The siege of Sevastopol (Oct 41 to Jul 42) was an attack by Axis forces on the base of the USSR's Black Sea Fleet during Operation Barbarossa of the Second World War (1939-45). Sevastopol (aka Sebastopol) had one of the world's strongest fortresses, but the attackers had the largest ever assembly of Axis artillery under a single army command.

While the fortress and port were besieged, a large land battle was fought in eastern Crimea. Sevastopol fell to the Axis army led by the German general Erich von Manstein (1887-1973) on 4 July 1942, consolidating the possession of resource-rich Ukraine and opening the way to the oil fields of the Caucasus.

Operation Barbarossa

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, was confident after swift Axis victories in the Low Countries and France in 1940 that he could make even greater gains in territory and resources by attacking the USSR. Hitler, as he had always promised, was determined to find Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper. Hitler was particularly interested in finding these resources in Ukraine.

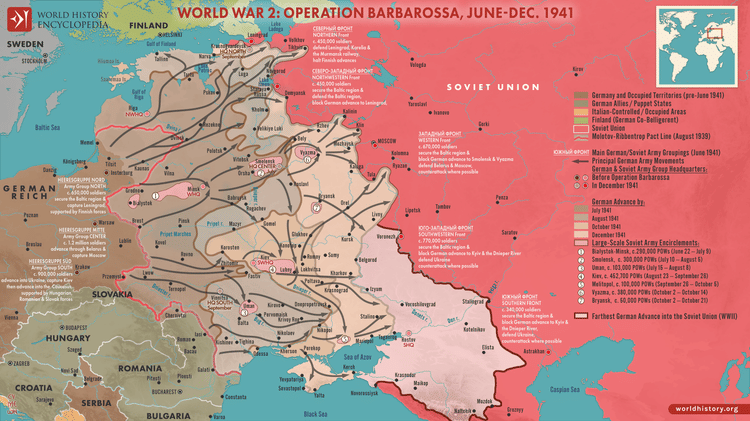

Operation Barbarossa, the code name for the attack on the USSR, was launched on 22 June 1941. The overall objective was to smash the USSR's Red Army and take control of several key cities. The invading force, made up of German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men. The overall commander was Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). The Axis force was divided into three massive army groups. Army Group South (AGS) was commanded by Gerd von Rundstedt (1875-1953). This army group consisted of between 46 and 52 infantry divisions and five panzer divisions. A significant part of the force was from the Romanian Army. AGS was tasked with striking into Ukraine.

Why Did Hitler Attack Ukraine?

The USSR had taken over the western half of Ukraine in 1939 and so now controlled the Black Sea, vital for access to the Mediterranean. The Soviet leader, Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), had subjected Ukrainians to a brutal round of arrests, deportations, and murders through 1940 and 1941, affecting hundreds of thousands of people. Here, if anywhere, the Western invaders might find a responsive people who eagerly sought to release themselves from Soviet shackles.

Hitler's territorial ambitions required resources, and Ukraine's vast reserves of wheat, coal, minerals, oil refineries, and hydroelectricity plants, if captured, would allow the invading Axis army to fight on against the USSR through 1942. In addition, Ukraine was the gateway to the oil-rich Caucasus region. Stalin had recently used Crimea as a base from which to attack the Ploiești oil fields in Romania, which were vital to Hitler's war machine. In mid-July 1941, six naval bombers of the Soviet Black Sea Fleet based at Sevastopol had hit Ploiești and destroyed 11,000 tons of oil. The loss was relatively small, but it showed the vulnerability of the oil plants. Hitler reacted to the attack by calling Crimea an "unsinkable aircraft carrier" (Forczyk, 6), and he issued a decree on 23 July that made Ukraine and Crimea priority targets.

Early Victories in Ukraine

The Blitzkrieg ('lightning war') tactics of using fast-moving armoured, air, and infantry troops to attack on a narrow front were used effectively and brought AGS such notable victories as the Battle of Uman (Jul-Aug), where Rundstedt encircled and captured over 100,000 Soviet soldiers. Next came the Battle of Kiev in 1941 (Jul-Sep), which ended in another Axis victory and where, this time, 665,000 prisoners of war were taken. A third victory came at the First Battle of Kharkov (Kharkiv) in October, where a major transport hub was taken over. As elsewhere on the Eastern Front, these huge Axis victories did not seem to appreciably dent the Red Army's capability of continuing the war. Rundstedt next had Rostov and Crimea in his sights. While Rostov was captured in December, the target further south would prove to be stubbornly resistant in one particular place: Sevastopol.

Crimea was efficiently cleared of Red Army resistance by the German Eleventh Army commanded by Lieutenant-General Erich von Manstein, a process which lasted from 26 September to 16 November 1941. Manstein was a capable commander, but he rarely visited the front lines, preferring to remain in his headquarters, a captured castle on the Black Sea coast. Key to keeping control of this region was the elimination of the USSR's Black Sea Fleet at Sevastopol, the only outpost in Crimea yet to be conquered. Manstein's army could not proceed to the Caucasus if Sevastopol remained in Soviet hands to the rear.

Fortress Sevastopol

The port of Sevastopol, located in the southwest of Crimea, possessed one of the world's strongest fortresses. The town itself had a population of around 110,000. The Black Sea Fleet based here was well-protected from a naval attack by high cliffs while a land-based attack also faced difficulties of geography and a triple arc of major defensive lines placed several miles out from the port. These lines included over 3,000 well-hidden earth and timber bunkers, anti-tank ditches, trenches, and 140,000 mines, although some parts remained unfinished by the time the Axis army arrived. The fortress boasted 12 naval gun batteries, which provided a total of 42 powerful guns. These guns, protected by bunkers, could strike at any naval attack but also cover the coast itself.

The defence of Sevastopol was made the responsibility of Vice Admiral Filipp Sergeyevich Oktyabrsky (1899-1969), commander of the Black Sea Fleet. There were eventually around 52,000 troops defending Sevastopol (Forczyk, 11). These men, under the command of Major-General Ivan Yefimovich Petrov (1896-1958), mostly protected the land approach to the port. Many of the troops had escaped the Axis victory at the siege of Odessa to the west a few weeks earlier, while several more battalions came from the crews of the naval ships anchored in the port. The naval infantry was equipped with rifles, machine guns, and mortars. A third part of the defence force came from reinforcements sent from Yalta and the Caucasus in November. Oktyabrsky could also rely on regular supplies coming in by ship from Novorossiysk (a Soviet port on the eastern shores of the Black Sea), although these had to move at night to avoid attacks from Axis aircraft.

The Soviet Black Sea Fleet consisted of 47 submarines, 21 destroyers, 6 cruisers, and one rather obsolete battleship. By the autumn of 1941, the ships were protected by a significantly reduced air force of around 60 fighter planes. It was felt prudent to move most of the fleet to safer waters to the east. At the time of the siege of Sevastopol, the following ships remained to offer their guns in the coming battle: one heavy cruiser, two light cruisers, and seven destroyers. Germany, meanwhile, had sent no ships to the Black Sea and relied on a handful of small vessels from its Romanian ally. On paper, the numbers favoured the Soviets, but because of their antiquated equipment and the constant threat from Axis air attacks, "at no time did the Soviet Black Sea fleet dominate" (Dear, 105). One area in which the fleet did perform well was as a support for the Red Army's coastal operations and harassing Axis supply ships.

Manstein Attacks

To attack Sevastopol, Manstein had a relatively small army consisting of seven divisions with additional Romanian divisions (about one quarter of the Axis force). The two Romanian mountain divisions were elite troops, but the rest were poorly trained and equipped infantry divisions. He lacked both tanks and heavy artillery in sufficient numbers. In addition, much of Manstein's air support was withdrawn to support campaigns elsewhere, such as at the Battle of Moscow. None of his units were at full strength either after enduring a bruising campaign since the summer. Still, Manstein launched Operation Störfang ('Sturgeon Haul') with the first artillery bombardment of Sevastopol on 30 October. Through November, a series of relatively light infantry and armoured attacks were launched in the hope of a quick victory. The outer defences of Sevastopol held.

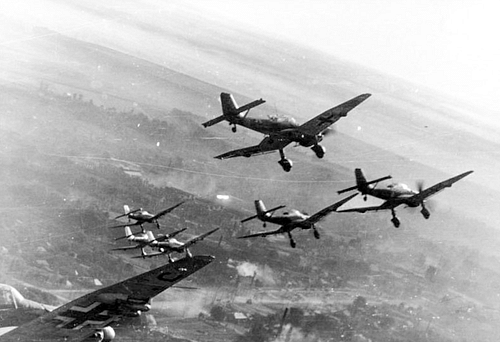

Poor weather then caused a delay, with Manstein not able to start his main attack until 17 December. The Axis infantry, equipped with high explosives, flame-throwers, and grenades, steadily beat their way through the three defensive lines protecting Sevastopol over the next ten days. The advance through the difficult terrain was helped by the return of Luftwaffe (German Air Force) planes: 34 Junkers Ju 87 'Stuka' dive bombers and 20 medium bombers. The Axis army still faced the fortress proper of Sevastopol.

While Sevastopol was under attack, the rest of Crimea, particularly the southern coast, remained vulnerable to a Soviet counterattack. The Soviets were also able to ship in another 11,000 troops to Sevastopol through December and to ship out a number of wounded. Manstein's troops began to dig their own trenches as it became clear Sevastopol would only fall after a lengthy siege. The Axis positions now came under fire from the Soviet battleship Parizhskaya Kommuna, although this reappearance was short-lived since it soon wore out its gun barrels.

Kerch: The Soviet Counterattack

With the invaders concentrating on Sevastopol, from 26 December, the Red Army attacked Kerch at the eastern end of Crimea using hundreds of small boats. On 28 December, another Soviet army landed at Feodosiya to the west of Kerch. In fact, there had been 25 separate landings, but only four stuck to create a lasting beachhead; but it was enough. Manstein was obliged to withdraw two divisions from his attack on Sevastopol to prevent the enemy force of 28,000 men sweeping across Crimea. This action greatly relieved the pressure on Sevastopol and delayed a large offensive Manstein had planned.

Worse was to come for Manstein when, in January 1942, the winter weather froze the narrow Kerch Strait and allowed yet more Red Army divisions to pour into Crimea by truck. As in the other sections of Operation Barbarossa, the German generals were being asked to take objectives with insufficient troop numbers to accomplish the task.

The USSR high command was able to use Kerch as a springboard and create what it called the Crimea Front. The Red Army, actually now three army groups, was here commanded by Major-General Dmitry Timofeyevich Kozlov (1896-1967). The winter conditions did not deter the Soviets from making several offensives, but all were ineffective and resulted in high casualties.

Manstein launched his own fightback in May, Operation Trappenjagd ('Bustard Hunt'), using one panzer division, five German, and two and a half Romanian divisions. Kozlov, having bulked up his army through the continuous arrival of men and material across the Kerch Strait, was now in command of 21 divisions. The Axis tanks numbered around 180 while the Red army fielded 350. On 8 May, Manstein audaciously sent a force by boat to land and cut in half the Soviet positions. Fighting over the next ten days ended in an Axis victory, and the peninsula was regained. According to Manstein, his army captured "some 170,000 prisoners, 1,133 guns and 258 tanks" (Boatner, 293). Kozlov was dismissed for this disaster, but, not for the first time, Stalin's express orders that there be no retreat had only resulted in greater losses than were necessary. Now, at last, Manstein could reconcentrate on taking Sevastopol.

The Fortress Battle

Manstein continued to besiege the port from the land side. Hitler was intent on capturing the fortress for purposes of prestige and propaganda – by a self-imposed target date of 23 June – and so sent to Manstein a number of huge artillery guns to blast the fortress into submission. In all, Manstein fielded almost 900 guns, "the largest collection of artillery pieces under a single command by the German Army in World War II" (Forczyk, 27). Amongst this impressive assortment of guns were two with a massive calibre of 600 mm (23 inches). These twins of the Karl mortar type were nicknamed 'Thor' and 'Odin' after the gods of Norse mythology, and they could fire 2.4-ton concrete-piercing shells capable of punching through any gun emplacement the enemy could build. The biggest gun of all, in fact the largest artillery piece ever built, was the railway gun 'Dora', which had a calibre of 800 mm (31 inches) and could fire a shell a distance of 30 miles (47 km). 'Dora' had been specifically designed for siege warfare. Impressive though these monster guns were, they were not easy to set up, took time to load using a crane, and had a poor level of accuracy. Manstein did not have very many shells for these behemoths either, only 122 for 'Thor' and 'Odin' and 48 for 'Dora'. The smaller calibre guns with their tens of thousands of stockpiled shells, in the end, proved much more valuable to the attackers. By the end of May 1942, the Axis artillery was ready to fire at Sevastopol. The defence, by now consisting of 106,000 army troops and 80,000 naval personnel, thanks to constant resupply from the Black Sea Fleet, braced itself for the onslaught.

A five-day artillery barrage and air attack on Sevastopol began on 2 June. There was supporting fire from a newly arrived Italian light naval squadron on the Black Sea. On 7 June, four Axis divisions attacked the port from the north. On 11 June, another three divisions attacked from the southeast. Both land attacks, although wearing down the enemy, ultimately failed, and even the artillery barrage was a disappointment for the attackers, the really big guns being somewhat wasted by attacking too many different targets. Chunks of the Sevastopol fortification network were blasted out of place, but most of the defensive artillery was well-placed and well-protected in natural caves. The defenders were still capable of strong resistance as the attackers got bogged down working through the hilly terrain and masses of wires and mines. Axis aircraft had initially done well against their Soviet counterparts, but they could not knock out the airfields, and so the Red Air Force remained operational throughout June and able to replace losses from the Caucasus.

Both sides were steadily wearing each other down through the middle of June, with heavy fighting around certain strategic points like Fort Stalin, Fort Maxim Gorky, Fort Kuppe, and Chapel Hill. Some defensive positions were weakening, but the minefields required time to clear. Remote-controlled demolition vehicles were sent in to clear some areas, but these were not as effective as hoped.

Manstein was obliged to try something different, and so, just as he had done on the Kerch front, he turned to the sea. In the early hours of 29 June, an amphibious assault consisting of 130 small boats, each carrying six men, headed across the Severnaya Bay to attack the port from the sea. Protected by a smoke screen and supported by an artillery barrage, the attackers achieved total surprise and established a beachhead. Reinforcements soon came with heavier weapons, and the last line of Soviet defence was breached. With the situation now hopeless, the Soviet military leaders, including Petrov, were evacuated by submarine on 30 June. Oktyabrsky was flown out on 1 July. Stalin had ordered the commanders' evacuations, but the practical result was that those left behind lost heart and the resistance weakened significantly. Sevastopol and its environs were finally captured on 4 July 1942, most of the town having been reduced to rubble. Around 95,000 Soviet prisoners were taken. Manstein was promoted to field marshal.

Aftermath

Initially, as Axis soldiers have recounted, the invaders in Ukraine were often regarded as liberators, and the local people gave the new arrivals such traditional gifts of hospitality as bread and salt. This warm welcome, although not universal, soon cooled dramatically. Ukraine, including Sevastopol, was subjected to Nazi rule, which included atrocities against Soviet commissars (political officers) and Jewish people, amongst others. Einsatzgruppen mobile killing squads shot people without trial. The harsh treatment of the population in general, as Hitler sought merely to exploit for all they were worth the region and its people (whom he regarded as racially inferior), meant that Ukrainian resistance soon grew to trouble the new occupiers, and so, in turn, the episodes of Nazi brutality increased. 7 million Ukrainians died during the conflict as a whole. Millions of Ukrainians were displaced for use as forced labour. According to Albert Speer (1905-1981), Hitler's armaments minister, 500,000 young Ukrainian women were moved to Germany to work as domestic servants for Nazi Party members.

On the wider front, the Red Army fightback had begun with the Battle of Moscow and resistance at the siege of Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) through the winter of 1941/2. AGS's charge eastwards was halted by the accumulation of losses in men and material, the poor road systems hampering logistics, and the continued resistance of the Red Army. The German-Soviet War had already entered a new phase, one which would last for three more years and result in more deaths than in any other theatre of WWII. In the winter months of 1943/4, Ukraine was retaken by the Red Army. In May 1944, Sevastopol was recaptured from the Axis occupiers. In May 1945, Berlin was finally occupied by the USSR, and Germany surrendered. In the titanic struggle between dictators, Stalin had beaten Hitler.