The siege of Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) began during Operation Barbarossa, the invasion of the USSR launched by the leader of Nazi Germany, Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), during the Second World War (1939-45). The siege or blockade lasted from 8 September 1941 to 27 January 1944 and became a symbol of Soviet defiance against the Axis invaders.

Hitler was convinced that if he could capture the two great Soviet cities of Moscow and Leningrad, then the USSR would collapse. The siege of Leningrad, conceived as a deliberate strategy to starve a city with a population of around 2.5 million, led to one million civilian deaths. The city withstood the blockade thanks to supplies coming in by truck across frozen Lake Ladoga in winter and by boat in the warmer months. Red Army counteroffensives, particularly in the winter months, sapped the strength of the invaders until Leningrad was finally liberated in January 1944.

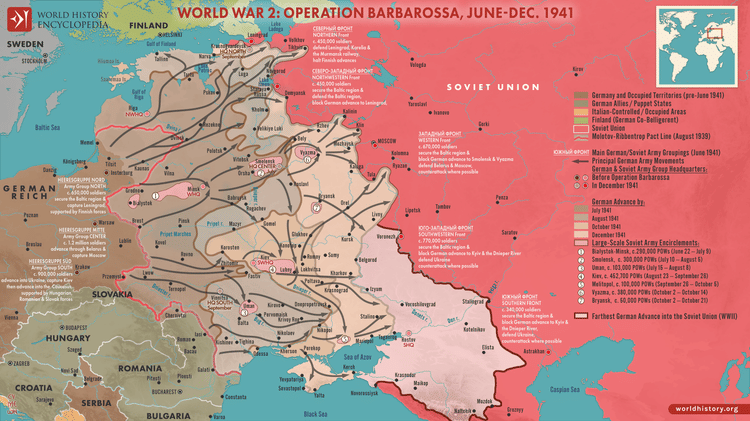

Operation Barbarossa

Adolf Hitler was confident, after swift Axis victories in the Low Countries and France in 1940, that he could make even greater gains in territory and resources by attacking the USSR. The Nazi-Soviet Pact, signed between Germany and the USSR in August 1939, was shown to be a mere agreement of convenience until Hitler was ready to wage war in the east. Hitler, as he had always promised, was determined to find Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper.

Operation Barbarossa, the code name for the attack on the USSR, was launched on 22 June 1941. The overall objective was to smash the USSR's Red Army and take control of several key cities, thus gaining access to natural resources from the Baltic to the Black Sea. The invading force, made up of German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men in 153 divisions, 3,600 tanks, and 2,700 aircraft (Dear, 86). The overall commander was Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). The invading force was divided into three massive army groups. Army Group North (AGN), commanded by Field Marshal Wilhelm Ritter von Leeb (1876-1956), consisted of around 500,000 men. Unlike the other two army groups, AGN found that the swampy ground around its primary target of Leningrad meant the Blitzkrieg ('lightning war') tactics of using fast-moving armoured, air, and infantry troops to attack on a narrow front could not be used as effectively as they were in the wide open spaces further south.

Objective Leningrad

Leningrad was founded as Saint Petersburg in 1703 and had served as the capital of Russia from 1712 until the Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917. From 1914, the city was known as Petrograd, and from 1924 (until 1991), as Leningrad. The city was the cradle of Bolshevism but made more practical contributions to the Soviet war effort by producing around 10% of the country's entire industrial output. In addition, the USSR's Baltic Fleet was based at nearby Kronstadt. One plus for the Axis invaders was that allied Finnish forces under the command of Marshal Carl Mannerheim (1867-1951) were able to participate in the campaign and advance on Leningrad from the north. Leeb hoped, then, to surround the Soviet city and force its surrender. Another advantage for the invaders was that Leningrad was "always entirely dependent on outside sources for food, coal, and oil" (Dear, 536).

Hitler had convinced himself that if Moscow and Leningrad fell, then the Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), would surrender, or the Soviet regime would collapse and descend into chaos. Control of this part of the USSR would also allow the Finnish Army to play a part further south. Army Group Centre was tasked with taking Moscow, and so Leningrad also had to be taken to protect the northern flank of this central army as it thrust deep into Soviet territory. Finally, nickel mines to the east of Leningrad could be a valuable addition to the raw materials needed for Hitler's war machine.

The Defenders

As the Axis army approached, there was only a very limited evacuation of Leningrad. Priceless artworks of the Hermitage Museum were secretly removed from the city. The Soviet commanders of the wider Leningrad Front, as it became known, were Markian Mikhaylovich Popov, then Georgy Zhukov (Sep-Oct 1941), Ivan Fedyuninsky (Oct 1941), Mikhail Khozin (Oct 1941 to Jun 1942), and finally, Leonid Govorov (Jun 1942 to July 1945). The man initially in charge of Leningrad's defence was Marshal Kliment Voroshilov (1881-1969). Voroshilov, an incompetent commander but a staunch supporter of Stalin, had not fared at all well in the disastrous Winter War with Finland (1939-40), and he lost the Leningrad command in September 1941. The four Soviet armies at Leningrad totalled around 300,000 men (Forczyk, 36), to which were added militia units and workers' battalions for internal security (made up of 40,000 men and women). It was Zhukov who passed the order that anyone who withdrew from the defences without written permission would be shot.

The city's defence was boosted by the naval guns of the Baltic Fleet, which included two battleships, Marat and October Revolution, and by the fleet's rifle brigades. The Axis air force had dropped thousands of mines to block the fleet from leaving port, but the ships were, in any case, chronically short of fuel. Although attacked from the air, the fleet was relatively well protected by formidable anti-aircraft batteries. Finally, the fleet on Lake Lagoda behind Leningrad included a dozen vessels and 80 barges, which proved invaluable in supplying the city in the warmer months of the year.

Cutting Off the City

The first move by the invaders came on 8 July when they cut off Leningrad's eastward land connection by capturing the old fortress at Shlisselburg. An early setback for Leeb was that the Finnish army refused to advance beyond the River Svir since this area had not been Finnish territory prior to the Soviet invasion of Finland in 1939. The decision left the Finns a full 26 miles (40 km) from Leningrad, but they at least had cut off the land strip north of Leningrad, the Karelian Isthmus between the Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga.

The advancing Axis forces of Army Group North planned to seal off Leningrad in the south and cut off the vital Leningrad-Moscow railway line in the east. In order to effectively blockade Leningrad, Leeb was obliged to make several large-scale manoeuvres. He arranged his forces on two fronts, one based on the forts of Oranienbaum and the other south but close enough to Leningrad so that the city was within range of artillery fire, although shortages of ammunition typically meant shelling was intermittent and not particularly damaging. No part of the city was out of the range of the Axis shells during the blockade. The Axis shelling began on 4 September. A few days later, Axis bombers began to repeatedly strike the city.

By 8 September, Leeb controlled the southern shore of Lake Ladoga, an area he called ‘the bottleneck'. Hitler then ordered Leeb to close the gap left by the non-advancing Finns. Accordingly, in mid-October, Leeb moved troops eastwards to try and get around Lake Ladoga. The Axis tanks had already suffered heavy losses, but on 8 November, Tikhvin was taken, which was an important railway hub. Red Army reinforcements pushed back the Axis advance, and Leeb, with a severely weakened force in desperate need of supplies, was obliged to withdraw on 8 December to the west of the River Volkhov. Crucially, then, after all this manoeuvring, Leningrad could still be supplied from the east across Lake Ladoga. The Axis plan to completely encircle and then take Leningrad in a matter of weeks was already in tatters. Leeb simply did not have enough troops to perform gigantic encircling movements on a well entrenched Red Army, a situation made worse when Hitler decided to withdraw the 4th Panzer Group and most of the air support to reinforce Army Group Centre's push to Moscow. Even worse, the first signs of what would turn out to be an unusually cold winter had arrived early.

Hitler changed his initial plan to capture the city to a much simpler one of total destruction in September 1941. The Führer issued a directive that "ordered the city and its whole population to be obliterated by bombing, shelling, starvation, and disease and prohibited a surrender from being accepted, were one to be offered" (Dear, 536). The battle, then, settled down to siege mode with both sides digging in for the long term, building extensive trench defences with regular strongpoints, mines, and hundreds of miles of barbed wire. Both sides settled for only occasional pushes against the enemy's positions, mostly using infantry since the marshy ground was unsuitable for tank manoeuvres.

A City Under Siege

The people of Leningrad were already suffering as the first shelling began. Food was rationed, and by November, there were further reductions, almost to starvation level. There was also a chronic fuel shortage. Supplies could come in across Lake Ladoga – by boat in summer and across its frozen surface in winter – but only around two-thirds of the city's daily requirements could be met this way. Supplies coming in through this route, which was around 220 miles (350 km) long, had to face the hazards of Axis bombers and artillery fire. From 1942, the ice road was better protected by Soviet anti-aircraft batteries. Even front line troops suffered rationing, as little as 500 grams (17.5 oz) of food each per day in the winter of '41/2.

The trucks and barges that brought in supplies were able to take people out on the return trip. The Soviet figure for evacuees brought out in this way eventually came to 850,000. More could have been shipped out, but Leningrad's Communist Party chief, Andrei Zhdanov (1896-1948), was afraid that Stalin would see such a move as defeatist and, as he had in other cases, order Zhdanov shot.

Fuel and electricity were provided to the besieged city using pipes and cables laid on the bed of Lake Ladoga, but most civilians in the siege's first winter had neither heating nor light. The Axis besiegers began to bring surface vessels and submarines to patrol the lake in the late summer of 1943 and bombard supply lines going in and out of the city. The situation improved when the Soviets won a corridor to Leningrad along the southern shore of the lake and then built a rail link to the besieged city.

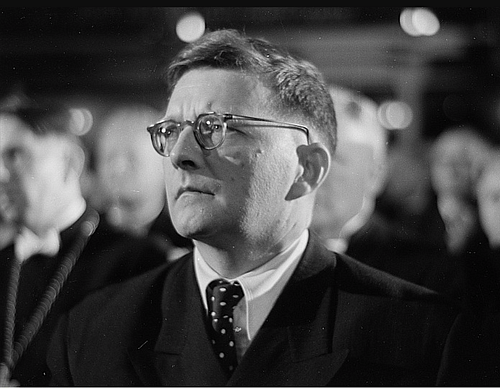

Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975), the famous Russian composer, was born in the city, and he served as a volunteer firefighter during the siege (but was subsequently evacuated). Shostakovich's new Seventh Symphony, which contained a recurring "invasion" theme meant to conjure up images of staunch Soviet resistance, became widely known as ‘the Leningrad' symphony. The score was air-dropped into the besieged city to be played by the surviving members of its most prestigious orchestra, the performance relayed through the streets via loudspeakers. Music was not the only area where the people of Leningrad attempted to continue their interests despite the privations of the siege. Public libraries remained open and popular throughout the city.

Ordinary citizens were stoical in resistance, as here told by a Leningrad housewife, Olga Rybakova:

Well, naturally, we felt very depressed when we heard about the suburbs of our city being taken by fascist troops. But still we thought and we hoped that all these defeats would be only temporary, just as they were a hundred and forty years ago when we had the invasion of Napoleon troops.

The most terrible time was December 1941 because I think until August we had commercial shops so we could buy something and it was a great help for us. We could even buy caviare, but then the commercial shops were closed. The blockade began…in November it began to be cold and the rations were shortened, became less and less food, and the end of November, December and January were most tragical times. Firstly, it was cold – minus forty – then the famine, the hunger began to be felt and people began to starve and die…Most deaths came...the end of February and March. When I went to the shops to receive the ration for my family and for some friends living in my house, when I went on the way there I found I had to pass dead bodies…

(Holmes, 282-3)

The 1942 Offensive

As a new year arrived, Leningrad continued to resist, but in January 1942, 4,000 people were dying every day. A Red Army offensive was launched against the Axis positions between Lake Ladoga and Lake Ilmen on 7 January 1942. It was hoped this attack would create a new front, the Volkhov front, and relieve the pressure on Leningrad. The offensive was commanded by Marshal Kirill Meretskov (1897-1968), and he sent a large force under General Andrey Vlasov (1900-1946) to strike deep into the enemy-held territory. The Red Army surprised the enemy with its skill at fighting in extreme temperatures and its innovative use of troop-carrying sledges powered by aircraft engines, particularly on frozen Lake Ilmen.

The Soviet offensive made significant progress through the winter, but from the spring of 1942, it faced a heavily reinforced enemy. The Axis forces hit back and eventually captured Vlasov and his now-isolated Red Army in June-July, largely because Stalin had refused to sanction a retreat. The Red Army lost 130,000 men in this encirclement. The victory came at a high cost to the Axis force, which suffered some 60,000 killed or captured. Meretskov thereafter concentrated on keeping open the fragile supply lines to Leningrad.

At the end of August, a large Axis offensive was launched under the command of Field Marshal Erich von Manstein (1887-1973). Manstein was something of a specialist at shaking up stalemate positions on the Eastern Front, and he got closer than ever to Leningrad, but the city's outer defences still held. Hundreds of thousands of militia and ordinary citizens of Leningrad – men, women, and children – had been tasked with bulking up those defences. In the end, Leningrad benefitted from around 550 miles (880 km) of anti-tank ditches and some 5000 earth bunkers.

Once electricity was restored, the city's armaments factories kept up their production as women, in particular, were enrolled in this work while the men fought at the front. Even tanks were produced, but such were the limitations of materials, many were sent directly to the front without the benefit of camouflage paint. Civilians were also busy that summer planting any plots of earth they could find with seeds to provide vegetables for the next winter. At the same time, as the fate of the city still hung in the balance, many buildings were mined in case the invaders fought their way in.

In September 1942, respite of sorts came. Hitler changed his mind, and, thinking a battle for Leningrad would be too costly, he ordered the commander of Army Group North, Georg von Küchler (1881-1968) – who had taken over from the unwell Leeb the previous January – to instead starve the city into submission. Hitler intended to remove Leningrad from the map, and so it meant nothing to him if the population starved to death.

The 1943-4 Campaigns

In January 1943, Marshal Zhukov returned and masterminded another offensive, Operation Spark, which eventually created a safe corridor south of Lake Ladoga. A second Red Army offensive, this one led by General Govorov, simultaneously attacked the other side of ‘the bottleneck'. Again, as in the previous year, the return of warmer weather favoured the Axis army, now with five extra divisions, and so the stalemate continued. By September, the Axis army had created a pocket which enclosed two Soviet armies, but by October, developments elsewhere on the Eastern Front meant that much-needed Axis troops were again withdrawn from the Leningrad operation. The people of Leningrad were now receiving much better supplies, and the city was no longer under an effective blockade.

By January 1944, the Red Army had a 2:1 troop superiority to the invaders and four times as many tanks and aircraft. The Red Army moved forward from Oranienbaum in a well-planned offensive, which pushed back the besiegers, now severely weakened through the attrition of the long campaign and the withdrawal of its best troops to other fronts. Hitler refused, however, to allow a tactical retreat. On 27 January, the Axis army defied orders and withdrew anyway. Stalin declared the blockade of Leningrad officially over. Around one million civilians had died in the siege from disease, starvation, or enemy fire. 620,000 Soviet military personnel died or were captured during the defence of the city.

Aftermath

Operation Barbarossa cost the Axis armies an unsustainable loss in men and material. The Red Army was not quickly destroyed as planned but remained ready and willing to fight on. In a long war of attrition, for which Leningrad became the ultimate symbol, the vastly superior capabilities of the USSR to replenish losses meant that Hitler could never win in the East. In May 1945, Berlin was finally occupied by the USSR, and Germany surrendered. The German-Soviet War had resulted in more deaths than in any other theatre of WWII.