The Battle of Edington, fought in May 878 in southwest England, saw Alfred the Great, King of Wessex (r. 871-899), win a decisive victory over the Viking leader Guthrum (d. 890). Two weeks later, under the terms of the Treaty of Wedmore, Guthrum surrendered, agreeing to both convert to Christianity and leave Wessex.

In the months leading up to the battle, the Vikings had overrun much of England, and with Guthrum's invasion of Wessex in January 878, the last Anglo-Saxon kingdom stood on the brink of collapse. After being forced into hiding in the Somerset marshes, Alfred eventually regathered his army and defeated the invaders. His triumph compelled Guthrum to retreat to East Anglia, where he ruled as king.

In the years that followed, the two kings worked to establish a more peaceful coexistence between the Norse settlers and the Anglo-Saxons. However, Alfred's successors eventually embarked upon the reconquest of the lost Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, and Edington would, in time, be marked as the first of many great victories in their quest to unify England under a single ruler.

The Vikings' Arrival

The Viking raids in Britain started in 788, when three ships of Norse pirates landed at Portland, Dorset, where they killed a local reeve (royal official). However, the raid that truly horrified the Anglo-Saxons came five years later when a group of Vikings attacked the monastery of Lindisfarne near the Anglo-Scottish border, which housed the relics of Saint Cuthbert, one of England's most revered saints. The famous scholar Alcuin (d. 804) lamented, "Behold, the church of St Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than all in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples" (Whitelock, 899).

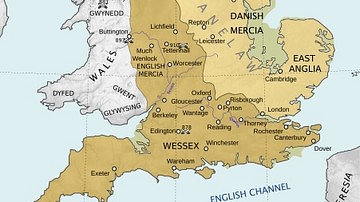

Emboldened by their early success, by the mid-9th century, the Vikings were targeting the wealthy towns of Canterbury and London and defeating kings in battle. Alfred was born into this turbulent and unstable world in 849. England as we know it today did not yet exist and was divided into four kingdoms: East Anglia, Mercia (the Midlands), Northumbria (northern England), and the southern kingdom of Wessex, which was ruled by Alfred's father, King Aethelwulf (r. 839-858).

By 865, the Viking threat escalated as Ivar the Boneless, the Viking ruler of Dublin (r. 857-873), assembled a coalition of fleets – known to contemporaries as the 'Great Army' – from Norse bases in Francia, Frisia, Scandinavia, and the Hebrides. Backed by perhaps as many as 5,000 warriors, Ivar and his allies achieved swift success, conquering York, the capital of Northumbria, in 866. Three years later, in 869, they turned south to East Anglia, defeating its ruler, King Edmund (r. 855-869). After refusing to surrender to pagans, Edmund was rewarded with a martyr's death – tied to a tree, he was fired at with spears and beheaded.

Wessex & the Vikings

After the conquest in East Anglia, Ivar went to fight the Strathclyde Britons (modern-day southwest Scotland), leaving his brother Halfdan in command of the remaining army. In the winter of 870, they sailed up the Thames, arriving at Reading on the northern border of Wessex. The following year, 871, saw nine hard-fought battles between the Great Army and Wessex. Led by Aethelwulf's son, King Aethelred (r. 865-871), the West Saxons won unexpected victories at Englefield and Ashdown in Berkshire but suffered losses at Basing and Merton in Hampshire.

The spring of 871 would shift the stalemate in favour of the Vikings; they were reinforced by a fleet led by Guthrum, a seasoned sea king and a relative of the Danish royal family. His followers whispered that the Danish throne should have been his had he not been robbed of it as a young man. Guthrum, nevertheless, settled for the lucrative life of a raider and now sensed limitless opportunities for plunder and conquest amongst the unravelling Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

Wessex's precarious position was worsened by the death of King Aethelred, who likely died from battle wounds. He was succeeded by his younger brother, Alfred. Aged 22, Alfred was sickly and bookish, yet he had proven himself a brave warrior at Ashdown. However, unable to dislodge the Vikings from Wessex, by the end of the year, he decided to pay them to leave his kingdom. The sum paid was likely extortionate, but it nevertheless would give Wessex peace – at least for a few years.

Returning north, the Great Army next targeted the Midland realm of Mercia. The Mercian ruler, King Burgred (r. 852-874), attempted to keep the Vikings at bay, paying them in exchange for peace, but when the Great Army attacked in 874, he was forced to abdicate and flee across the English Channel. His replacement, Ceolwulf II (r. 874-879), was compelled to surrender half of his kingdom, allowing the Vikings to settle in the East Midlands and use his towns as military bases. Thus, by 874, Wessex stood as the last truly independent Anglo-Saxon kingdom.

The Ambush at Chippenham

Guthrum took control of the Great Army in 875, with Halfdan leaving to fight the Scots. The following year, he led a second invasion of Wessex, but by 877, the conflict reached a deadlock, and peace was secured with oaths from Alfred and Guthrum, who retreated to Gloucester in southwest Mercia. As 877 came to an end, Alfred arrived at Chippenham, in northern Wiltshire, where he would spend Christmas. Accompanied by his friends and family, he could briefly set aside the heavy burden of kingship and reflect on his reign.

The Christmas festivities lasted 12 days, from 25 December to 6 January. On Twelfth Night, the great hall of Chippenham was noisy and jubilant, with feasting and celebration. The veterans of the 871 campaign raised their cups to the death of Halfdan, killed in Ireland a few months before, while poets sang of Alfred's bravery at Ashdown. But suddenly, the hall went quiet. Distant shouts from the town's gates turned to screams. Guthrum, ignoring his vows of peace, had led his army south from Gloucester under the cover of night. While the town's defenders were distracted with the festivities, he stormed Chippenham's walls, slaughtering any who stood in his way. But somehow, amidst the chaos and violence, Alfred, his family and a few household warriors escaped, fleeing westward into the night.

Yet, not every West Saxon saw this as a disaster. The man responsible for Chippenham, Ealdorman Wulfhere of Wiltshire, allied himself to Guthrum. Believing he was choosing the winning side, Wulfhere sensed new opportunities in partnering with the Vikings. He perhaps even aspired to wear the West Saxon crown on Guthrum's behalf, providing legitimacy to Viking rule. What remained of the West Saxon nobility was now scattered and leaderless. Some had died at Chippenham, others fled across the Channel, and many retreated to their estates, hoping Guthrum would leave them alone.

However, Guthrum knew that to break Wessex, he had to capture and kill its king. Thus, in fear for his life – without an army or time to raise one – Alfred fled to the Somerset marshes, where, according to his contemporary biographer, Bishop Asser, he lived "in great tribulation an unquiet life among the woodlands and swamps" (Cook, 18). Nevertheless, he was hidden or at least shielded from the invaders by the treacherous marshy terrain. Indeed, in the TV series The Last Kingdom (2015-2022), at this very moment, Guthrum (played by Thomas W. Gabrielsson) is urged by one of his commanders to chase after Alfred. To which he responds, "Only a fool would lead an army into the swamp land."

Myths & Marshes

Alfred's first days in the shadowy Somerset marshes, seeking refuge, hunting, and fishing to survive, became the setting of many myths and legends. The most famous is Alfred and the Cakes, in which, travelling alone and disguised as an ordinary man, Alfred takes shelter in the cottage of a swineherd. The man's wife, preoccupied with cleaning, asks her guest to watch over some cakes she is baking. Lost in thought, dwelling on his failures, Alfred loses track of time, and the cakes burn. Smelling the smoke from across the room, the swineherd's wife scolds Alfred, telling him, "Look here, man, You hesitate to turn the loaves which you see to be burning. Yet you're quite happy to eat them when they come warm from the oven" (Keynes and Lapidge, 198). Rather than revealing his true identity, Alfred humbly apologises and helps with the cakes.

In another story, Alfred and his companions are fishing when a hungry pilgrim approaches them, asking for food. Despite his meagre rations, Alfred orders his servants to prepare a meal for the pilgrim, who mysteriously vanishes. That night, Saint Cuthbert appears to Alfred in a dream. Cuthbert reveals that he was the pilgrim in disguise, and, as a reward for the king's generosity, he would help the West Saxons defeat the Vikings. While these stories are generally regarded as myths rather than fact, they nevertheless reflect how Alfred was remembered – a humble and generous ruler who treated even the lowest of his subjects with respect.

Myths aside, Alfred mostly spent his time plotting a return to power. He could not do this alone, however, and shortly after his flight to the marshes, he was joined by Ealdorman Aethelnoth of Somerset, who brought soldiers, supplies, and local intelligence to Alfred's cause. By Easter of 878, they had built a fortress, Athelney, deep in the marshes, to serve as their base of operations to begin the fight back for Wessex. Without the numbers to take on Guthrum directly but with extensive knowledge of the local terrain, Alfred waged a guerrilla war against the Vikings. Emerging daily from the marshes, he and his warbands raided the estates of those who had sided with Guthrum, ambushed the enemy's patrols and disrupted Viking supply lines. With each attack, Alfred pronounced that he was still king and was willing to fight for his crown.

Meanwhile, further west, a second Viking army landed on the northern coast of Devon, seeking to trap Alfred between themselves to the west and Guthrum's army to the east. But their plan was thwarted by Ealdorman of Devon, Odda, who remained loyal to Alfred, and near Countisbury in northern Devon, he annihilated the invaders. This victory and the relentless guerrilla campaign brought new recruits to Alfred's side, and by the beginning of May, he rode out from the marshes, sending messengers to Hampshire, Somerset, and Wiltshire, demanding every man capable of fighting to take up arms. The rallying point was Egbert's Stone – a now-lost monument to Alfred's grandfather on the Somerset-Wiltshire border. Many answered the call to arms, and as told by Asser, "when they saw the king restored alive, as it were, after such great tribulation, they were filled, as was meet, with immeasurable joy" (Cook, 19).

The Battle

With the armies of Hampshire, Somerset, and Wiltshire – much of which had abandoned their ealdorman, Wulfhere – Alfred was ready to confront Guthrum, who left Chippenham and marched to face the reformed army of Wessex. Both men knew this confrontation was not merely a battle but a verdict on who would hold power south of the Thames.

It is unknown how large Alfred's army was, but it was likely in the low thousands, and for Guthrum to abandon Chippenham's walls and risk open battle, he probably had similar numbers. Alfred's troops camped at Egbert's Stone before marching east at dawn, crossing into Wiltshire, where they camped at Iglea – an unidentified site near Warminster. The next morning, they continued their march and, after several hours, spotted Guthrum's army near the royal estate of Edington in southwest Wiltshire.

Contemporary sources offer few details about the battle itself, but we can imagine Alfred praying for divine favour before battle and rallying his troops with words of duty and faith, reminding them that this was a battle for their kingdom's survival. In The Last Kingdom, before this great confrontation against the Vikings, Alfred (played by David Dawson) addresses his troops with a more brutal message: "We shall make the ground red with their blood. We shall strip them of what they have plundered. We shall make them cry out for mercy, and there shall be none. No mercy!"

With pre-battle rituals complete, both sides assembled their ranks, and Alfred ordered his men to form a shield wall – a standard feature of Anglo-Saxon warfare, a line of locked shields which no enemy could easily break. Seeing this, Guthrum's army advanced. As the two sides got closer, their battle cries filled the air, followed by an exchange of missiles, with stones, javelins, and arrows being fired by both armies. Then, the two sides clashed, with axes thudding into wood and iron and the sound of clanging steel as swordbearers struck at one another. The Viking attacks were relentless, but the men of Wessex remained firm and disciplined, meeting each assault with the thrusting of their spears. Asser tells us Alfred led his troops into battle, fighting "fiercely" and "perseveringly" (Cook, 19). As the day wore on, Viking attacks eventually slowed and then stopped altogether. Late in the day, Guthrum, witnessing his men falling in droves, ordered a retreat. Yet, for the West Saxons, the battle was far from over. They pursued their fleeing foes with merciless enthusiasm, striking down stragglers and the wounded from behind. The defeated army's destination, Chippenham, 15 miles (24 km) from Edington, made their desperate retreat continue deep into the night. Upon reaching the town, the Vikings survivors barricaded themselves behind its walls, but Alfred arrived shortly after, surrounding Chippenham and putting it under siege.

Guthrum was left with a much-diminished army, insufficient food supplies, and no way out. He lasted two weeks before starvation drove him to surrender. He offered promises of peace to Alfred and begged the king to allow him to leave Wessex. However, Alfred had come to distrust Guthrum due to his past betrayals. In Alfred's view, Guthrum's deceitfulness derived directly from his pagan faith. Thus, as a condition of peace, Alfred demanded that Guthrum and his chief followers convert to Christianity. Only as a fellow Christian prince, he reasoned, could the Viking leader be trusted to keep the peace and be a partner in building a more prosperous future for both sides. Left with no alternative, Guthrum yielded to Alfred's demands in an agreement known as the Treaty of Wedmore.

Peace & Conversion

Three weeks after the surrender, in mid-June, Alfred returned to the Somerset marshes; this time, rather than hiding from Guthrum, he brought the Viking leader with him. The church at Aller, near Athelney – perhaps where Alfred prayed during his exile – was selected as the site for Guthrum's baptism. Here, Guthrum renounced the gods of Norse mythology, Odin, Thor, and Frigg, accepting Jesus Christ as his lord and saviour. Alfred, his baptismal sponsor and godfather, bestowed upon him a new Christian name, 'Aethelstan.'

In a single moment, the relationship between the two leaders transformed from mortal enemies to allies and brothers in Christ. The following week, they rode west to the royal estate of Wedmore, Somerset, embarking on 12 days of feasting to mark Guthrum's conversion and the war's end. What Guthrum thought about these ceremonies and agreements is unknown. He would, however, keep his word, retreating into Mercia in the autumn of 878 and then, the following year, to his own kingdom, East Anglia. He maintained good faith with Alfred, and in 886, they signed a second accord. Known to posterity as the Treaty of Alfred and Guthrum, the agreement regulated trade relations and legal disputes between their realms and divided the Kingdom of Mercia between the two leaders. It recognised Alfred as ruler of the West Midlands, where he won over the Mercian nobility after Ceolwulf II's death (or deposal) in 879. Guthrum, in turn, was acknowledged as ruler of the East Midlands, which had already been settled by Scandinavians.

Legacy

Alfred's victory greatly enhanced his authority, enabling him to radically reform the West Saxon state. Firstly, lords like Wulfhere of Wiltshire, who had sided with the invaders, were removed from office and replaced by those who had remained loyal to Alfred. The defences of Wessex were improved with a programme of burh (fortified town) building; the army was reformed, giving it greater mobility and a small fleet was built to patrol the southern coast.

Guthrum would live another four years, dying in 890. His successor in East Anglia, Eohric, neither embraced Christianity nor a cooperative relationship with Alfred. However, by the 890s, Wessex was quickly becoming a formidable stronghold, and future attacks from Guthrum's successors and new Viking fleets would be decisively repelled by Alfred's burhs and army.

This military system, under the leadership of Alfred's children, Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians (r. 911-918) and Edward the Elder (r. 899-924), allowed their dynasty to advance northward, conquering the Viking-settled lands of East Anglia and the East Midlands. By 927, Alfred's grandson, Aethelstan, had conquered Northumbria, thus extending West Saxon rule over all the formerly independent kingdoms, titling himself Rex Anglorum ('King of the English'). Such an expansion in power finds its origins in the victory at Edington. Indeed, today stands a monument on the battlefield, built in 2000, with the inscription: "To commemorate the Battle of Ethandun [Edington] fought in this vicinity May 878 when King Alfred the Great defeated the Viking army, giving birth to the English nationhood."