The act of voluntary death was never condemned in antiquity. In fact, The English word "suicide" comes from the Latin for "self-slaying." The reason for a voluntary death had to be one that was honorable and necessary to remove any element of its opposite, shame. A noble death was based on the important element of choice.

Men were judged in both their private and public lives on the basis of arete. Arete was the goddess of virtue and knowledge. Applied to a person, the term meant excellence, virtue, and valor, and contributed to the twin sociological concepts of honor and shame. Honor was an element of one's worth to both one's family and the community, their private life, as well as their public persona.

The idea that people died and went to heaven was relatively late. The land of the dead, Hades in Greek and Roman mythology, was initially a neutral area. Later concepts developed special areas for the virtuous and wicked in the land of the dead.

Hero Cults

Ancient Greece had hero cults. The legendary heroes of Greek mythology were the offspring of a god or goddess or the result of sexual intercourse between humans and the divine. A prime example was Herakles/Hercules. Heroes were rewarded for their great deeds by being in the higher realms in Hades. The concept was described as apotheosis (deification); one would reach the levels of the divine and thus be worthy of worship and honor. People made pilgrimages to the tombs of the heroes.

At the same time, each city-state or city claimed foundation myths, that a god or demigod had established their community. Based on the sociological concept of patron/client, sacrifices were offered by the community to the patron god/goddess in return for their mediation for benefits and protection of the community.

The Elysian Fields was reserved for the heroes. Homer and Hesiod placed it on the western edge of the Earth, bordering Oceanus, and Hesiod also referred to it as the Blessed Isles. It was a utopia where the honored dead led a happy and carefree existence and indulged in their favorite pastimes such as music or athletics.

Homer

The 8th-century BCE poet, Homer, in his major epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, recounted the 10th year of the war between Greece and Troy and then the wanderings of Odysseus and his attempts to return home after Troy fell to the Greeks. The Iliad and the Odyssey were updated over the centuries by Greek dramatists.

The greatest hero of the Trojan War, Achilles, was the son of the Greek king Peleus and Thetis, a sea nymph goddess. At Zeus' direction, Thetis dipped him in the River Styx to imbue him with immortality, holding him by his heel, which remained vulnerable. Achilles was a champion warrior, utilized by some city-states in individual combat against their enemies. King Agamemnon rallied the Greeks to go to war over the abduction of his brother Menelaus' wife, Helen of Troy, by a prince of Troy, Paris. Achilles consulted his mother on whether he should join them. She told him that he could stay home, marry, and have offspring and a normal life, and die of old age. If he went to Troy, however, he would die young, but be remembered forever. He chose to go to Troy. In the Iliad, his death is predicted, but the arrow shot by Paris that penetrated his susceptible heel is in the later Odyssey.

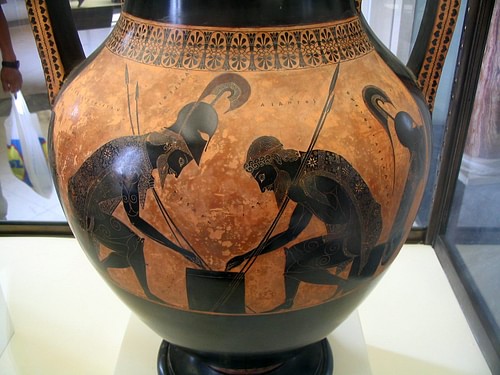

Ajax was another great warrior at Troy. After the death of Achilles, Ajax and Odysseus competed for Achilles' armor. The armor had magical properties because it had been forged in Mount Olympus by Hephaestus. More details were added in Sophocles' Greek tragedy Ajax, where a group of judges deemed Odysseus the winner. Upset by the decision, Ajax fell under the spell of Athena, lost his mind, and slaughtered a flock of sheep that he believed were warriors. When he woke up, he was ashamed and killed himself as the means by which to recover his honor.

Greek dramatists added details to Homer. Not described in the Iliad, Euripides (480-406 BCE) wrote the tragic play Iphigenia in Aulis. Iphigenia was the daughter of Agamemnon. While out hunting on his way to gather the fleet for Troy, Agamemnon killed one of the sacred stags of the goddess Artemis, who held back the winds for the ships to sail. The seer Calchas informed Agamemnon that he must sacrifice his daughter to appease the goddess.

At first, Iphigenia believed that her father had summoned her for her marriage, but she then learned that she was to die. Once she realized what was happening she accepted her fate, in this sense restoring the honor of her father:

Father, as you bid me, I am here. I give my body, freely on behalf of my country, for all the land of Greece. Lead me to the altar. There, if that is the gods' will, sacrifice me. May this gift from me bring you success. May you win the crown of victory and win thereafter a glorious homecoming. (lines 1553-1558)

At her execution, the crowd proclaimed: "We the Greek army and King … offer this sacrifice of a pure virgin" (lines 1570-1575). Suddenly there was a miracle. "Everyone had heard the sound of the knife—but no one saw where she disappeared to" (lines 1582-1583). There "on the ground lay a deer," sent by Artemis as a substitute of appeasement (line 1587).

As something of value, the greatest sacrifice was that of life. At the same time, Iphigenia's sacrifice as a virgin meant that she would have no descendants to remember her. The memory would have to come from the community in retelling her story. The result of a victory after her death aligned her sacrifice with the concept of military victory or patriotism. A noble death benefited the entire community and enhanced its reputation of defending the dictates of the gods.

The Trial & Death of Socrates

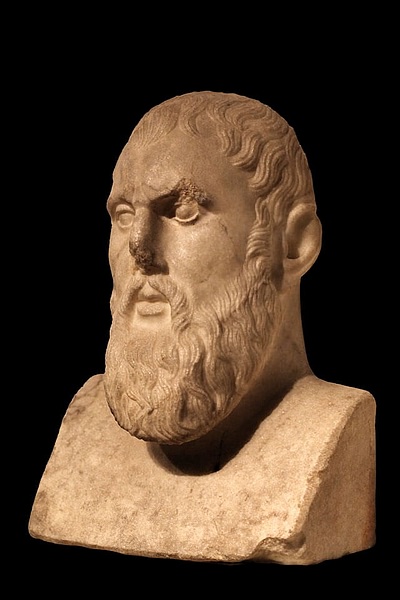

Founder of the Academy in Athens, Plato (428-348 BCE) is one of the most important philosophers in Western history. He was a pupil of Socrates, whose teachings only survive in the writings of Plato. Socrates was tried by a court in Athens for impiety, the corruption of the youth of Athens (with different views of the gods), as well as criticism of the Greek government. An Athenian court convicted him with the resulting penalty of death (399 BCE). In Plato's Apology and elsewhere, he summarized Socrates' views of death and the afterlife:

- The study of philosophy is the study of the process of dying and being dead. The body and material existence impede the pursuit of truth. The soul is trapped in a physical body and involved in evil, and can only escape after death. All should welcome death in order to attain the greatest blessings. Death is either a virtual nothingness or a change in the status of the soul and a migration from this place to the afterlife.

- However, humans are the possessions of the gods who gave us life, and we are in their care. One should not take one's life unless there was some sign from the gods (anangke). Only then would this indicate their approval. According to Plato, Socrates claimed to have heard a divine voice beginning when he was a child that turned him away from anything evil.

Socrates' friends planned for his escape from the city, but he refused to go. He claimed that he could argue his way out of his predicament, but doing so would be demeaning. When a man acts, he acts for the right reasons or the wrong reasons. The sum of his actions is far more important than preserving his life. Socrates berated his companions:

For according to your argument [of compromising to save one's life] the demigods would be bad who died at Troy, including the son of Thetis [Achilles] who so despised danger, in comparison with enduring any disgrace, that when his mother (and she was a goddess) said to him, as he was eager to slay Hector, something like this, "I believe, my son, if you avenge the death of your friend Patroclus and kill Hector, you yourself shall die; for straightway, after Hector, is death appointed unto you". When Achilles heard this, he made light of death and danger, and feared much more to live as a coward and not to avenge his friend, and said, "Straightway may I die, after doing vengeance upon the wrongdoer, that I may not stay here, jeered at beside the curved ships, a burden of the earth."

(Apology, 28c-28d)

As the ultimate model of the noble death, Socrates personified choice in self-sacrifice, a choice that was based on reason. While maintaining the virtues of arete and courage, he articulated the concept of self-sacrifice as dying for a principle. A principle is a fundamental truth or proposition that serves as the foundation for a system of belief or behavior following a chain of reasoning. We begin to have the concept of dying for a cause that supersedes the individual.

In further writings by Plato, voluntary death could only be justified for honorable reasons:

- if one is ordered to do so by the polis, an order that, if valid, should be carried out

- if one has encountered devastating misfortune

- if one is faced with intolerable shame

Mundane, ignominious reasons were not legitimate, such as getting out of military duty or avoiding financial ruination. But humans also had responsibilities to the city-state. Love, sex, and marriage in ancient Greece came with the religious duty to produce children for the survival of the generations. Anyone who took their own life for dishonorable reasons should be denied a tomb in communal areas of cemeteries. The tombs of such people were set in isolated districts beyond the city's borders with no tombstone, name, or memory.

Stoicism

Another popular school of Greek philosophy was founded by Zeno of Citium (336-265 BCE) and was named after the stoa (an open colonnade) where he taught in Athens. For Stoics, deeds and behavior were what mattered, not particularly thoughts, and all behavior had to be in harmony with reason and nature. Because the universe was subject to natural laws, one must accept everything that happens with equanimity.

Humans have access to divine reason through their intellect, recognizing that there is a divine plan, often deemed to be fate, which the good Stoic learns to accept; it cannot be changed by anything we think or do. This acceptance is accomplished through a disciplined lifestyle of never letting emotions rule one's life, known as apatheia. In modern jargon, a Stoic should "grin and bear it," being impervious to both pain and pleasure. One exercised one's freedom of will in relation to nature or fate.

The Maccabee Revolt

The idea of a noble death influenced the Jewish people who rose against the forced dictates of the Greek conquest of Israel under Antiochus Epiphanes in what is known as the Maccabean Revolt (167-160 BCE). Those who died for refusing to deny their Judaism introduced the idea of a martyr (Greek: "witness"), testifying or "witnessing" for their faith. As such, they included the concept of patriotism in that they were vicariously atoning, suffering for the sins of the nation. Their reward for the sacrifice of their lives was being raised up by God (resurrection) to heaven.

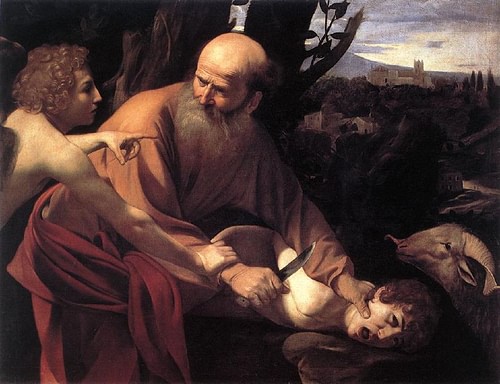

In the history of Israel described in the Jewish scriptures beginning with the book of Genesis, the later concept of martyrdom is absent. However, in the Bar-Kochba Revolt (132-136 CE), Jews were persecuted and tortured for their faith. The later rabbis of the 2nd to 5th centuries CE read back the concept of martyr for earlier characters. For example, Isaac was now deemed a martyr for his willingness to be sacrificed by his father Abraham.

In what became Rabbinic Judaism, all life is considered sacred, a gift from God. It should not be risked for mundane reasons. Through torture, if a Jewish person is ordered to eat pork, they should do it. Eating pork cannot damage one's soul. But certain essentials cannot be transgressed. These come under the category of the concept of ha-shem ("the name"). Originally, the Hebrew concept of blasphemy was a charge against utilizing the name of the God of Israel in an oath and then breaking it, disrespecting God, or committing idolatry. This brought dishonor, shame, and denigration to the name of God and his precepts. Martyrs who resisted and refused to dishonor the name were titled kaddosh ("holy one"). Being willing to die for the sanctification of the name qualifies one as a martyr. Any Jew who acquiesced to idolatry under torture would be denied the status of martyr and a place in the world to come when God manifests his kingdom.

The Noble Death in Ancient Rome

Rome absorbed much of the mythology of Greece, aligning ancient Italian gods with the similar traits of the Olympians. However, Rome was much more interested in their foundation stories, the first ancestors, and families with stories that emphasized the virtues of Roman society.

Every Roman citizen had the right and privilege to commit suicide. The reasons followed the precepts of Platonism and Stoicism, and the restoration of honor over shame. In Rome, this included women. The model for women was the story of Lucretia. One of her husband's political rivals visited her while her husband was away. He tried to seduce her, but she resisted, and he raped her. He then told everyone that she had cooperated. When her husband came home, Lucretia invited his friends to a dinner, told the real story, and then stabbed herself to death. Even though it was a lie, her reputation and honor had been damaged and had to be restored. Lucretia became the model for all proper behavior in accordance with the role of women in the Roman world.

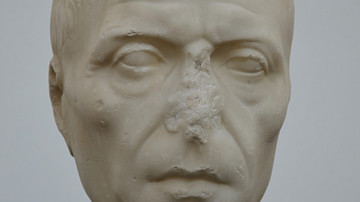

One of the most famous suicides in the late Roman Republic was the Stoic, Cato the Younger (95-46 BCE). He was one of the most influential Senators in opposition to Julius Caesar (100-44 BCE). When Caesar defeated the last of the Republic forces in Utica, North Africa, he offered amnesty to Cato, as he did for many of his former enemies.

At a dinner with friends, the conversation was a discussion of Plato's description of the death of Socrates, with Cato's friends trying to convince him not to commit suicide. Cato then stabbed himself and pulled out his stomach and organs. His friends rushed for a doctor who sewed him up. But Cato tore off the bandages and the sutures, pulled out his organs again, and died. In the tradition of Socrates, his life's work in maintaining the Roman Republic against Caesar would have meant nothing, and he would be deemed hypocritical unless he died.

There was also another motivation for suicide in Rome. Anyone accused of treason against the state was condemned to public execution, and their wealth and estates were seized for the treasury. However, nobles had the option of avoiding this humiliating event by committing suicide first. If a patrician committed suicide, the family would not be ruined, and the accused could be removed from the shame of his crime by carrying out his duty for the welfare of his descendants.

Early Christianity

Paul the Apostle (writing in the 50s and 60s), was the first to articulate the death of Jesus Christ as atonement for the sin of Adam in the Garden of Eden. Adam's sin of disobedience resulted in the loss of immortality; as, according to the Bible, we all descend from Adam, this is why we all die. Adam's sin brought death, but Jesus' death brought life. The formula for this concept where Jesus died for our sins, and Jesus took on the sins of the world, became a pillar of Christianity. Technically, this was not true; sin continued in the world. But believers could now achieve a continued existence in the afterlife in heaven. The later gospel stories of the trial and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth became the template for all Christians. This was not suicide, but the fulfilling of his destiny, why God had sent him to earth in the form of man. Throughout the gospels, Jesus 'predicts' his ultimate fate, choosing to go to Jerusalem where he knew he would die.

Augustine of Hippo (354-430) would be the first Christian to declare suicide a sin. He did so against a rival sect of Christians in North Africa, the Donatists. Donatist monks were deliberately trashing pagan shrines, hoping they would be arrested so that they could achieve martyrdom. Some set themselves on fire or threw themselves off of cliffs. Augustine demeaned these rival Christians who should not be elevated as martyrs. He declared suicide as a sin that can never be forgiven as it upended the goodness of God's creation. He used the example of Judas. Judas could have been forgiven, but his suicide was why he will forever remain in hell. Hence, no Christian who deliberately sought his own death could receive the official status and title of martyr. And hence, no Christian who committed suicide could ever go to heaven. During the Middle Ages, suicides were denied the last rites by the medieval church and forbidden burial in church cemeteries.