The Battle of Moscow (Oct 41 to Jan 42) was Germany's first major land defeat in the Second World War (1939-45). Although Axis panzer divisions reached within 20 miles (32 km) of the Soviet capital, the USSR's Red Army, led by Marshal Georgi Zhukov (1896-1974), launched a series of counterattacks in December 1941 that pushed the invaders back westwards.

Moscow itself saw no fighting, and the push for the capital was one advance too many for the Axis armies as Operation Barbarossa ended in a whimper. Despite a string of huge victories earlier in the campaign, the invaders had lost too many men and too much material to continue the operation effectively. Poor roads and winter weather meant fresh Axis troops and supplies could not reach the front in sufficient quantities. The Red Army fought its best battle of the war so far, and the Soviet Union's victory meant Moscow was saved.

Operation Barbarossa

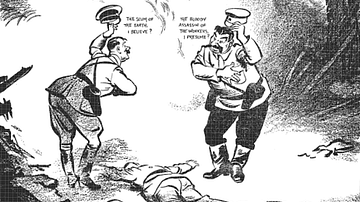

Adolf Hitler (1889-1945), the leader of Nazi Germany, was confident after swift Axis victories in the Low Countries and France in 1940 that he could make even greater gains in territory and resources by attacking the USSR. Hitler, as he had always promised, was determined to find Lebensraum ('living space') for the German people, that is, new lands in the east where they could find resources and prosper. Hitler was convinced that by destroying the Red Army and taking prestige cities like Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) and Moscow, the USSR would collapse. Accordingly, Operation Barbarossa, the code name for the attack on the USSR, was launched on 22 June 1941.

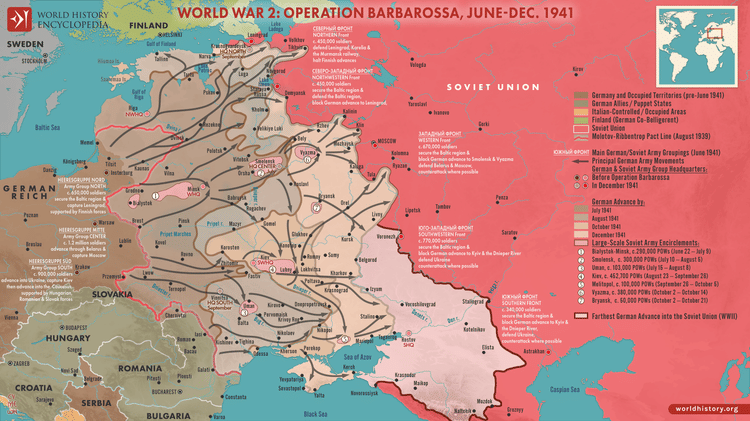

The invading force, made up of German, Slovakian, Italian, Romanian, and Finnish forces, amongst others, consisted of 3.6 million men. The overall commander was Field Marshal Walter von Brauchitsch (1881-1948). The Axis force was divided into three massive army groups. Army Group North (AGN) was tasked with taking Leningrad. Army Group South (AGS) moved to conquer Ukraine. Army Group Centre (AGC), commanded by Fedor von Bock (1880-1945), punched through the Soviet defensive lines in the summer, using Blitzkrieg ('Lightning war') tactics, which combined air support with fast-moving armoured and infantry divisions advancing on narrow fronts. Great victories were achieved at the Battle of Białystok-Minsk (Jun-Jul) and the Battle of Smolensk in 1941 (Jul-Sep).

Target Moscow

Initially, Moscow was not one of Hitler's primary targets since he wanted first to destroy the Red Army in the field. However, after these early victories, where over 650,000 enemy soldiers were captured, he changed his mind and sent Bock to attack Moscow. There had been a delay of several weeks over this decision, a delay Hitler's generals regretted since it gave the enemy time to build better defences around the capital. Hitler had also diverted AGC's two armoured groups to help AGN in the Siege of Leningrad and AGS in the Battle of Kiev in 1941. This was deemed necessary to prevent counterattacks against AGC's flanks as its infantry divisions penetrated deeper into the USSR. Hitler's new directive of 6 September ordered Bock to attack the Red Army front protecting Moscow, actually three fronts: the Western, Reserve, and Bryansk fronts.

Hitler had once described Moscow as the capital of the "Judaeo-Bolshevist world conspiracy" against Germany (Rees, 14). The city certainly had a prestige value, but it was also the most important transport and communication hub of the USSR. Taking Moscow, then, would surely destroy one of the great enemies of Nazism. On 2 October, the Axis attack on the Moscow fronts, code-named Operation Typhoon, was launched. The objective was a gamble: to take Moscow before the Russian winter hit and the Red Army could draw on massive reserves from the east.

The Red Army's positions at the towns of Bryansk and Vyazma were the last obstacles on the long road to Moscow. Once again, poor leadership, antiquated weaponry, and the wastage of tanks by using them only in small groups, all meant the resistance to the invaders was insufficient to avoid defeat at Vyazma on 10 October and at Bryansk on 13 October. Another 650,000 Soviet prisoners and 1,200 tanks were taken in the two combined battles as the Axis panzers utilised their now-familiar pincer and encirclement manoeuvres. Next, on 14 October, Kalinin was captured. On 18 October, Mozhaysk was taken. Both of these cities were key to Moscow's defensive lines, but, in the giant encirclements so far in Operation Typhoon, at least 200,000 Red Army soldiers managed to escape to fight another day. The Axis army was closing in on Moscow while the Axis air force began to bomb the capital, but only in small raids.

Problems of Logistics

The Axis victories had come at a cumulative cost in men and material and now this began to tell. The retreating Red Army was very particular in destroying anything that could be of use to the advancing enemy. Crucially, Stalin had shifted most manufacturing to the safety of Central and Eastern Russia, and this plan now paid dividends as losses in the field could be replaced and supplies given to troops under sustained attack. The Axis armies, on the other hand, faced ever-increasing difficulties in getting their supplies, given the great distances involved as they pushed deeper into Russia. As General Hasso von Manteuffel (1897-1978) noted: "The spaces seemed endless, the horizon nebulous. We were depressed by the monotony of the landscape and the immensity of the stretches of forest, marsh and plain" (Stone, 146).

Roads were poor or non-existent, bridges were few and far between, and villages had nothing much to offer by way of supplies. German logistics were also severely challenged by Stalin's orders that partisans sabotage Axis supplies wherever possible. On top of all that, late autumn conditions in 1941 made what roads there were muddy, and so logistics became extremely difficult. As winter approached, more problems arrived. Operation Barbarossa was not meant to last this long, and now the lack of strength in depth of the invading army, after sustaining regular losses for five months, was beginning to tell. The Axis reserves were wholly inadequate for a long campaign. Many of the Axis troops lacked essential equipment and even the proper clothing for winter conditions.

Moscow's Defences

In mid-October, as Typhoon got underway, many Muscovites were convinced their city would fall just like Minsk, Smolensk, and Kiev had. The authorities had a similarly pessimistic view. Even the embalmed body of Vladimir Lenin (1870-1924), founder of Soviet Russia, was removed to a place of safety. Many people tried to leave by train or boat, but the options were few after more than one million people had previously been evacuated. There were rumours that the Axis troops had already entered the city. Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), the Soviet leader, reacted to the initial defeats and brutal nature of the campaign by declaring this a 'Patriotic War' where everyone must offer nothing less to the enemy than a 'relentless struggle'.

Significantly, Stalin himself remained in Moscow and was seen in Red Square overseeing a parade. Stalin got tough on the population. A curfew was imposed from 20 October. Armed units of the secret police, the NKVD, kept public order and reduced looting. Punishments would be imposed on those who did not fight as required. Stalin ordered that deserters should be summarily shot. The Red Army and the people of Moscow were, though, determined that the invasion of their country should stop here and the fightback begin. The Soviet leader called for the entire city to become a fortress, and this is what happened. Streets were barricaded and littered with anti-tank obstacles. 90,000 soldiers defended the city itself. Labour and militia divisions totalling 65,000 men were formed from the civilian population. 600,000 civilians, armed with spades and picks, dug a huge arc of anti-tank ditches to protect Moscow.

A Moscow resident, Dr Grigori Tokaty, remembers the collective action of the capital's civilians:

Literally hundreds of thousands of women and people with children, old men, were digging defence lines at the very same time outside of Moscow. Hundreds of thousands of ordinary people, without being mobilised, doing everything possible for their town, for their history.

(Holmes, 185)

The defence of Moscow was orchestrated by Marshal Zhukov, the Soviet Union's best commander. Zhukov took on the job in mid-October and insisted he needed more men, tanks, artillery, and rockets to mount an effective defence. Stalin promised these, and, in return, Zhukov declared "we will hold Moscow" (Rees, 71). Three weeks of rain helped the Red Army organise itself as the attackers could not proceed to Moscow. In all, nine reserve armies would be stationed behind the River Volga, around 900,000 men in all.

The Axis air offensive against Moscow had been running since August, but it was a piecemeal operation due to aircraft being needed in a great many other places. The Luftwaffe's lack of a purpose-built heavy bomber, as it had been in the Battle of Britain, was another serious weakness. The approaches to Moscow were well-protected by "800 medium anti-aircraft guns, over 600 large searchlights and nearly 600 fighters" (Stahel, 305). The city itself had hundreds more anti-aircraft guns and over 100 barrage balloons. In total, "the raids killed only 736 Muscovites and wounded 3,513 more" (Kirchubel, 57). The Red Air Force, meanwhile, began to attack the Axis airfields and so gained supremacy in the air. If the capital was to be taken, it would have to be done by infantry and armoured divisions on the ground.

Typhoon Stalls

When the rains stopped and the terrain began to harden on 15 November, Operation Typhoon resumed in earnest. The two main panzer group commanders were Georg-Hans Reinhardt (1887-1963) and General Heinz Guderian (1888-1954). Both panzer commanders advanced on Moscow and attempted an enveloping manoeuvre to the southeast and north. At the northern end of the Axis front, the Third Panzer Group reached the Moscow-Volga canal on 27 November, just 37 miles (60 km) north of Moscow. The Second Panzer Army at the southern end of the front was at the river Oka 62 miles (100 km) southeast of Moscow. By 4 December, in the middle of the front, Fourth Panzer Group had moved to within 20 miles (32 km) of Moscow. The advancing soldiers imagined they could see the spires of the Kremlin on the far horizon, but the Axis spearhead was already blunt. The panzer divisions were rather worn out after their overuse in the earlier campaigns against Leningrad and Kiev (Kyiv), and they were without reserves. As the commander Hasso von Manteuffel (1897-1978) noted, "the [earlier] dispersion was the main failure of the campaign and when Hitler ordered to attack Moscow at the end of October we had not sufficient forces to attack" (Holmes, 185). By the end of November, Quartermaster General Edward Wagner bluntly reported: "We are at the end of our personnel and matériel strength" (Dear, 89).

The Axis artillery did fire at Moscow, but it was merely a symbolic gesture. The advance up to 4 December proved to be the Axis high point. The tide of the Eastern Front was about to be reversed. Developments in the war elsewhere did no favours for Hitler either. With Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour, the US naval base in the Pacific, on 7 December, suddenly WWII expanded. Most importantly for the battle for Moscow, Japan would now be concentrating on the Pacific and so would no longer be a direct threat to the USSR. Stalin could, therefore, move troops from Eastern Russia to the Moscow Front. Using nine train lines, one new division arrived in Moscow every two days and, in total, 70 divisions were added to the city's defence. On the other side, Bock had just one train line for resupply purposes. By early December, the Red Army had around 4 million men to defend the capital, while the Axis army numbered around 2.7 million (Kirchubel, 78).

Zhukov's Fightback

Zhukov marshalled his now impressive resources for a series of counterattacks, which began on 6 December 1941. Zhukov deployed 100 divisions of well-equipped men along a 200-mile (320-km) long front. The Axis forces had been ready to attack Moscow and so were unprepared in terms of defence. "Having not bothered to build a solid front while they were on the move, the German armies could neither dig in the frozen ground nor close the gaps between them" (Dear, 343). Those troops who could retreat soon blocked the narrow roads leading westwards. General Franz Halder (1884-1972), Hitler's chief of the Army General Staff, described the situation as "the greatest crisis in two world wars" (ibid).

By mid-December, the Red Army's counterattack had turned into a full-scale counteroffensive. Zhukov was determined to push back the enemy to where Operation Typhoon had started. Everything seemed to be going against the invaders. Due to illness, Bock had to be replaced by Günther von Kluge (1882-1944) as commander of AGC on 19 December 1941. Zhukov kept on pushing, and by 7 January 1942, the Axis forces were back to where they had started the previous November.

The Soviets fought fiercely, and they were now using the new T34 tank and other models in larger and much more effective battle groups. The 26-ton T34 tanks were superior to any the Axis armies fielded and could resist most anti-tank guns. In summary, the T34 "had a simple diesel engine (500 hp), good armour, excellent firepower, and superb mobility in snow and mud" (Boatner, 702). Another very effective Soviet weapon, a highly secret one, was the BM-13 Katyusha rocket launcher. Mounted on a truck, this weapon could rapidly fire 16 132-mm rockets. Perhaps surprisingly, the Red Army cavalry – which made up 15 divisions – was another effective weapon of the counteroffensive.

Zhukov's army was actually not quite ready for a grand push on the enemy since its logistics for mobile warfare were still inadequate. The Axis army had much greater problems, though. Most of the horses on which the Axis artillery depended to move their equipment died of heart failure in the snow. The freezing temperatures were causing serious problems with equipment, too, as here remembered by artillery Lieutenant Heinrich Schmidt-Schmiedebach:

At first it was not so bad, perhaps fifteen or twenty degrees under zero and there was no danger for our weapons. But suddenly at a certain point the rifles didn't shoot any more. This was the turning point in the winter war, I think, and it was the greatest point for the soldiers. The lubricating oil we had was not suitable for this sub-arctic winter, but the Russians had the real lubricating oil for their weapons.

(Holmes, 189)

Most Axis troops had to sleep in holes in the snow. Walter Schaefer-Kehnert, who belonged to a panzer unit on the very front line, remarked, "We had huge losses from frozen toes and fingers during the night" (Rees, 78). These were the lucky ones, others simply froze to death. Some units did have winter clothing but not enough, and stockpiled supplies were blocked in Poland. Back in Germany, Hitler's propaganda minister, Joseph Goebbels (1897-1945), was obliged to launch a humiliating nationwide appeal for warm coats to be sent to the soldiers on the Russian front. In any case, Hitler sent orders that there be no retreat, an order his generals disagreed with as it severely limited their possibilities of manoeuvre and more or less guaranteed heavy losses to the enemy.

The Red Army ferociously fought forward and "repulsed all three German panzer armies from Moscow, and ...[threw] five out of six armies in Army Group Centre into disarray" (Forczyk, 88). The German generals did manage to get their retreat together eventually and prevent a total collapse of the Eastern Front, but they had lost at least 110,000 men by December alone (Forczyk, 89). The Red Army's eventual stall was due to Stalin ordering the bulk of his forces to attack the flanks of the retreating army groups, a strategy Zhukov did not have adequate resources to carry out effectively after suffering around 350,000 casualties during the battle as a whole. Nevertheless, the Soviet attacks through December 1941 to March 1942 pushed the Axis forces some 175 miles (280 km) from Moscow. The capital was now secure.

As the Red Army advanced for the first time after a long series of retreats, the horrors of what the occupiers had perpetrated became clear. Homes had been razed to the ground, property of all kinds stolen, and civilians of all ages murdered. Many Axis troops taken prisoner suffered mutilation and execution, as had been the reverse case earlier in the campaign. The Eastern Front had become a tragedy of hatred.

Aftermath

The battle for Moscow was Hitler's first strategic defeat in the East. He, of course, blamed his generals, sacked Barbarossa's overall commander Brauchitsch, and took personal command of the German Army. Stalin had won a great victory and shown that Hitler's armies were not invincible, but it was clear they remained a threat and would very likely continue their campaign when warmer weather returned. The German-Soviet war went on for three more years and accounted for at least 25 million military and civilian deaths, perhaps half of the overall WWII death toll. When the Red Army advanced on Berlin, Hitler committed suicide in April 1945, and Germany surrendered.