The Battle of Białystok-Minsk in Jun-Jul 1941, which involved the encirclement of entire Soviet armies positioned near each city in Poland and Belarus, respectively, was one of the first victories by Nazi Germany and its Axis allies against the USSR's Red Army during Operation Barbarossa in the Second World War (1939-45). Over 330,000 Soviet prisoners of war were taken, and the route to Moscow opened.

Operation Barbarossa

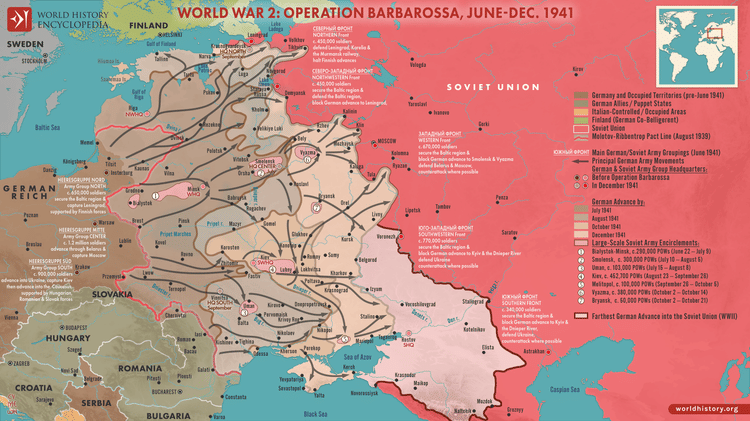

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, was confident after swift victories in the Low Countries and France in 1940, that he could make even greater territorial and resource gains in 1941 by attacking the USSR. The Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the USSR back in August 1939, was shown to be a mere agreement of convenience until Hitler was ready to wage war in the east. The Pact had awarded the USSR control of the eastern half of Poland, Bessarabia, Finland (which successfully resisted), Estonia, Latvia, and Lithuania. Germany took western Poland, gained certain resources delivered by the USSR, and ensured Hitler did not have to fight on two fronts while he attacked Western Europe. Hitler, now determined to find Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper, launched Operation Barbarossa on 22 June 1941. The overall objective was to smash the USSR's Red Army and take control of several key cities, which would give Germany and its Axis allies access to natural resources from Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) to Ukraine. The invading force, made up of German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men in 153 divisions, 3,600 tanks, and 2,700 aircraft (Dear, 86). The overall commander was Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). With the largest army in history, Hitler assured his generals that victory would come before the winter.

Operation Barbarossa involved three Axis army groups: North, Centre, and South, commanded respectively by Field Marshals Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb (1876-1956), Fedor von Bock (1880-1945), and Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953). There were also three air force groups. The front stretched from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The overall objective of the first phase of Operation Barbarossa was to eliminate the Red Army west of the rivers Dvina and Dnieper (Dnepr/Dnipro).

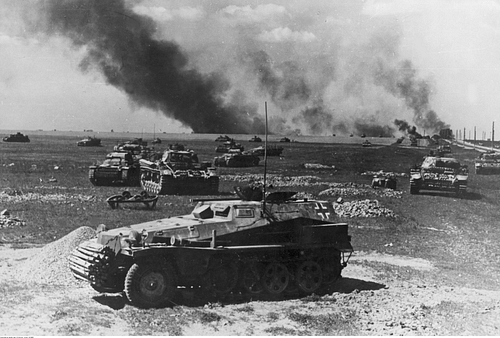

As Hitler had predicted, the Axis forces won several quick victories. Air supremacy was achieved within a few days after some 2,500 Soviet aircraft were destroyed, mostly on the ground. Axis troops moved through the defences according to their Blitzkrieg ('lightning war') plan of combining air support with fast-moving armoured and motorised infantry divisions. The Red Army was surprised not by the attack but the scale and speed of it. As Army Group Centre raced forward at a pace of 37 miles (60 km) a day, the first major victory came at the double battle of Białystok-Minsk. The battle involved the encirclement and defeat of two cities: Białystok, close to the northeastern border of Soviet-occupied Poland, and Minsk in Belarus.

Opposing Armies

Bock was an experienced commander, the archetypal Prussian officer and career militarist. He had displayed excellent command abilities during the invasion of Poland in 1939 and in the victories in France, for which he was promoted to field marshal. Bock was particularly adept at marshalling large numbers of troops and moving them at high speed against the enemy. For the campaign against the USSR, Bock's Army Group Centre included divisions of the 4th Army, the 9th Army, and several other units, including several panzer groups, amongst which were five divisions of 2nd Panzer Group led by the Blitzkrieg master Heinz Guderian (1888-1954), "one of the world's foremost theorists and practitioners of armoured warfare" (Kirchubel, 17). The other main panzer commander was Hermann Hoth (1885-1971), "a team player and a good man in a crisis" (ibid, 16). It was Bock's plan to use a massive pincer movement (Zangenangriff) to overpower the enemy with his fast-moving panzer divisions, punching through the thin Red Army lines and ultimately entirely enveloping the enemy en masse. Then the slower infantry would follow and mop up the shattered enemy formations whose command and communication systems would by then be in complete disarray.

The Red Army in this sector consisted of four separate armies commanded overall by General Dmitry Grigorevich Pavlov (1897-1941). Pavlov, under orders to adopt defensive positions, set a wide front of three of his armies, with one held back as a reserve. The USSR's leader, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), had forbidden any retreat away from the Western Front. Stalin was more worried about Hitler grabbing resource-rich Ukraine in the south, and so he had stationed his best troops and best commanders there. Stalin forbade Pavlov to make any preemptive attacks or advance in any way. As a consequence, despite the knowledge of a build-up of Axis forces, Pavlov was not permitted to conduct air reconnaissance or use preemptive artillery fire. Pavlov was also at a disadvantage in terms of equipment, since most Red Army weapons, and especially his tanks, were inferior to those of the Axis attackers. On top of all that, the Soviet defences remained unfinished; a German post-operation report noted that "only 193 of the 1,175 forts throughout the [USSR's] West Front area were equipped and occupied" (Kirchubel, 29). Finally, Pavlov himself contributed to his own downfall by spreading his troops too thinly and depriving himself of an adequate mobile reserve. Perhaps more seriously, given how the battle played out, Pavlov adhered to the mistaken belief that tanks were best used in small groups as support for infantry. All of these weaknesses would be exploited to the full by the Axis forces and especially by the panzer commanders.

Pavlov was perhaps caught by surprise because the Axis pincer movement was initiated from a relatively straight front at the beginning of the battle. Two panzer groups sped forward, one commanded by Guderian and the other by Hoth. The Axis Blitzkrieg tactics combined devastating air attacks, artillery bombardments, and tank penetrations, overwhelming the enemy, often through a very narrow front. As Marshal Georgi Zhukov (1896-1974), the Soviet Union's best commander but who was then stationed in the south, noted after the war, the Red Army high command had not "calculated that the enemy would concentrate such a mass of armored and motorized forces and hurl them in compact groups on all strategic axes on the first day" (Kirchubel, 27). The Red Army had hoped to have time to absorb an initial attack and then regroup and counterattack, but this proved impossible when the enemy was determined to focus on speed and penetration.

Białystok

Many bridges were captured intact – despite having been prepared with explosives – and where necessary, rafts were built to carry vehicles to the opposite bank. Initially, the two Axis panzer groups advanced in parallel, but then they slowly moved in towards each other. The meeting point was east of Białystok. Hoth made the best progress of all, his panzer divisions charging right through the Soviet lines by the second day of the operation. Guderian made similar gains with his panzers. The Red Army did have a number of superior T34 tanks, but not enough, and their crews were inexperienced with this formidable new weapon. The majority of Red Army tanks were no match at all for the German panzers and artillery. Hundreds of Soviet tanks, poorly armoured and even more poorly deployed, were blasted out of service in the first 36 hours. Indeed, in a straight face-off between troops of similar weaponry, the Axis forces greatly benefitted from their real-war experience in Poland and France and usually came off best. The invading motorised troops did have their problems, notably the amount of dust from the dirt roads, which often clogged up engines and delayed the advance.

The question soon arose for the German commanders as to how to best exploit these quick territorial gains. In the end, Bock was directed to try and capture Minsk. To that end, Hoth was sent on towards Vitebsk and Polotsk while Guderian headed for Slutsk, Bobruisk (Babruysk), and Rogatchev (Rahachow). Meanwhile, the Axis motorised infantry and other infantry divisions came up from behind them and attacked the remaining Red Army troops caught near Białystok. Pavlov could have avoided the entrapment if he had been allowed to retreat. Lack of military intelligence and the speed of the invasion certainly limited Pavlov's ability to send troops where they were most needed. The Axis forces at Grodno (Hrodna) and those attacking the fortress of Brest-Litovsk faced heavy resistance, but elsewhere, it was often a case of the Red Army arriving at a place where the German panzers had been instead of where they actually were. The Red Army also fought better when the invaders, notably Hoth's group, began to hit forested areas.

Minsk

Both Guderian and Hoth pressed on another 200 miles (325 kilometres) and repeated their parallel thrust trick, this time on the city of Minsk. It was here that the first closed pocket was achieved – what the German Army called a cauldron or Kessel. Even here, though, some Red Army units managed to sneak through gaps, such was the scale of the territory involved. On 28 June, Hoth's panzers were the first to enter Minsk. Guderian arrived the next day, but, determined to speed on across the Dnieper and on to Moscow, he failed to close off the pocket completely, which allowed more Red Army units to retreat. This was a symptom of the operational differences between Hitler and his commanders on the ground. Hitler wanted to destroy the Red Army in the field, while personally-ambitious commanders were more keen to take symbolic and glamorous targets like big cities. For Minsk, though, the fact the pocket was not entirely sealed until 29 June became irrelevant, such were the forces ranged against it in the long hot days of that summer of 1941. The Belarusian capital had already been softened up by virtually unopposed Axis bombing raids, attacks that also targeted Soviet supply dumps and rail networks to the east, preventing reinforcements from arriving.

The Axis armies were becoming a little too stretched out for comfort. The slower infantry and artillery units, moving on poor roads and heavily dependent on horses, simply could not keep pace with the panzer divisions charging ahead. Eventually, though, the huge pockets of isolated Red Army troops – there had been four in all – were closed down through the first week of July. The areas involved were huge and often forested, meaning sporadic fighting went on for weeks far behind the main front lines. Many Red Army soldiers fought on, often without any command structure, because they were convinced if they surrendered they would be shot or poorly treated; an assessment that turned out to be accurate. One German infantry soldier, Ernst-Günter Merten, noted: "These bloody Russian forests! One loses the overview of who is a friend and who is an enemy. So we are shooting at ourselves" (Stahel, 182).

Minsk would be the last stand of the Red Army in Belarus. One Soviet soldier, Georgy Semenyak, gives an account of the chaos of an army in retreat towards Minsk:

I fought on the border for three days and three nights. The bombing, shooting…explosions of artillery gunfire continued non-stop...It was a dismal picture. During the day, aeroplanes continuously dropped bombs on the retreating soldiers…The lieutenants, captains, second-lieutenants took rides on passing vehicles…mostly trucks travelling eastwards…[there were] virtually no commanders. And without commanders, our ability to defend ourselves was so severely weakened that there was really nothing we could do…

(Rees, 44)

On the other side, a German soldier, Albert Schneider, was enjoying the war immensely:

You thought it was a doddle…[we thought] we will have a splendid life and the war will be over in six months – a year at the most – we will have reached the Ural Mountains and that will be that…At the time we also thought, goodness, what can happen to us? Nothing can happen to us. We were, after all, the victorious troops. And it went well and there were soldiers who advanced singing! It is hard to believe but it's a fact.

(Rees, 43-4)

Despite the chaos, many Red Army units resisted the attack on Minsk, firing from their prepared defences until they ran out of ammunition and had to surrender. Bock noted that "In spite of the heaviest fire and the employment of every means the crews refuse to give up. Each fellow has to be killed one at a time" (Dimbleby, 179). The great city of Minsk eventually fell into Axis hands on 3 July. Resistance in the pocket to the west ended on 9 July.

Army Group Centre had destroyed 22 Red Army infantry divisions, 7 armoured divisions, 3 cavalry divisions, and 6 motorised brigades (Liddell Hart, 120). Around 342,000 Soviet prisoners were taken, 3,332 tanks captured, and 1,809 heavy guns captured or destroyed (Kirchubel, 39). The figures were enormous, but this would be the enduring trend of the German-Soviet War. The Nazi regime soon installed itself in the city, and thousands of executions of civilians suspected of being partisans or collaborators were carried out. Jewish people were a particular target, and those who were not immediately shot were rounded up – 80,000 people – and confined inside ghettos surrounded by watchtowers. Atrocities were committed here with a terrible frequency.

Aftermath

The USSR's Western Front had completely collapsed in less than two weeks. The invasion so far had resulted in one million casualties. The Axis forces had made a deep penetration into enemy territory, but there had been losses in material and men, losses which, although not crucial in the first months, would, through their steady accumulation, prove to be significant as the campaign lasted much longer than had been anticipated. The invaders now realised that the Red Army would fight to the bitter end, that the roads were awful, the spaces almost endless, and that there were few, if any, opportunities to live off the land. This front of the war was to become the deadliest of WWII.

After the battle, Stalin had General Pavlov and some of his immediate subordinates arrested and executed. In response to the loss and the Axis atrocities perpetrated by the Einsatzgruppen killing squads, such as the mass murder of captured Communist officials and Jewish people, Stalin rebranded the conflict a great 'Patriotic War'. As the war now entered Russian territory, Stalin stated that everyone must offer nothing less to the enemy than a 'relentless struggle'. Punishments were imposed on those who did not fight as required, and partisans were encouraged to sabotage the enemy behind the front lines. Hitler, meanwhile, was already planning his victory parade in Moscow.

The Axis armies marched on and, repeating the gigantic encirclement strategy, won the Battle of Uman (July-Aug), the Battle of Smolensk in 1941 (July-September), and the Battle of Bryansk (aka Battle of Briansk-Vyazma, October). Many more battles followed across the front as Hitler ordered the bulk of his forces to the north around Leningrad and to the south to Ukraine, with the objective of capturing material and industries useful for the war effort. In the Battle of Moscow (October 1941 to January 1942), the Red Army, led by the gifted Zhukov, held its position and then launched a fightback. As autumn turned to winter, the invading army's inadequate reserves, lack of winter equipment, and the problems of logistical supply over vast regions with poor roads began to tell. Operation Barbarossa had failed in its strategic objectives. Hitler regrouped his resources and again tried for a major push from the spring of 1942, but now the Eastern Front (aka the German-Soviet War) would drag on for three more years of bitter fighting, ultimately ending with Soviet victory in May 1945 as Germany itself was overran.