The Battle of Smolensk in 1941 ended in victory for Nazi Germany and its Axis allies against the USSR's Red Army during Operation Barbarossa in the Second World War (1939-45). Smolensk on the Dnieper (Dnepr/Dnipro) river was the traditional gateway to Moscow but was captured by the end of July using a combination of tank and infantry divisions.

The Axis forces had used a large pincer movement to encircle the Red Army west of Smolensk. After the battle, around 340,000 prisoners were taken, and the Russian capital was now in the invaders' sights. Progress through the USSR had come at a high cost in men and material, though, while the Red Army remained ready and willing to fight on. The Battle of Smolensk and its high rate of attrition revealed that the Blitzkrieg ('lightning war') tactics of using fast-moving armoured divisions with air and infantry support while attacking on a narrow front could not work in the longer term in the vast spaces of the Soviet Union.

Operation Barbarossa

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, was confident after swift victories in the Low Countries and France in 1940, that he could make even greater territorial and resource gains in 1941 by attacking the USSR. The Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the USSR back in August 1939, was shown to be a mere agreement of convenience until Hitler was ready to wage war in the east. Hitler, as he had always promised, was determined to find Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper.

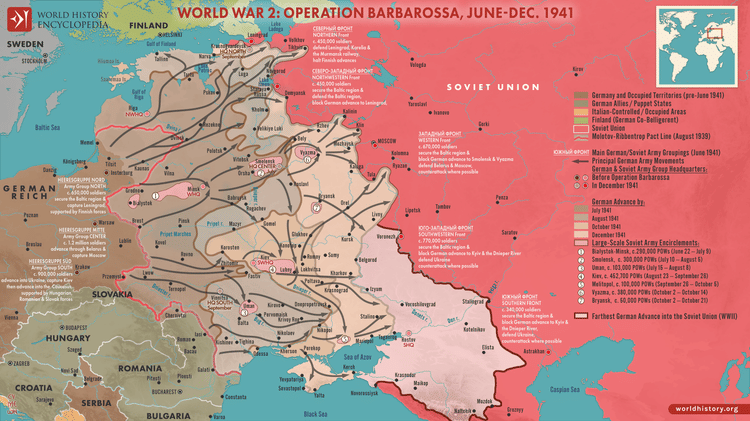

Operation Barbarossa, the code name for the attack on the USSR, was launched on 22 June 1941. The overall objective was to smash the USSR's Red Army west of the Western Dvina and Dnieper rivers and take control of several key cities, which would give Germany and its Axis allies access to natural resources from Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) to Ukraine. The invading force, made up of German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men in 153 divisions, 3,600 tanks, and 2,700 aircraft (Dear, 86). The overall commander was Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). With the largest army in history, Hitler assured his generals that victory would come before the winter.

The Axis force was divided into three army groups: North, Centre, and South. At the Battle of Białystok-Minsk in June-July 1941, four Soviet armies commanded by General Dmitry Grigorevich Pavlov (1897-1941) were overwhelmed by Army Group Centre commanded by Field Marshal Fedor von Bock (1880-1945). The invaders sped through Soviet-occupied eastern Poland and Belarus using the Blitzkrieg tactics that had served them so well in Poland and Western Europe. Blitzkrieg involved a combination of massive air support with artillery bombardments and fast-moving armoured and motorised infantry divisions. With Minsk captured by a giant pincer movement (Zangenangriff), Bock's two main panzer commanders, Heinz Guderian (1888-1954) and Hermann Hoth (1885-1971), sped on eastwards. The next target was the city of Smolensk on the Dnieper.

The Red Army

The Red Army was hampered by several factors in the initial stages of Operation Barbarossa. First, the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), had forbidden any retreat away from their Western Front and prohibited any offensive actions. In addition, Pavlov had spread his defences too thin, and these were easily punctured by the Axis armoured divisions. Pavlov also failed to exploit his armour and, instead, wasted most of his tanks by using them only in small groups. The tanks were also mostly inferior to the enemy's. The Red Army did have a number of superior T34 tanks, but not enough, and their crews were inexperienced with this formidable new weapon. On top of all that, the Soviet static defences remained unfinished in June 1941, and the troops had very little battle experience, unlike the Axis forces.

Although overwhelmed at Białystok and Minsk, where over 340,000 Soviet prisoners were taken, the Red Army soldiers did fight tenaciously, even when their command structure was seriously compromised. The Red Army was also fighting in irregular units in areas protected by forests and marshes, which proved impossible to clear completely. Stalin had called for partisans to sabotage the invaders' supply lines and the large gaps created between the fast-moving motorised units and much slower artillery and infantry troops. The Axis units were also experiencing problems due to the lack of proper roads and the dust in that long, hot summer, which clogged up the engines of tanks and trucks. It proved very difficult to live off the land, too. Still, the Axis army ploughed on across nearly 300 miles (475 km) of enemy territory to try and take Smolensk. There, the Red Army waited for the invaders. Marshal Semyon Timoshenko (1895-1970), who had been in overall command of the Red Army from the start, took over the management of the Soviet Western Front on 2 July.

The Smolensk Kessel

Timoshenko had at his disposal five separate armies. Two massive defensive lines some 200 miles (320 km) long blocked the Axis route to Moscow. Hitler, aware of these lines thanks to air reconnaissance, wrote to his ally Benito Mussolini (1883-1945), leader of Fascist Italy: "The might and resources of the Red Army are far in excess of what we knew or even considered possible" (Kirchubel, 47). That message was sent on 30 June, but even by 8 July, the Axis generals in the field were still underestimating the enemy. The German commanders of the two panzer spearheads at Smolensk believed they faced 11 divisions when actually, thanks to massive reinforcements being sent, the Red Army under Timoshenko had 66 divisions, plus sizeable reserves. The Axis advance was slowed by heavy rain, the poor roads, and the necessity to rebuild destroyed bridges as it moved eastwards, but, nevertheless, it rumbled on, taking town after town as it relentlessly moved forward.

Hoth and Guderian managed to break through Tomoshenko's defensive lines west of Smolensk and led their panzer groups in a giant pincer movement to the outskirts of the city through the first week of July. Smolensk was a transport hub and commercial and religious centre of historical importance. Not for the first time, an invading army heading for Moscow had to take control of this city before it could move on. Hoth had swept forward from Vitebsk and covered the northern side of Smolensk. Guderian had crossed the Dnieper at Kopys and, despite facing heavy Soviet resistance, approached Smolensk from the southwest. By 16 July, as at Minsk, a huge pocket, what the German Army called a cauldron or Kessel, was created, which attempted to cut off the Red Army from the units retreating from the Soviet Western Front and the reinforcements coming from the east. Once again, though, the relatively small size of the German advance armoured units, still separated from their infantry, meant that a thin encirclement did not mean instant victory, and there were still plenty of sizeable holes in what was, in reality, a rather leaky cauldron.

The infantry divisions, heavily dependent on horses to pull their artillery, supplies, and equipment, could only manage on average 20 miles (32 km) a day compared to the 60 miles (96 km) achieved by the motorised divisions. The Red Army, caught in the middle, was far from giving up either. General Gotthard Heinrici (1886-1971), a German infantry commander, remarked, "The Russians are very strong and fight with desperation. They appear suddenly all over the place, shooting, falling upon columns, individual vehicles, messengers etc…our losses are considerable" (Trigg, 189). Red Army snipers were a particular problem. Not until 26-27 July did the Axis high command consider the Smolensk Kessel closed, but even then, there was still a ten-mile (16-km) gap near Yartsevo. Within the pocket were three Soviet armies, around 400,000 men.

Timoshenko launched significant counterattacks from mid-July. The flanks of Hoth and Guderian were attacked from inside the pocket and from the outside, delaying the total closure of the Kessel. Fighting at Yelnya was particularly fierce and further depleted the Axis advance forces, particularly in terms of ammunition shortages and tank losses. Many panzer divisions were down to less than 50% of their full strength. This was going to be a much sterner test than the previous month's battles. As Bock noted on 26 July:

It turns out that the Russians have completed a new, concentrated build-up around my projecting front. In many places they have tried to go over to the attack. Astonishing for an opponent who is so badly beaten; they must have unbelievable masses of material, for even now the field units still complain about the powerful effect of the enemy artillery. The Russians are also becoming more aggressive in the air.

(Stahel, 299)

The Soviet artillery, as Bock noted, was proving remarkably effective, and this would become a feature of the Eastern Front. The Red Army was able to field a new and devastating weapon, the BM-13 Katyusha multiple rocket launcher. This weapon could fire 132 mm rockets in barrages lasting ten seconds. One veteran German soldier remembered that this weapon, nicknamed 'Stalin's organs', was "the most terrible and shocking thing I have ever encountered" (Stahel, 299).

In Smolensk itself, the city's bridges across the Dnieper (which divided the city in two) were blown up, and the defenders were ordered to fight to the last man. The Axis panzer divisions were back in action after taking a brief rest for a few days to regroup, refit, and redistribute material by breaking up the most destitute divisions to bulk up the remainder. In the end, the struggle to control Smolensk became a series of fierce street battles as the Axis infantry finally caught up with the action on the front line. The attackers benefitted from massive air support, the Axis air force flying 1,500 sorties between 14 and 16 July. In the second half of July, over 12,500 sorties were flown (compared to 5,200 by the Soviet air force). The Junkers Ju 87 'Stuka' dive bombers caused havoc amongst the Soviet tank columns within the Smolensk pocket. Meanwhile, heavier bombers repeatedly attacked Smolensk itself. A German bomber crew member, Hans Vowinckel, recorded: "Smolensk is burning – it was a monstrous spectacle…We didn't need to look for our objective, the blazing torch lit our way through the night from far away" (Trigg, 190).

With the infantry divisions now in action within the pocket, some of the Axis armour could move eastwards, capturing Red Army reinforcements heading for Smolensk, such as trainloads of new T34 tanks. On 16 July, the Axis forces took control of Smolensk's main train line and main road.

Smolensk fell into Axis hands on 22 July. The pocket to the west of the city was not finally cleared and eliminated until 5 August. Again, a huge number of Red Army prisoners were taken, some 300,000, along with 3,205 tanks, 3,120 guns, and 1098 aircraft (Kirchubel, 58). A second isolated pocket yielded another 38,000 prisoners. Hitler flew to the Army Group Centre headquarters to personally congratulate Bock and his staff.

Aftermath

As at captured cities like Minsk, the Nazi regime soon installed itself in Smolensk, and thousands of executions of civilians suspected of being partisans or collaborators were carried out. Jewish people were another particular target. Einsatzgruppen, mobile Nazi killing squads, committed atrocities everywhere.

Hitler halted any attack on Moscow and instead sent the bulk of his forces to the North and South to take Leningrad and resource-rich Ukraine, respectively. Hitler later changed his mind and commanded his forces to attack Moscow after all. So far in the campaign, there had been great victories, but there had also been great losses in material and men – 200,000 men and 1300 tanks by Army Group Centre alone. Such losses, although not crucial in the first months, would, through their steady accumulation, prove to be significant as the campaign lasted much longer than had been anticipated. In addition, the resupply of men and materials was woefully inadequate. A high number of experienced men and officers had been lost, there were practically no strategic reserves left, and everything from artillery shells to bolts for tank tracks were in extremely short supply.

In short, the Red Army had blunted the Axis Blitzkrieg, and, so long as the front was maintained, irrespective of where it actually was, the USSR remained strategically undefeated and able to continue a war of attrition that the invaders could not win, given the scale of the territory involved. Hitler's gamble on a quick knock-out punch had failed. With hindsight, then, the Battle of Smolensk indicated that a new form of fighting other than Blitzkrieg was required and, even more importantly, Germany and its allies could not win the war with the resources they had available.

The Soviet fightback began at the Battle of Moscow (October 1941 to January 1942). The German-Soviet War entered a new phase, one which would last for four more years and result in more deaths than in any other theatre of WWII. In the Battle of Smolensk in 1943, the Red Army regained control of the city as it advanced westwards. In May 1945, Berlin was occupied by the USSR, and Germany surrendered.