Eritrea, located on the Red Sea coast of the Horn of Africa, was the ‘firstborn’ colony of Italy. The potential of a trade centre and naval base at Assab first attracted Italian interests in 1869. The Kingdom of Italy, however, did not officially institute the 'Colony of Eritrea' until 1890.

Italy's interest in Eritrea revived under Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) who was determined to raise Fascist Italy to the status of the other Great Powers. The colony was then used as a springboard for the invasion of Ethiopia in 1935-36. Eritrea became a part of Italian East Africa and was the most enduring Italian colony until it was occupied by the British in 1941. Eritrea was subsequently absorbed into Ethiopia and did not gain independence until 1991.

Why Did Italy Choose Eritrea?

During the age of imperialism (traditionally identified between 1870 and 1914) many European powers extended their political, military, and economic control over a large part of the world. In this context, Italy was a latecomer: while other countries were trying to valorise their possessions, Italy was still launching itself into new conquests. The first Italian colony, Eritrea, was officially constituted only in 1890, but it was a formal declaration that followed 21 years of Italian presence in the area.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 had an important impact on the trajectory of Italian colonialism. The Canal connected the Mediterranean Sea to the Indian Ocean through the Red Sea, thus reshaping global maritime trade and facilitating connections between European empires and their colonies. These are the reasons why many countries began to establish and reinforce their bases along the coasts of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden. Great Britain had already occupied Aden in 1839 and Perim island in 1857, later part of the Aden Protectorate (1872-1963); France was already in what would become the French Somaliland (1884-1967); Egypt had controlled Sudan since 1820, and in 1865 it obtained from the Ottoman Empire (of which Egypt was formally a part) the port of Massawa. The Red Sea promptly became one of the most hotly contested geopolitical areas in the world.

What is now known as Eritrea was then a territory that had been disputed by various powers for its strategic position. The area had formally been under the control of the Ethiopian Empire, as a subordinate kingdom named Medri Bahri, and then part of the Ottoman Empire. Ottoman control was only nominal, and parts of the region were still governed by local entities, like the Sultanate of Aussa.

The new opportunities offered by the Canal titillated the ambitions of Giuseppe Sapeto (1811-1895), a former priest who had been as a missionary in the Horn of Africa in the first half of the 19th century. Sapeto elaborated a project for a seaport in the Red Sea which could secure Italian trade. The project came to the attention of the Italian government, led by Luigi Menabrea (1809-1896). Sapeto’s dreams were seen favourably both by the Italian Crown and by groups of merchants and ship makers in northern Italy. This support led the government to entrust Sapeto with the mission to explore the coasts of the Red Sea to purchase a suitable naval base for Italy. After having discarded two places along the Arab coast, Khur Amera and Sheikh Said, because they were already occupied, the mission moved towards the African coast. The final choice fell to Assab, a small fishing village. On the 15th November 1869, Sapeto signed a convention with the commitment to buy the bay of Assab with the two self-proclaimed sultans of Raheita, the brothers Ibrahim and Hassan ibn Ahmad.

The Involvement of the Italian Government & British Support

The Italian government did not want to get directly involved in this colonial adventure. Both the prime minister Menabrea and his successor Giovanni Lanza (1810-82) feared provoking a reaction from other, more powerful countries. The government appealed to the shipowner Raffaele Rubattino (1810-1881), asking him to acquire the bay in his name, under the pretext of making it a private commercial base. On the 11th March 1870, Rubattino concluded the agreement. Thus begins Italian colonialism in Africa. As it turned out, for eight years Assab was abandoned: Rubattino had no interests in maintaining the base and the various governments through the 1870s found no particular use for this micro-colony. At the same time, Egypt did not remain passive to this Italian intrusion in the Horn of Africa. Only a few days after the departure of Sapeto, Egyptian troops entered the bay in protest over the occupation. However, Rubattino had to deal with Assab once again: after the refusal of the Italian Chamber of Deputies to finance his project for a prolongment of a maritime line, he then tried to convince the government that Assab could be useful to converge Ethiopian trade there and transform it into a major port. The new government led by Benedetto Cairoli (1825-1889) encouraged an expedition for the reoccupation of Assab. Cairoli did not inform the Parliament, but instead aimed at gaining the approval of the United Kingdom. Rubattino, escorted by a British gunboat, arrived in Assab and signed a new agreement – again under his name - with the local sultan on the 15th March 1880.

But why had the British intervened? A new phase for Italian colonialism was opened after the Berlin Congress (1878), which had undermined the integrity of the Ottoman Empire, leading to renewed French efforts in the Mediterranean, and this was followed by new colonial ambitions from Germany. During the 1880s, London was overburdened by its commitments as a global power, so it decided to rely on a junior partner in the Horn of Africa that could avoid German or French intrusions. As a matter of fact, it was thanks to ‘benevolent’ British approval that on the 10th March 1882, the Italian government took over Assab, thereby becoming an official Italian possession and no longer a private property. The official involvement of Italy marked the beginning of a much bolder colonial policy. This was again a consequence of the international situation at the time. In 1881, France imposed a protectorate over Tunisia, an area which had always been an objective of Italian colonial aspirations. The frustration for the so-called ‘slap of Tunis’, together with the new wave of European colonialism pushed by the Berlin Conference (1884-1885) which both formalised and regulated the ‘scramble for Africa’, encouraged Italian expansion. In addition, Egypt was obliged to loosen its ties to the Horn of Africa, because of its involvement in the Mahdist uprising – a revolution led by an Islamic movement that sought to overthrow the Egyptian control of Sudan and then to start a war that involved the Horn of Africa (1881-99).

The First Clash with Ethiopia

Still benefitting from the British benevolence, the prime minister Pasquale Stanislao Mancini (1817-88) ordered in 1885 the occupation of the city of Massawa, a port on the Red Sea. In reality, Mancini’s project was much more ambitious. Mancini was convinced that an Italian involvement in the Red Sea could represent the "key to the Mediterranean" (Mancini, 1885): the dream of an Anglo-Italian cooperation in Sudan was the first step in Mancini's plan to extend an Italo-British cooperation in the Mediterrenean Sea. The meagre results of the subsequent military expedition caused the fall of Mancini’s government, which had been strongly criticised in Parliament for the uselessness of the operation. Nonetheless, Italian troops in Africa maintained a hostile attitude, seizing a series of villages in an action that was considered a threat by their neighbour, the Ethiopian Empire.

Abyssinia, as the Ethiopian Empire was frequently known as, had always been underestimated by Italy. At the time it was led by Negus (emperor) Yohannes IV (1837-89), who was facing both the Mahdist war on the frontier with Sudan and internal turbulences. One of the most important vassals of the Empire, the King of Shewa Menelik (1844-1913), was considered by the Italians to be one of their allies inside Ethiopia, capable of undermining the Negus’ authority and internal cohesion.

Nevertheless, Ras Alula (1847 – 1897), one of the most powerful Ethiopian military leaders and governor of the province where Italians troops had started the offensive, attacked and annihilated in Dogali a battalion of 500 Italian soldiers on 27 January 1887. Even though the operation was entirely a personal initiative of Ras Alula, Italy decided to respond with a military expedition against Ethiopia. 20,000 men under the command of Alessandro di San Marzano (1830-1906) were deployed in 1887. In the meantime, the diplomat Pietro Antonelli (1853-1901) signed a secret treaty of neutrality with Menelik, hoping to weaken the Ethiopian position. Despite the mobilisation, the war took an unexpected turn, because Yohannes decided to withdraw his army, even if bigger than the Italian counterpart, in order to face the Mahdists. This move cost Yohannes his life, as the emperor died in the battle of Gallabat of 1889.

The death of Yohannes IV opened the fight for his succession to the throne, which was claimed by two parties. Mangesha Yohannes had been nominated heir by a dying Yohannes and he was supported by Ras Alula. The rival claimant was Menelik, who was supported by the Italians and who had the allegiance of the majority of Ethiopian dignitaries. Menelik won the dispute and was crowned in 1889. Italy signed with the new emperor the Treaty of Wuchale (1889) which hoped to promote good relations and trade between Italy and Ethiopia. However, the treaty represented the cause of one of the most important clashes between the two countries, because the Italians claimed that the treaty established a protectorate over Ethiopia. The misunderstanding, whether intentional or not, derived from a difference in the interpretation between the Amharic and Italian translation of the text over article 17, which allowed Ethiopia to make use of Italy for the purposes of international diplomacy.

The Birth of the Colony & the Battle of Adwa

In the meantime, the Italian prime minister Francesco Crispi (1818-1901) strongly advocated for a more important role for Italy amongst the great powers. His unscrupulous foreign policy combined an increasing militarisation with colonial activism. In this regard, Crispi was the first one to provide a justification for Italian expansionism, namely the necessity to combine expansionist policies with emigration. In those years characterised by a mass migration of southern Italians to the north of Italy, Africa could provide an alternative source of land for poor farmers. The link between colonialism and emigration would be resumed later by Fascism, with its leader Benito Mussolini emphasising the search for ‘a place under the sun’ for Italy. Returning to Crispi, in 1890 he officially instituted the Eritrean Colony, with Massawa as its capital. The name Eritrea was inspired by the ancient Greek name of the Red Sea, Erythra.

In the event, Menelik was able to avoid any interference from Italy, and in 1893 he denounced the Italian claim of a protectorate over his empire. Italian control had expanded to the cities of Asmara and Cheren, and its influence was projected inside Ethiopia, in the region of Tigray. The new governor of Eritrea, General Baldassarre Orero (1841-1914), was so confident of the weakness of Abyssinia that he decided to march towards the city of Adwa, which held a particular religious importance for the Ethiopian Orthodox Church, the main denomination in Ethiopia. For this unauthorized initiative Orero was dismissed and replaced by General Antonio Gandolfi (1835 -1902), then followed by a close friend of Crispi, Oreste Baratieri (1841-1901). Baratieri's ambitions, however, were bigger than the troops at his disposal, and he provoked the powerful neighbour with several military expeditions beyond their border. The new governor believed that with a quick occupation of the Tigray he could threaten the stability of the Ethiopian Empire, and in 1895 he began the invasion. The situation quickly got out of hand: the Ethiopian leaders allied with Italy withdrew, confusion reigned among the military commands, and the Italian troops began to suffer significant losses.

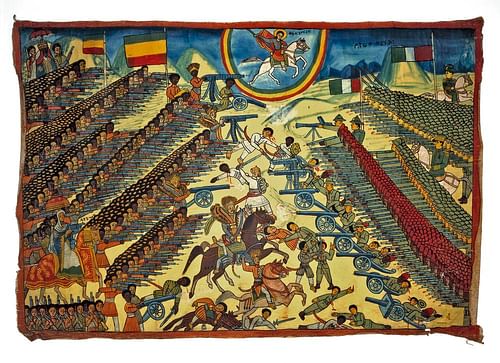

On 1 March 1896 the unthinkable happened: on the battlefield of Adwa Italian troops were heavily defeated, with around 6,000 deaths and more than 3,000 soldiers captured. It was the worst defeat of a European army in the whole history of colonialism. What followed was a political earthquake: Crispi’s cabinet collapsed, Ethiopia secured decades of full sovereignty after a battle that became a symbol for Africans and black people in general. The battle also became a collective trauma for Italy, paving the way to revanchist sentiments that culminated with the fascist invasion of Ethiopia in 1935.

Managing the Colony

The colony of Eritrea became something of a colonial backwater. The colony was assigned to Ferdinando Martini (1841-1928) – the first civilian governor – with the precise task of making Italians forget Eritrea. Despite the downgrading, Martini started to rebuild the colony from 1898, writing the first Ordinamento, a code for Eritrea that subordinated the military power to the civil authority, elaborating an annual budget, and trying, without great success, to start investments for infrastructures in the colony. In the shadow of the general disinterest for Eritrea, the personalities of the governors started to emerge. The paternalistic government of Martini, who identified himself with the colony to the point of writing "I am the colony" (Martini, 328), did not change the relationship with the colonial subjects, towards whom he used an iron fist if they did aligned with him. Relations with Ethiopia did improve. Menelik, after having broadened the international relations of Ethiopia and centralised power, enjoyed good relations with Martini, who preferred to pursue a good neighbour policy towards Ethiopia instead of seeking revenge. However, Menelik’s health was declining, and many countries feared a tense transition after his imminent death. In 1906 the UK, Italy, and France signed a Tripartite Treaty which basically drew their respective areas of influence within Ethiopia.

The following years saw few changes in Eritrea, despite a renewed assertiveness in the Italian public debate due to the development of a colonial lobby in Italy, that aimed to prepare and mobilize public opinion. The Italian invasion of Libya in 1911 and the First World War (1914-18) even slowed down the evolution of the colony as the best troops were sent away to combat and the lack of manpower blocked any infrastructural development. The aftermath of the Great War represented a large disappointment for Italy which had hoped to receive colonial compensation under the The Treaty of Versailles of 1919. A dramatic change of style arrived with Mussolini, who assigned particular relevance to colonial issues. Mussolini was intent on trying to present Italy as a great power and he wanted to avenge the humiliation of Versailles.

This new posture greatly encouraged those colonial officials such as Jacopo Gasparini (1879-1941), governor of Eritrea since 1923, a year after the seizure of power by Fascism. Gasparini promoted a personal diplomatic effort towards Yemen, led since 1918 by the Imam Yahya (1869-1949), who was in open opposition to the British protectorate of Aden. Gasparini gained the Imam’s sympathy and was able to secure a treaty with Yemen in 1926 that made Italy its most important political and economic partner. The British feared that Italy could create its own ‘Suez Canal’ between the coasts of Eritrea and Yemen, which was conducting wars in the Arabian Peninsula thanks to the purchase of Italian weapons. Plans for a more autonomous Eritrea, becoming a centre of irradiation of Italian policies in the Red Sea and in the Horn was soon stopped by Rome, for the fear that this could compromise the then good relations between Fascist Italy and Great Britain. From this point onwards, Eritrea’s role was re-oriented exclusively as the base for the launch of an attack and subsequent occupation of Ethiopia in 1936.

Italian Colonialism & Eritrean Identity

An important aspect that describes the relation between the coloniser and the colonised was the role of indigenous troops. The Ascari, Eritrean troops at the service of Italy, gave fundamental support in many military campaigns, as they fought in Libya, Somalia, and Ethiopia. Nevertheless, they were prevented from rising through the ranks of the army. With the occupation of Ethiopia in 1936, Eritrea, together with Italian Somaliland, became part of Italian East Africa (Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI). In Mussolini’s plan, Eritrea was destined to become the industrial heart of the AOI. Between the 1920s and 1930s there was an impressive transformation of the colony, with an expansion of the immigration of Italians settlers. By 1945, after the capitulation of Italian colonies, there were almost 40,000 Italians left in Eritrea. The city of Asmara, the current capital of Eritrea, was reshaped as a ‘little Rome’, with a process of urbanization and modernization characterised by a Modernist architectural style that was declared in 2017 a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The firstborn colony, however, was the first one to be attacked by the British during the Second World War (1939-45). In 1941, after the fall of the city of Cheren, Eritrea was soon occupied by British troops, who kept a military administration there until 1949 and then an UN-sponsored protectorate until 1952, when Eritrea was assigned to Ethiopia. Decades of Italian colonisation, with racial policies that split groups and with the creation of an artificial boundary between Ethiopia and Eritrea, led to a difficult cohabitation. Italian colonialism had undoubted repercussions on the formation of an Eritrean identity. After a failed attempt at federalisation, Eritrea was transformed into an Ethiopian province, and since the 1960s the region was characterised by a continuous state of warfare that culminated in 1991 with the independence of Eritrea.