Ancient views of the afterlife are reflected in literature, tomb inscriptions, and grave goods. Then, as now, a belief in another stage of existence after death was a shared belief by all ancient societies. Initially, the Greco-Roman Hades contained all the dead. Over time, the dead became distinguished by the virtuous and the wicked and were assigned different areas in the land of the dead.

Roman tombstone inscriptions demonstrate an absence of the often esoteric views of the schools of philosophy and the elevation of the soul after death. Philosophical reflections are rare. One of the shortest tombstone inscriptions summarizes what may have been an Epicurean concept. Epicureans believed in the existence of the gods but rejected their interference in human affairs. It was up to humans to avoid pain and suffering and focus on the good things of life, not worrying about the afterlife: "Non fui, fui, non sum, non curo" ("I was not; I was, I am not; I care not").

There are no references to the chthonic powers (the avenging divine beings such as Nemesis and the harpies), levels of Hades described by Plato (l. 424/423 to 348/347 BCE), or the walled cities in Hades described in Virgil's Aeneid. When references do appear, it is expressed more as hope than as a firm belief in the details of what awaits.

Education in the Ancient World

Historians often estimate the level of Roman education at 1-5%, coming from the upper classes. This is what we term formal education, which consisted of Romanized versions of the Greek mythology, Homer's tales, classical Greek drama, Roman histories, and various schools of Roman and Greek philosophy. An element for the elite, formal education required leisure and money, resources not available to the rest of the population. The upper classes utilized pedagogues (tutors), often educated slaves in philosophy, who lived with the family and were honored members of the household. Many cities had public libraries with borrowing privileges for the upper classes.

However, education in this sense was different from basic literacy. Basic education for girls in ancient Rome was the same as for boys; they were taught the basics of reading and writing, either in the home or in organized schools. This included some tales of Homer and some history of Rome. Especially among the business classes and trades, some literacy was required, as well as the essentials of mathematics, simply to do business. The dozens of examples of graffiti (many having to do with campaign promises during elections) would have been pointless if most of the public could not read.

The majority of Romans were exposed to what we term "classical literature" through the dozens of Greek tragedy and comedy performances offered during the religious festivals. Politicians dominated the Roman forum with speeches that referred to traditions. Then (as now), public trials were popular entertainment where advocates educated in Roman law couched their arguments with references to both traditions and myths.

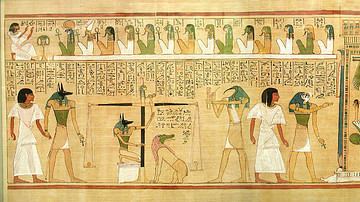

In the literary versions of Hades, Minos, Rhadamanthus, and Aeacus were judges of the dead in the afterlife. According to their deeds in life, the dead were assigned various places in Hades. All Romans knew about this through the gladiator games. At the end of a bout, characters dressed as Minos and Rhadamanthus tested the loser with hot irons to make sure he was dead and not faking. But we find no reference to any judgment in the afterlife. Average Romans must have known various elements of Hades, but they did not produce a comparable equivalent body of literature on the details of what happened after death.

Public Scribes

Ancient Rome had public scribes, many of whom were state slaves, whose responsibilities included the recording of formal, important elements of Roman society. They wrote down the minutes of the Roman Senate, magistrates' dicta, the ruling of priestly colleges, and the publication of laws passed by the Plebeian assemblies. Dozens of scribal clerks worked for advocates (lawyers), writing up trial transcripts. They derived additional income by offering their services for property transactions and the privilege and obligation of every Roman citizen to make a will.

The translation of the Latin from the Greek amanuensis, servus a manu, ("a slave with secretarial duties") gives us the word "manuscript." In the New Testament, in some of the letters of Paul the Apostle to the Gentiles, Paul dictated to his amanuensis, who also signed some of them.

Roman Tombstones

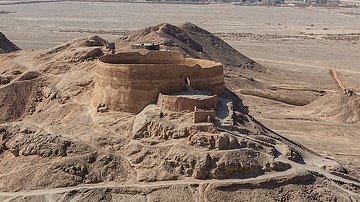

Tombstones began as cippi, stone grave altars inherited from the Etruscans, designating zoned cemeteries but also adapted for sacred zones of temples and shrines. Grave altars were distinct from other altars as there were no blood sacrifices attached to them.

Tombstones were vitally important. Literally carved in stone, this was the way one would be remembered – a legacy to pass on from the traditions of one's ancestors to one's descendants. A tombstone carving was an epitaph, from the Old French epitaphe, via Latin from Greek epitaphion ("funeral oration"), ephitaphios ("over or upon tomb"). There was an entire industry of specialist tombstone carvers available for this service. Tombstones that quoted famous poets or lines from Roman and Greek literature most likely came from the hand of a more educated carver.

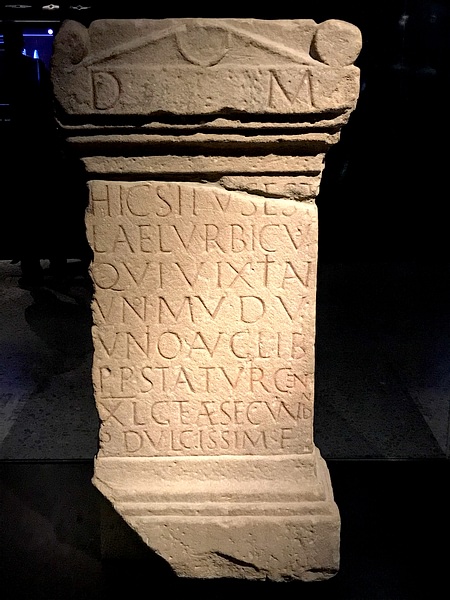

Tombstone inscriptions were addressed to the manes, the spirits of the dead, who were understood to still be present in or around the tomb. Only indirectly related to any judgment, manes, dead ancestors, were understood to have achieved a pleasant afterlife and served as guardian beings for the living. Manes was abbreviated to DM, "Dis Minibus" ("to the spirits of the departed"). Tombstones are often difficult to translate as they contain many abbreviations of clans and family names. This reflected the ability to pay the tomb carver who set the rates for the number of words. RIP ("requiescat in pace" or "rest in peace") only came into Christian use in the 8th century.

It is from tombstone inscriptions that we learn details of the lives of everyday Romans. The tombstones list occupations, military rank, marriage partners and children, and the dead person's status as free, freedman/freedwoman, or slave. They also express an attitude toward the inevitability of death and dying:

Albia Hargula, freedwoman of Albia: lived 56 years. Chaste she was and the soul of honor. If the dead have any sense at all, may her bones which lie here rest in perfect peace.

(CIL 6.11357)

Tombstones also promoted the ideals of social conventions, especially for women. The role of women in the Roman world was to marry, bear children, and run a productive household. A productive household included a loom for the wife to weave everyone's clothes herself. Weaving was allegorical and symbolic of women's role to weave together the elements of life. Whether a woman actually did this or not, the epitaph would often begin with "I kept the house, and I worked in wool." This was also a description of how she honored her husband by being obedient to him in all things. Tombstones had images of a reunion of a man and wife if one had predeceased the other. They were sometimes shown holding hands.

Rather than appealing to the gods for a safe journey and a pleasant afterlife, many tombstone inscriptions were addressed to the living, informing the living how the deceased wanted to be remembered. Rome promoted a concept known as mos maiorum, "the custom of the ancestors," an unwritten code of social norms outlining family roles, public, and political life. All levels of society were duty-bound to climb the ladder, to move up in the world. The high rate of divorce in ancient Rome was not so much driven by moral considerations (although that was present) but by arranging new marriages as political power factions changed, from one dominant ruling family to another.

By my good conduct I heaped the virtues on the virtues of my clan; I began a family and sought to equal the exploits of my father. I upheld the praise of my ancestors, so that they are glad that I was created of their line. My honors have ennobled my stock.

(CIL 1².15)

This applied to slaves as well; Rome allowed for the manumission of slaves, who would become freedmen and freedwomen. Freed slaves had the right to marry, have children, and become lawful citizens. It may appear strange to us that someone would list their earlier life as a slave on their tombstones, but there was no shame in this; it emphasized that they had done their duty as good citizens for the benefit of Rome. Carved reliefs on the tombstones of freed slaves showed them dressed in a toga, the symbol of freedom and higher status.

Everyone Has the Same Fate

May tombstones opened by getting the attention of anyone passing by with lines like "Wayfarer, stop here!" Others were more poignant in their appeal:

Young man, though you are in a hurry, this little stone asks you to look at it, and then to read the message with which it is inscribed. Here lie the bones of Lucius Maecius Plilotimus the hardware man. I wanted you to know this. Farewell.

(CIL 1².1209)

Several inscriptions reminded the living that everyone is going to end up in the land of the dead:

Marcus Statius Chilo, freedman of Marcus, lies here. Ah! Weary traveler, you there who are passing by me, though you may walk as along as you like, yet here's the place you must come to.

(CIL 1².2138)

High infant mortality rates were a shared anxiety in family planning in the ancient world. Beyond miscarriages and premature (still)births, childhood in ancient Rome was threatened with a range of illnesses. Memorials for those who died young, the children, usually expressed the grief and bitterness of the parents against Fortune or the Fates. A great grief is that the young had no chance to leave a legacy, one of the most important concepts for a Roman:

Great virtues and great wisdom holds this stone with tender age; whose life but not his honor fell short of honors; he that lies here was never outdone in virtue; 20 years of age to burial-places he was entrusted. This, lest you ask why honors none to him were ever entrusted.

(CIL 1².11)

Sacred to the spirits of the dead; to Lucius Valerius, an infant, who was taken away unexpectedly. He was born during the sixth hour of the night, a sign of fate not yet clear. He lived 71 days. He died at the sixth hour of the night. I hope that your family, oh reader, may be happy.

(CIL 6.28044)

Despite popular views, Romans mourned the death of a daughter as much as they mourned the death of a son:

To Vettia Chryses, daughter of Gaius; I ask you passerby not to walk over the remains of the miserable infant buried here in the ground. She will be mourned whenever people remember how her youth was taken from her. She was born for no better reason other than that she now undeservedly lies here. Her bones have become ashes and the daughter can no longer talk to her parents.

(CIL 6.28695)

Some things do not change over time; dogs in the ancient world were just as dear to their owners as they are today:

My eyes were wet with tears, our little dog, when I bore you [to the grave]. So, Patricus, never again shall you give me a thousand kisses. Never can you be contentedly in my lap. In sadness, I buried you, as you deserve. In a resting place of marble, I have put you for all time by the side of my shade. In your qualities, you were sagacious, like a human being. Ah, what a loved companion we have lost!

(Abbott, 187-188)