) is taken from The Nat Turner Rebellion: The Historical Event and the Modern Controversy, edited by John B. Duff and Peter M. Mitchell, pp. 97-112. It has been edited for space; omissions are indicated by ellipses.

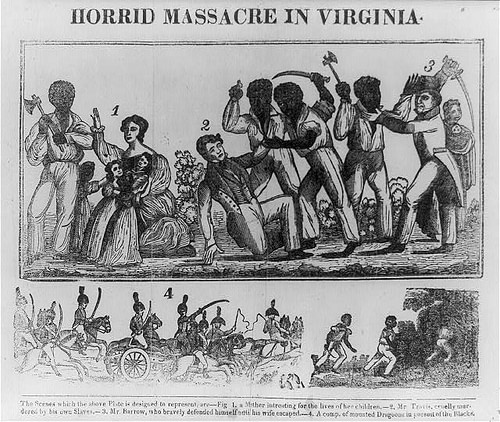

A reign of terror followed in Virginia. Labor was paralyzed, plantations abandoned, women and children were driven from home and crowded into nooks and corners. The sufferings of many of these refugees, who spent night after night in the woods, were intense. Retaliation began. In a little more than one day, 120 Negroes were killed. The newspapers of the time contained from day to day indignant protests against the cruelties perpetrated. One individual boasted that he himself had killed between ten and fifteen Negroes. Volunteer whites rode in all directions visiting plantations. Negroes were tortured to death, burned, maimed, and subjected to nameless atrocities. Slaves who were distrusted were pointed out and, if they endeavored to escape, they were ruthlessly shot down.

A few individual instances will show the nature and extent of this vengeance. "A party of horsemen started from Richmond with the intention of killing every colored person they saw in Southampton County. They stopped opposite the cabin of a free colored man who was hoeing in his little field. They called out, 'Is this Southampton County?' He replied, 'Yes, Sir, you have just crossed the line, by yonder tree.' They shot him dead and rode on."

A slaveholder went to the woods accompanied by a faithful slave, who had been the means of saving his master's life during the insurrection. When they reached a retired place in the forest, the man handed his gun to his master, informing him that he could not live a slave any longer, and requested either to free him or shoot him on the spot. The master took the gun, in some trepidation, leveled it at the faithful Negro, and shot him through the heart.

But these outrages were not limited to the Negro population…An Englishman, named Robinson, was engaged in selling books at Petersburg. An alarm being given one night that five hundred blacks were marching against the town, he stood guard with others at the bridge. After the panic had a little subsided, he happened to make the remark that the blacks, as men, were entitled to their freedom and ought to be emancipated. This led to great excitement and the man was warned to leave town. He took passage in the stagecoach, but the vehicle was intercepted. He then fled to a friend's home, but the house was broken open and he was dragged forth. The civil authorities informed of the affair refused to intervene. The mob stripped him, gave him a considerable number of lashes, and sent him on foot naked under a hot sun to Richmond, whence he, with difficulty, found passage to New York.

Believing that Nat Turner's insurrection was a general conspiracy, the people throughout the State were highly excited. [Militia and other armed forces were mobilized across the state]. The revolt was subdued, however, before these troops could be placed in action and about all they accomplished thereafter was the terrifying of Negroes who had taken no part in the insurrection and the immolation of others who were suspected.

Sixty-one white persons were killed. Not a Negro was slain in any of the encounters led by Turner. Fifty-three Negroes were apprehended and arraigned. Seventeen of the insurrectionists were convicted, and executed, twelve convicted and transported, ten acquitted, seven discharged, and four sent on to the Superior Court. Four of those convicted and transported were boys. There were brought to trial only four free Negroes, one of whom was discharged and three held for subsequent trial were finally executed. It is said that they were given a decent burial.

The news of the Southampton Insurrection thrilled the whole country, North as well as South. The newspapers teemed with the accounts of it. Rumors of similar outbreaks prevailed all over the State of Virginia and throughout the South. There were rumors to the effect that Nat Turner was everywhere at the same time. People returned to their home before twilight, barricaded themselves in their homes, kept watch during the night, or abandoned their homes for centers where armed force was adequate to their protection. There were many such false reports as the one that two maid servants in Dinwiddie County had murdered an old lady and two children. Negroes throughout the State were suspected, arrested, and prosecuted on the least pretext and in some cases murdered without any cause. Almost any Negro having some of the much-advertised characteristics of Nat Turner was in danger of being run down and torn to pieces for Nat Turner himself…

The excitement in other States was not much less than in Virginia and North Carolina. In South Carolina, Governor Hayne issued a proclamation to quiet rumors of similar uprisings. In Macon, Georgia, the entire population rose at midnight, roused from their beds by rumors of an impending onslaught. Slaves were arrested and tied to trees in different parts of the state, while captains of the militia delighted in hacking at them with swords. In Alabama, rumors of a joint conspiracy of Indians and Negroes found ready credence. At New Orleans, the excitement was at such a height that a report that 1,200 stands of arms were found in a black man's house was readily believed.

But the people were not satisfied with this flow of blood and passions were not subdued with these public wreakings. Nat Turner was still at large. He had eluded their constant vigilance ever since the day of the raid in August. That he was finally captured was more the result of accident than of design.

A dog belonging to some of Nat Turner's acquaintances scented some meat in the cave and stole it one night while Turner was out. Shortly after, two Negroes, one the owner of the dog, were hunting with the same animal. The dog barked at Turner, who had just gone out to walk. Thinking himself discovered, Turner begged these men to conceal his whereabouts, but they, on finding out who it was, precipitately fled.

Concluding from this that they would betray him, Turner left his hiding place, but he was pursued almost incessantly. At one time, he was shot at by one Francis near a fodder stack in a field, but happening to fall at the moment of discharge, the contents of the pistol passed through the crown of his hat. The lines, however, were closing upon Turner. His escape from Francis added new enthusiasm to the pursuit and Turner's resources, as fertile as ever, contrived a new hiding place in a sort of den in the lap of a fallen tree over which he placed fine brush.

He protruded his head as if to reconnoiter about noon, Sunday, October 30, when a Benjamin Phipps, who had that morning for the first time turned out in pursuit, came suddenly upon him. Phipps, not knowing him, demanded, "Who are you?" He was answered, "I am Nat Turner." Phipps then ordered him to extend his arms and Turner obeyed, delivering up a sword which was the only weapon he then had.

This was ten weeks after that Sunday in August [when the revolt began]. At the time of the capture, there were at least fifty men in search of him, none of whom could have been two miles from the hiding place…His arrest caused much relief. He was taken the next day to Jerusalem, the county seat, and tried on the fifth of November before a board of magistrates. The indictment against him was for making insurrection and plotting to take away the lives of diverse free white persons on the twenty-second of August 1831. On his arraignment, Turner pleaded "Not Guilty." The Commonwealth submitted its case, not on the testimony of any eyewitnesses but on the depositions of one Levi Waller who read Turner's Confession and Colonel Trezevant, the committing magistrate, corroborated it by referring to the same confession. Turner introduced no testimony in defense and his counsel made no argument in his behalf. He was promptly found guilty and sentenced to be hanged Friday, November 11, 1831, twelve days after his capture. During the examination, Nat evinced great intelligence and much shrewdness of intellect, answering every question clearly and distinctly and without confusion or prevarication.

An immense throng gathered on the day of execution, though few were permitted to see the ceremony. He exhibited the utmost composure and calm resignation. Although assured, if he felt it proper, he might address the immense crowd, he declined to avail himself of the privilege, but told the sheriff in a firm voice that he was ready. Not a limb or muscle was observed to move. His body was given over to the surgeons for dissection. He was skinned to supply such souvenirs as purses, his flesh made into grease, and his bones divided as trophies to be handed down as heirlooms. It is said that there still lives a Virginian who has a piece of his skin which was tanned, that another Virginian possesses one of his ears, and that the skull graces the collection of a physician in the city of Norfolk…

So many ills of the Negro followed…that one is inclined to question the wisdom of the insurgent leader…Considered in the light of its immediate effect upon its participants, it was a failure, an egregious failure, a wanton crime. Considered in its necessary relation to slavery and as contributory to making it a national issue by the deepening and stirring of the then-weak local forces, that finally led to the Emancipation Proclamation and Thirteenth Amendment, the insurrection was a moral success and Nat Turner Deserves to be ranked with the greatest reformers of his day.

This insurrection may be considered an effort of the Negro to help himself rather than depend on other human agencies for the protection which could come through his own strong arm; for the spirit of Nat Turner never was completely quelled. He struck ruthlessly, mercilessly, it may be said, in cold blood, innocent women and children; but the system of which he was the victim had less mercy in subjecting his race to the horrors of the "middle passage" and the endless crimes against justice, humanity, and virtue, then perpetrated throughout America. The brutality of his onslaught was a reflex of slavery, the object lesson which he gave brought the question home to every fireside until public conscience, once callous, became quickened, and slavery was doomed.