Fear of Insurrection comes from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl (1861) by Harriet Jacobs (l. c. 1813-1897) describing the reaction of the White community of Edenton, North Carolina, to news of Nat Turner's Rebellion in Southampton County, Virginia, in August of 1831. The events described were repeated in other slave-holding states at the same time.

Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl is Jacobs' autobiography, written by herself, detailing her life as a slave in Edenton, North Carolina, her escape to the north, and her work as an abolitionist. In this chapter, referring to events in the fall of 1831 while she was still a slave, Jacobs describes how the slave-holding community and poor Whites, fearing the Blacks might be planning an insurrection like Turner's, attacked them, searching their houses for evidence of revolt, and manufacturing that evidence when none was found.

Although Nat Turner's Rebellion is well-documented, and reports of events like the one below are attested, there are few that relate the details of retaliation against slaves and free Blacks following Turner's revolt, and none as detailed as Jacobs' description of the helpless situation of Blacks throughout the South in the fall of 1831. Fear of Insurrection, like the rest of Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, is understood as an important primary document on the life of a slave in the United States of the 19th century written by someone who lived it.

Turner's Rebellion & Reaction

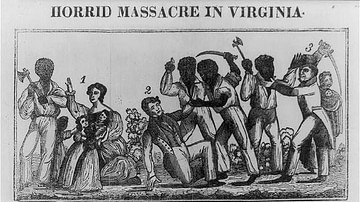

Nat Turner's Rebellion (also known as the Southampton Insurrection) of 21-23 August 1831 was led by the educated slave and preacher Nat Turner (l. 1800-1831) and resulted in the deaths of at least 55 White people and 120 Blacks (no doubt more) in Southampton County, Virginia.

The revolt, the deadliest slave uprising in US history, terrified Whites in Virginia and other slave-holding states, who responded by instituting harsher slave laws, searching the homes of free Blacks and the quarters of slaves for weapons or "seditious reading material", and torturing slaves and free Blacks in hopes of wringing a confession from them that would betray any plans of a similar uprising.

At the time these persecutions were going on, Nat Turner was still at large. No one knew whether Turner had acted alone or if his revolt was part of a larger conspiracy. Gabriel's Rebellion of 1800 in Virginia, led by Gabriel Prosser (l. c. 1776-1800), sought to free all the slaves in Virginia and inspire uprisings elsewhere, with the ultimate goal of freeing all the slaves in the United States, and Denmark Vesey's Conspiracy (1822) in South Carolina had also been widespread and carefully planned. As far as the slave-holding community knew in the fall of 1831, Turner's rebellion might only be the opening salvo of an even larger insurrection, and other states might soon experience what Virginia had in Southampton County.

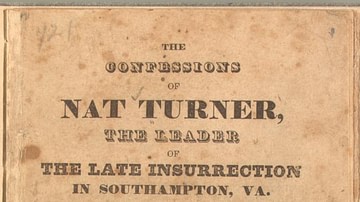

Turner was finally captured on 30 October 1831 and, while awaiting trial, granted an interview to the lawyer T. R. Gray (l. c. 1800 to c. 1834), which was published in November 1831 as The Confessions of Nat Turner. Once he was apprehended, it became clear he was the leader of the revolt, had acted alone, and there was no need to fear a wider conspiracy.

Between 23 August and 30 October, however, the slave-holding states lived in a kind of trembling expectation of what they felt sure would be the next phase of Turner's uprising and made the lives of their slaves and those of free Blacks a daily threat of beatings without provocation, searches of homes and persons, restriction of travel and gatherings, and indiscriminate murders.

Text

The following is taken from Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl by Harriet Jacobs, Chapter XII, pp. 55-59 of the Dover Thrift Edition, 2001.

NOT far from this time Nat Turner's insurrection broke out; and the news threw our town into great commotion. Strange that they should be alarmed when their slaves were so "contented and happy"! But so it was.

It was always the custom to have a muster every year. On that occasion every white man shouldered his musket. The citizens and the so-called country gentlemen wore military uniforms. The poor whites took their places in the ranks in every-day dress, some without shoes, some without hats. This grand occasion had already passed; and when the slaves were told there was to be another muster, they were surprised and rejoiced.

Poor creatures! They thought it was going to be a holiday. I was informed of the true state of affairs and imparted it to the few I could trust. Most gladly would I have proclaimed it to every slave; but I dared not. All could not be relied on. Mighty is the power of the torturing lash.

By sunrise, people were pouring in from every quarter within twenty miles of the town. I knew the houses were to be searched; and I expected it would be done by country bullies and the poor whites. I knew nothing annoyed them so much as to see colored people living in comfort and respectability; so I made arrangements for them with especial care.

I arranged everything in my grandmother's house as neatly as possible. I put white quilts on the beds and decorated some of the rooms with flowers. When all was arranged, I sat down at the window to watch. Far as my eye could reach, it rested on a motley crowd of soldiers. Drums and fifes were discoursing martial music. The men were divided into companies of sixteen, each headed by a captain. Orders were given, and the wild scouts rushed in every direction, wherever a colored face was to be found.

It was a grand opportunity for the low whites, who had no negroes of their own to scourge. They exulted in such a chance to exercise a little brief authority and show their subserviency to the slaveholders; not reflecting that the power which trampled on the colored people also kept themselves in poverty, ignorance, and moral degradation.

Those who never witnessed such scenes can hardly believe what I know was inflicted at this time on innocent men, women, and children, against whom there was not the slightest ground for suspicion. Colored people and slaves who lived in remote parts of the town suffered in an especial manner. In some cases, the searchers scattered powder and shot among their clothes, and then sent other parties to find them, and bring them forward as proof that they were plotting insurrection.

Everywhere, men, women, and children were whipped till the blood stood in puddles at their feet. Some received five hundred lashes; others were tied hands and feet, and tortured with a bucking paddle, which blisters the skin terribly. The dwellings of the colored people, unless they happened to be protected by some influential white person, who was nigh at hand, were robbed of clothing and everything else the marauders thought worth carrying away.

All day long these unfeeling wretches went round, like a troop of demons, terrifying and tormenting the helpless. At night, they formed themselves into patrol bands, and went wherever they chose among the colored people, acting out their brutal will. Many women hid themselves in woods and swamps, to keep out of their way. If any of the husbands or fathers told of these outrages, they were tied up to the public whipping post, and cruelly scourged for telling lies about white men. The consternation was universal. No two people that had the slightest tinge of color in their faces dared to be seen talking together.

I entertained no positive fears about our household, because we were in the midst of white families who would protect us. We were ready to receive the soldiers whenever they came. It was not long before we heard the tramp of feet and the sound of voices. The door was rudely pushed open; and in they tumbled, like a pack of hungry wolves.

They snatched at everything within their reach. Every box, trunk, closet, and corner underwent a thorough examination. A box in one of the drawers containing some silver change was eagerly pounced upon. When I stepped forward to take it from them, one of the soldiers turned and said angrily, "What d'ye foller us fur? D'ye s'pose white folks is come to steal?"

I replied, "You have come to search; but you have searched that box, and I will take it, if you please."

At that moment, I saw a white gentleman who was friendly to us; and I called to him and asked him to have the goodness to come in and stay till the search was over. He readily complied. His entrance into the house brought in the captain of the company, whose business it was to guard the outside of the house and see that none of the inmates left it.

This officer was Mr. Litch, the wealthy slaveholder whom I mentioned, in the account of neighboring planters, as being notorious for his cruelty. He felt above soiling his hands with the search. He merely gave orders; and, if a bit of writing was discovered, it was carried to him by his ignorant followers, who were unable to read.

My grandmother had a large trunk of bedding and table cloths. When that was opened, there was a great shout of surprise; and one exclaimed, "Where'd the damned niggers git all dis sheet an' table clarf?"

My grandmother, emboldened by the presence of our white protector, said, "You may be sure we didn't pilfer 'em from your houses."

"Look here, mammy," said a grim-looking fellow without any coat, "you seem to feel mighty gran' 'cause you got all them 'ere fixens. White folks oughter have 'em all."

His remarks were interrupted by a chorus of voices shouting, "We's got 'em! We's got 'em! Dis 'ere yaller gal's got letters!"

There was a general rush for the supposed letter, which, upon examination, proved to be some verses written to me by a friend. In packing away my things, I had overlooked them. When their captain informed them of their contents, they seemed much disappointed. He inquired of me who wrote them.

I told him it was one of my friends. "Can you read them?" he asked. When I told him I could, he swore, and raved, and tore the paper into bits. "Bring me all your letters!" said he, in a commanding tone. I told him I had none. "Don't be afraid," he continued, in an insinuating way. "Bring them all to me. Nobody shall do you any harm."

Seeing I did not move to obey him, his pleasant tone changed to oaths and threats. "Who writes to you? Half free niggers?" inquired he. I replied, "O, no; most of my letters are from white people. Some request me to burn them after they are read, and some I destroy without reading."

An exclamation of surprise from some of the company put a stop to our conversation. Some silver spoons which ornamented an old-fashioned buffet had just been discovered. My grandmother was in the habit of preserving fruit for many ladies in the town, and of preparing suppers for parties; consequently, she had many jars of preserves. The closet that contained these was next invaded, and the contents tasted. One of them, who was helping himself freely, tapped his neighbor on the shoulder, and said, "Wal done! Don't wonder de niggers want to kill all de white folks, when dey live on 'sarves" [meaning preserves]. I stretched out my hand to take the jar, saying, "You were not sent here to search for sweetmeats."

"And what were we sent for?" said the captain, bristling up to me. I evaded the question.

The search of the house was completed, and nothing found to condemn us. They next proceeded to the garden, and knocked about every bush and vine, with no better success. The captain called his men together, and, after a short consultation, the order to march was given. As they passed out of the gate, the captain turned back, and pronounced a malediction on the house. He said it ought to be burned to the ground, and each of its inmates receive thirty-nine lashes. We came out of this affair very fortunately; not losing anything except some wearing apparel.

Towards evening the turbulence increased. The soldiers, stimulated by drink, committed still greater cruelties. Shrieks and shouts continually rent the air. Not daring to go to the door, I peeped under the window curtain. I saw a mob dragging along a number of colored people, each white man, with his musket upraised, threatening instant death if they did not stop their shrieks.

Among the prisoners was a respectable old colored minister. They had found a few parcels of shot in his house, which his wife had for years used to balance her scales. For this they were going to shoot him on Court House Green. What a spectacle was that for a civilized country! A rabble, staggering under intoxication, assuming to be the administrators of justice!

The better class of the community exerted their influence to save the innocent, persecuted people; and in several instances they succeeded, by keeping them shut up in jail till the excitement abated. At last, the white citizens found that their own property was not safe from the lawless rabble they had summoned to protect them. They rallied the drunken swarm, drove them back into the country, and set a guard over the town.

The next day, the town patrols were commissioned to search colored people that lived out of the city; and the most shocking outrages were committed with perfect impunity. Every day for a fortnight, if I looked out, I saw horsemen with some poor panting negro tied to their saddles and compelled by the lash to keep up with their speed, till they arrived at the jail yard.

Those who had been whipped too unmercifully to walk were washed with brine, tossed into a cart, and carried to jail. One black man, who had not fortitude to endure scourging, promised to give information about the conspiracy. But it turned out that he knew nothing at all. He had not even heard the name of Nat Turner. The poor fellow had, however, made up a story, which augmented his own sufferings and those of the colored people.

The day patrol continued for some weeks, and at sundown a night guard was substituted. Nothing at all was proved against the colored people, bond or free. The wrath of the slaveholders was somewhat appeased by the capture of Nat Turner. The imprisoned were released. The slaves were sent to their masters, and the free were permitted to return to their ravaged homes. Visiting was strictly forbidden on the plantations.

The slaves begged the privilege of again meeting at their little church in the woods, with their burying ground around it. It was built by the colored people, and they had no higher happiness than to meet there and sing hymns together and pour out their hearts in spontaneous prayer. Their request was denied, and the church was demolished.

They were permitted to attend the white churches; a certain portion of the galleries being appropriated to their use. There, when everybody else had partaken of the communion, and the benediction had been pronounced, the minister said, "Come down, now, my colored friends." They obeyed the summons, and partook of the bread and wine, in commemoration of the meek and lowly Jesus, who said, "God is your Father, and all ye are brethren."