The Christianization of Iceland was a smooth transition compared to other Scandinavian countries. While in Norway, Denmark, or Sweden, royal authority played a crucial role in conversion, in Iceland, it was a parliamentary decision, reached by mediation and compromise. Although the Althing proclaimed that everyone should be baptized, private pagan worship and practices were tolerated, reflecting a pragmatic approach to balancing political necessity and community cohesion.

Political Evolution in Viking Age Iceland

The legendary settlement of Iceland, known as landnám (quite literally the land-taking), took place between approximately 870 and 930 as part of the larger Viking expansion across the North Atlantic. The island was likely discovered around 850, possibly by Scandinavian sailors who had been blown off course. The sources mention a couple of names associated with the island's sighting. First, a sailor from Norway, Naddod, was blown off course while sailing to the Faroe Islands around the mid-9th century, then Gardar Svavarsson from Sweden explored Iceland more systematically. He sailed around the island and confirmed it was a large landmass, settling briefly in Húsavík in the North (nowadays a whale-watching hotspot). Raven-Floki (Flóki Vilgerðarson) attempted a planned settlement in Iceland. He brought livestock but struggled with harsh winters, leading to the death of his cattle. Disheartened, he left, calling the island Ísland (Iceland), the name that eventually endured.

Tradition recognizes Ingólfr Arnarson as Iceland's first permanent settler, a Norwegian chieftain who left Norway allegedly due to conflicts related to King Harald Fairhair's unification efforts. Briefly put, around 874, he sailed to Iceland with his family and household, performed a ritual by throwing his high-seat pillars overboard, and settled where they landed, founding Reykjavík, but only after dealing with murderous slaves as tradition has it.

Shortly afterwards, news spread throughout Norse communities of vast, uninhabited land with rich pastures and ample fishing grounds. This sparked a wave of migration, primarily from Norway but also from Norse settlements in the British Isles, including Ireland, Scotland, and the Hebrides. Most early settlers were free farmers seeking new opportunities, though some were also minor chieftains. Many Norse settlers who arrived from the British Isles brought Gaelic wives, followers, and slaves, resulting in a mixed Norse-Gaelic population that left a lasting imprint on Icelandic culture.

The traditional date for Iceland's settlement, around 870, is supported by geological evidence, namely the tephra layer, a volcanic ash deposit from a known eruption at that precise time. Over the following decades, thousands of settlers arrived, and by around 930, most of the arable land had been claimed. This period is generally considered the end of the settlement phase and the beginning of the Icelandic Free State, a period that inspired many of the magnificent Icelandic sagas.

There were several reasons why so many people left their homelands to settle in Iceland. Many of those who came from Norway were fleeing the increasing power of King Harald Fairhair, whose efforts to unify Norway under his rule brought higher taxation and greater control over independent landowners. Others were drawn by the promise of free land and the opportunity to establish themselves without interference from kings or large landowners. Additionally, the wealth acquired through Viking raids in Britain and elsewhere in Europe provided the means for some families to finance the long journey and bring livestock and supplies with them. The settlers quickly adapted to their new environment, relying on livestock farming, hunting, and coastal fishing for survival. The island was heavily forested when they arrived, but large-scale tree-cutting for fuel, construction, and pasture led to rapid deforestation. Overgrazing by sheep and other livestock further contributed to soil erosion, a problem that would persist for centuries.

At first, land was taken freely, but as more people arrived, disputes arose over resources. These conflicts were usually resolved through negotiation and agreements among chieftains, rather than through large-scale warfare. The sagas, perhaps not surprisingly, rather tend to remember the troubles and conflicts. To maintain order in this new society, a decentralized system of governance was developed, unique in comparison to Europe's feudalism.

Local chieftains, known as goðar, played a crucial role in mediating disputes and leading communities. This title points out the bundling of political and religious power into a single function, with the chieftain being responsible for organizing rituals. Rather than forming a monarchy or centralized authority, wealth and power in medieval Iceland was distributed among chieftains and free farmers. Medieval Icelandic government had proto-democratic political structure, which culminated in the founding of the Althing in 930 at the site of Thingvellir near Reykjavik. The Althing served as a general assembly where laws were made, disputes were settled, and alliances were formed, marking the transition from a loosely organized settlement to an established commonwealth. Otherwise, the island was divided into 4 quarters and after a series of reforms, the number of chieftains would reach 48.

Crossroads between Paganism & Christianity

The settlement of Iceland was one of the last major land migrations in the Viking Age, creating a distinctive Norse society that remained independent for centuries. Isolated in the North Atlantic, the Vikings in Iceland developed a unique culture shaped by both Norse traditions and the realities of its harsh environment, elements that become visible in the Viking prophecy: the poem Völuspá of the Poetic Edda, the first mythological poem of the 13th-century collection. The poem, where god Odin requests the assistance of a völva (prophetess) in unlocking the secrets of the universe and its doom (Ragnarök), describes the attack of the giant Surt and his fiery sword. When relating the birth of the known world, Icelandic author and chieftain Snorri Sturluson describes in the Prose Edda the encounter of the ice realm Niflheim and the fiery lands of Muspell resulting in the birth of Ymir, the primordial giant. When speaking of the rivers flowing from Niflheim, he mentions a poisonous substance hardening and the poisonous vapours rising from ice and solidifying into rime – perhaps a poetic description of a volcanic eruption that lacked adequate terminology.

Most of what we know about Norse mythology comes from these Old Icelandic sources, which means not only a wealth of mythological information preserved by Christian monks but also a geographic and chronological limitation. Snorri Sturluson tries to offer us a very structured account, which was likely not the case in the Norse world. The poems are more reliable, yet also contradictory, or they contain vague references (we know that Loki and Heimdall once fought in the shape of seals but nothing more of it). Different stories would have circulated about the same myth, for example when Thor fishes for the world serpent, Jörmungandr: the poet Ulf Uggason alludes to Thor killing the serpent, while other sources insist on the creature escaping. Furthermore, almost nothing is preserved regarding rituals – Christian writers were very much focused on the ancient stories as a form of connecting to the past but describing heathen practices would have gone too far.

Even so, without Old Icelandic texts our knowledge about Norse mythology would be so much flimsier. What they recorded though were mythological narrations, beyond which we can uncover some of the mentalities, but how the religion was practiced is still out in the shadows. Belief and ritual seemed at any rate to extend way beyond just the worship of gods, in what we can deem magical thinking, with the natural and supernatural intricately bound together. There are mentions of landvættir (spirits of the land), as well as dysir or fylgjur, vague female or animal spirits. The poet Sigvat records a private rite in Sweden dedicated to the elusive elves (alfar), it would not be a stretch to imagine something similar happening in Iceland. Public rites on the other hand would have been vital for maintaining communities, and as the archaeology suggests most often held in the chieftain's hall (hóf). In the Eddas, we also find the term hörg for an altar, likely referring to an elevated platform on which a statue could be placed.

Boat graves were also retrieved from Iceland, such as the extensive burial from the West Fjords discovered in 1964. The boat contained the remains of 7 people, but it seems that originally only one person was buried and the other remains were collected from other graves and placed here. The inventory includes beads, a Mjölnir, two bronze bracelets, a fragment of a dirham, a bronze bell, two bone combs, and balance weights. Thor's hammer, the bell, and a piece of lead with an inlaid cross together – an interesting connection showing a rather fluid approach to religion or at least that Pagans did not have qualms about other religious objects. This reminds us of a character called Helgi the Lean, who in The Book of Settlements is said to have "believed in Christ but invoked Thor when it came to voyages and difficult times" (218).

Iceland's Conversion

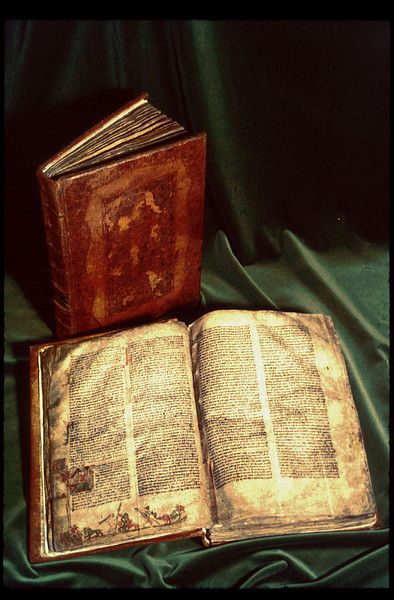

We find information about the Christian conversion of Iceland in several sources, such as the family and contemporary sagas, as well as historian Ari Thorgilsson's Íslendigabók (Book of Icelanders), annals or church writings, special sagas about churchmen, like those about the two saintly bishops Thorlak Thorhallsson and Jon Ogmundarson. The lives of the first bishops are treated in the Hungrvaka, a brief church history from the 1200s. A century later the lives of further bishops from Skálholt and Hólar were handed down, almost all writings in the vernacular.

The church texts do not really focus on the functioning of the early society, but on the establishment of the bishoprics, the role of priests, and generally conversion. We do know that a few settlers converted before Christianisation, and some were familiar with the new religion, no wonder given the number of cultural contacts the Vikings had with other populations, especially the Anglo-Saxons and Celts. Nevertheless, most of them followed the old ways.

We can reconstruct what happened based on the Book of Icelanders, the account of Ari the Learned, who wrote around 1120 and was brought up at a farm by Hall, a man who remembered being baptized by the missionary Thangbrand. There are other sources as well, like lost Latin sagas and references in family sagas like Njáls saga or Laxdæla saga. We know of an Icelander called Thorvald, baptized abroad, who brought with him a bishop from the Holy Roman Empire, but did not have any success. Stefnir's mission, sent by the king of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason (r. 995-1000), also failed, and he was even outlawed. Then Thangbrand arrived, an experienced missionary, who did manage to convert some Icelanders but also killed some people for having written offensive poetry about him, according to the saga of Njál at least. All in all, he did not convert the island either.

In the Book of Settlements (Landnámabók) we often read that some brought Christianity with them, but then returned to their ancestors' pagan practices:

[Aud] used to say prayers at Cross Hills; she had crosses erected there, for she'd been baptized and was a devout Christian. Her kinsmen later worshipped these hills, and then when sacrifices began a pagan temple was built there. They believed they would go into the hills when they died.

(97)

In other accounts, the power of Christianity would be decisive:

Bjarni promised to become a Christian, and afterward Hvit River changed its course and made a new channel where it flows now, so Bjarni gained possession of Lesser Tongue down to Grind and Solmundarhofdi.

(42)

The rituals involved in settling the lands were also diverse: many were worshippers of Thor, so they would throw the high-seat pillars with an image of Thor overboard and whenever they came ashore, they made their home, while others would bring along consecrated earth and an iron bell and settle after placing the posts of a church.

Despite the unsuccessful first attempts, the transition was quite smooth. The pagan majority had political motivations to accept the Christian minority; Iceland was growing increasingly dependent on trade with Norway, where Olaf Tryggvason resorted to forced conversion. The conversion of Norway in the written sources is linked to a succession of kings who were baptized abroad and brought their faith home, often accompanied by English clerics and bishops due to upbringing in England or in connection with Viking raids. These Christianising kings faced pagan opposition from Norwegian chieftains, as depicted in the Heimskringla, a 13th-century compilation of kings' sagas.

When Norway banned trade with Iceland on religious grounds, and the king even took some Icelanders hostage, Christians in Iceland felt encouraged to stand by their cause. Chieftains started to create parallel courts, raising the danger of a civil war. When skirmishes broke out at the Althing, the Icelandic mentality kicked in: mediation and arbitration – treating the conflict like a feud and searching for a way to settle. The law-speaker, Thorgeir, a chieftain from the northern quarter, was pagan but also had close ties with Christians, so both sides accepted his mediation. The people of Iceland accepted his decision because if the law were divided, then peace would, too. Chapter 7 of the Íslendingabók states quite clearly that everyone was to convert and be baptized, but people were allowed to sacrifice to their old gods as long as, well, essentially no one would snitch on them.

The conversion thus should be regarded as an official act; what you did on your farm was your own private decision, you could continue worshipping the old gods, just not at the official gatherings – there was no formal structure to verify if you adhered to Christianity at home. This means the process would have indeed been very gradual, especially until the law code Grágás was written, where we do find the canon law with all kinds of interdictions about the practice of magic (seiðr). Furthermore, without Christian scribes and scholars showing a deep interest in the pagan past, at least in mythological stories, we would know much less today about the Norse pantheon and the nine realms of Norse cosmology, despite all the problems works such as The Poetic and Prose Edda carry along. It was Christianity that brought literacy in the Latin tradition among the wealthier classes, without this development we cannot imagine the sagas. This was an oral society before. Committing information to writing is also reflected in the first census done on the island, initiated by bishop Gizurr.

The church in Iceland developed with very little interference from the Latin West. It was not the same dominant, overgrown institution as the medieval church in Western Europe. Economically speaking, the Icelandic church helped introduce a coherent system of taxation with the tithe, however, it did not reap a very significant revenue because most of it ended up with the chieftains. Icelandic priests themselves were not quite a separate class of society, but subjected to secular rules, and among their ranks, you could find influential farmers who wanted to keep their property. So the basic patterns of power and wealth were not fundamentally altered. The chieftains (gódar) built churches on their lands just like they did with pagan temples or just added a new building. At any rate, there was no separate jurisdiction for the clergy until the 12th century.

Iceland thus stands out during the conversion to Christianity compared to other Scandinavian countries in several key ways, primarily concerning the decision-making process and the immediate religious landscape following the formal acceptance of the new faith. Unlike Denmark, Norway, and Sweden, where the conversion process is closely tied to the actions of kings, Iceland's conversion is notably attributed to a decision made at the Althing. The parliamentary gathering decided that all Icelanders should be Christian and be baptized. This was a crucial difference from the continental Scandinavian countries, where royal authority played a more central role in the official adoption of Christianity.

Conclusion

The conversion in Iceland involved a significant compromise regarding religious practices. The Althing proclaimed that while everyone should be Christian and baptized, people would not be punished if they continued to sacrifice to the old gods in secret, eat horse meat, or expose unwanted children, even though these practices were against Christian law. This tolerance of private pagan practices alongside the official adoption of Christianity highlights a pragmatic approach to maintaining community cohesion. In contrast, the conversion narratives of the other Scandinavian kingdoms often emphasize the forceful suppression of paganism by missionary kings. However, there is a bit of nuance here as well, as bottom-up approaches can be noticed, albeit in less dramatic ways: burials oriented west-east, gradual replacement of cremation with burial, and pendants that could work both as crosses and Thor's hammers.

The decision at the Althing can be seen as a way for the Icelanders to bypass King Olaf's authority and his direct influence over their religious affairs, thus maintaining a degree of independence. They established their church and accepted Christianity in a manner that did not make them dependent on the Norwegian king. In the years following the conversion, Iceland also utilized wandering missionary bishops, who did not necessarily have strong ties to any particular ruler. This further supported Iceland's independence from the Norwegian crown in religious matters. Local magnates also played a role by travelling to the continent to be consecrated as bishops, ensuring the continuation of the church structure under the authority of the Archbishop of Hamburg-Bremen, at least initially, rather than being solely reliant on Norwegian clergy.

In conclusion, while this whole story of Icelandic conversion might strike as odd, given the way Icelanders usually settled disputes, with procedures, compromises, and resolutions, it fits the general picture. By reaching this compromise, Icelanders opened up to Western Europe while at the same time maintaining a strong connection to the past.