There was no compulsory state education for children in any of the western provinces of the Roman Empire. The primary sources are sparse when it comes to the education in Roman Spain, and while some scholars argue for a network of schools, others suggest that in the remoter areas of Spain sourcing Latin and Greek speaking teachers may have been difficult, and Roman education had geographical limitations.

Teachers in Roman Spain

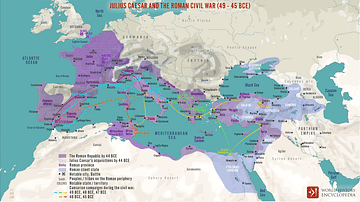

In 197 BCE, the Roman Republic divided the peninsula into Hispania Citerior (near) and Hispania Ulterior (far). In 27 BCE, Marcus Agrippa further divided the Ulterior region into Baetica (the modern-day Andalusia area) and Lusitania (the area of western Spain & part of modern-day Portugal).

Our sources indicate that Roman educational influence in these provinces was expanding sufficiently to require the services of teachers. The homogeneity in the style and content of education in the whole of the Roman Empire was striking; the same methods were used, and the same texts were worked on everywhere. Teaching was seen as a humble position; the average teacher was a man of lower social status who worked independently and had to maintain himself in a schooling system without any support from the Roman government. He worked for a low income, with which he had to also provide a teaching space, whether it was outdoors or beneath shelters or in hired rooms.

Inscriptions provide us with the evidence of the presence of the three principal categories of Roman educators:

- The magister or litterator provided an elementary Roman education for girls and boys aged 7-11 years old, which included reading, writing, mathematics, and languages.

- The grammaticus worked with boys aged 11-15 years old (in accordance with the role of women in the Roman world, girls generally finished their formal education at this age), teaching subjects such as Greek and Roman literature and philosophy and developing their writing, speech, and language skills.

- The rhetor trained students in subjects including public speaking, Roman law and politics; education at this level was only affordable for the upper classes, and it prepared a young boy for his future career and position in the higher echelons of Roman society.

Inscriptions confirm that in Baetica and Tarraconensis and other areas in the eastern and southern coasts of Hispania, children were learning with a grammaticus (CIL II. 5079). Roman studies for boys sometimes also continued with the rhetor.

Roman Schools in Hispania

When the Romans arrived after 219 BCE, the Turdetanians of Southern Iberia already possessed their own alphabet and their own literary tradition. Romans generally preferred to promote assimilation in conquered provinces through subtle means; by educating the sons of the elite, they would identify with the Roman cause. This ensured that these boys would better fill their future roles in provincial administration. The Latin language and a sound Roman education were necessary on different levels of society; knowledge of Latin was conducive to services and business and trade in the Roman world; once Roman rule was fully established, it was needed for everything.

However, although scholars agree that Roman authorities did not pursue a systematic educational policy across the provinces, it appears from some of the evidence available, that at times and in some places, authorities did become involved in education.

One of the first references to a school being set up in Hispania is from the Greek biographer, Plutarch (45/50 to 120/125 CE). Some academic commentary has viewed this establishment of a school as representative of the beginning of a network of schools in Hispania. The school was founded at Osca (modern Huesca) on the Hispanian side of the Pyrenees by the Roman general Quintus Sertorius (128-72 BCE). Up to this point, elementary schooling was either given by parents, or home tutors, or by independent teacher-owned 'schools'. It has been argued that Sertorius' intervention in establishing the school at Osca for the children of the Celtiberian chiefs was not with the intent of creating a school with the enlightened concept of offering educational advantages to the social elite. Roman education was a way of integrating local populations, but it appears Sertorius was operating for his own political purposes. Whatever Sertorius' intentions were, Plutarch comments that fathers would have been very pleased at seeing their sons in their purple-bordered togas receiving this prized Roman education. Modern commentary has pointed out that it also appears that Sertorius was able to provide teachers to give the desired education. The question is how common these teachers were at this time in the western provinces.

In 1st-2nd-century Tritium Megallum (modern-day Tricio in the northern region of La Rioja), a small but wealthy town in the area where the pottery terra sigillata hispanica was produced, the epigraphical record provides evidence that the authorities employed and paid 25-year-old Lucius Memmius Probus to fill the post of grammaticus latinus, teacher of Latin. This grammaticus latinus was employed for the education of children of the town's elite families. Memmius' main areas of teaching included criticism of poetry, basic history and elocution (CIL II. 2892). We learn from his funerary stone that he was a native of Clunia, 80 kilometers south of his place of employment. There is scholarly discussion over whether salaries were used to encourage teachers such as Memmius to take up positions in remote areas. Memmius' salary may have been generous; the salary is noted on his funerary stone, and while the exact amount is not clear, it was considered important enough to be recorded as part of his epitaph.

Once studies with a grammaticus were completed, boys moved on to further their education with a rhetor and subjects including public speaking, law, politics, and philosophy. There were some schools of rhetoric at Gades (modern-day Cádiz), Collippo, Lusitania, and Tarraco (modern-day Tarragona, Catalonia), the first of which was run by a professor from Baetica. Students from some wealthy families, at this time, may have opted to go to Rome for this part of their education.

At the end of the 1st or the beginning of the 2nd century CE, we have evidence of a school in Vipasca in the mining district of Aljustrel. In the Iberian peninsula, the Lex Vipasca, a law that dealt with the regulations around the mining community, exempted teachers from civic duties imposed by the chief official of the region. Modern scholarship suggests that this exemption may have been used to make working as a teacher in this area more attractive. The school in Vipasca may have been for the children of families working in the mines; we know that freeborn children were also employed in mining. The school was set up through the intervention of the authorities of the area, who may have viewed a rudimentary education, including the three Rs (reading, writing, and arithmetic), as beneficial. Some scholars argue that the example of a mining village such as Vipasca, with its own school, would not be an isolated case; there would have been others. This may be so, but specific references to schools in the areas of Lusitania and the interior regions of Iberia are very few, and we cannot know how prevalent schools were.

There is a paucity of evidence concerning Roman education, especially as we have noted, from areas further from the more Romanized eastern and southeastern coastal areas. However, literary and epigraphic sources indicate that many educated people originated from eastern and southern Iberia during the late Republic and the early Empire, and the high degree of literacy reflected in these men may imply that there were many schools in these particular regions. The Spanish city of Córdoba in Baetica is an example of advances in educational sophistication, a town in which there must have been a variety of educators. Córdoba had one of the longest histories of flourishing intellectual and artistic traditions outside of Italy; it was a deeply Romanized colony, which was made up of distinguished settlers and possessed the ius latii (Latin rights). It was probably only after the reign of the Roman emperor Vespasian (r. 69-79 CE), who took a particular interest in education, that other Roman towns in the Iberian Peninsula could boast of cultural accomplishments such as those attained by Córdoba, and these were mostly located in those more accessible regions of the two Iberian provinces of Baetica and Tarraconensis.

From Hispania to Rome

With the emergence of the Julio-Claudian dynasty at the beginning of the 1st century CE, people from Hispania began to appear in number at Rome. Many of these people received their early education in the Spanish provinces. Literary sources referring to the level of education they possessed illustrate that Roman education in the Iberian peninsula was sufficiently successful to the point that it allowed many people born in the provinces to take advantage of their education and to become a part of society in Rome.

Foremost among them were members of the Annaei of Córdoba. As a family, the Annaei were prolific writers, and they became the patron family for many of their educated compatriots and friends who either moved to Rome on their own or were attracted there by the Annaeus family. The patriarch of the Annaei, L. Annaeus Seneca – better known as Seneca the Elder (54 BCE to c. 39 CE), author and father of philosopher Seneca the Younger – attended his early schooling up to grammaticus level in Córdoba. He attended, we are told, with more than 200 pupils, a considerable number. Seneca in his writings provides us with evidence of rhetors in Hispania: Porcius Latro, Gavius Silo, and Clodius Turrinus (Controv. a praef. 3.10:10 praef. 14,16). Seneca completed his own advanced studies in Rome, moving between homes in the cities of Córdoba and Rome afterwards. Seneca's son, Seneca the Younger (c. 4 BCE to 65 CE), was born in Córdoba, and at the age of 10, he went with his father to continue his education in Rome.

Another famous figure educated in Spain and who chose to go to Rome was the poet Martial (c. 38/41 to c. 101/104 CE), a self-confessed Celtiberian (Mart. 10.65). He was born in Bilbilis in Tarraconensis and moved to Rome as a young man to pursue a literary career. Finally, perhaps the most famous of all, Marcus Ulpius Traianus (53-117 CE), came from the city of Itálica in Hispania, where he would have received a full Roman education suited to his social rank. Trajan (r. 98-117 CE) became the first emperor born outside of Italy.