The Red Army of the USSR began the Second World War (1939-45) with a series of shocking defeats, but from late 1942, it rallied and held on to key cities like the capital Moscow, Leningrad (Saint Petersburg), and Stalingrad (Volgograd). Then, through 1943 to the war's end, the Red Army accumulated a string of major victories such as the battles of Smolensk, Kursk, and Berlin, which saw the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945.

Formation & Evolution

The Soviet Union's Red Army was formed in 1918 following the Bolshevik October Revolution of 1917, which swept away the rule of the tsars. The Red Army was officially called the RKKA or Red Army of Workers and Peasants (Raboche-Krest'yanskaya Krasnaya Armiya), red being the colour most associated with Bolshevism. It officially became the Soviet Army in 1944.

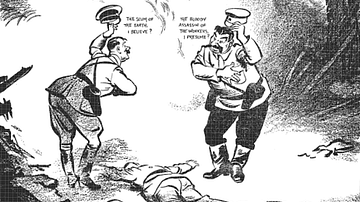

The Red Army was immediately required to fight the White Army, that is, supporters of the monarchy and anti-Bolsheviks, in a fierce civil war (1917-22). The Bolshevik victory in this war was achieved thanks to the increasing professionalism of the Red Army. The move from a revolutionary militia to a professional national army is credited to Leon Trotsky (1879-1940) and the incorporation of around 48,000 officers and over 200,000 non-commissioned officers from the old imperial army.

In its daily operations, the Red Army was heavily influenced by the ideas of Bolshevism. For example, the word 'officer' was prohibited and only reinstated in 1935. Rather, the term 'commander' was used, and each commander was obliged to report to a political commissar, who would give their approval to the commander's orders. This dual system was weakened considerably through practical realities and by the demands of WWII, when most commanders were left to make military decisions while the commissars restricted themselves to political instruction and party work. When the USSR was attacked by Nazi Germany in June 1942 (Operation Barbarossa), the dual system was revived somewhat before weakening again as the war progressed. Nevertheless, there remained, throughout the conflict, tensions between these two different groups of command personnel.

The leader of the USSR from 1924 was Joseph Stalin (1878-1953), and he harboured a serious distrust of his own army, especially when he thought it was supporting his chief political rival Nikolai Bukharin (1888-1938). For this reason, Stalin purged the Red Army:

Some 35,000 officers out of an officer corps of roughly 80,000 fell victim to the purges; among them three of the five Marshals of the Soviet Union, all eleven deputies of the commissar for war, 75 of the 85 corps commanders, and 110 out of the 195 divisional commanders were killed.

(Dear, 962)

In 1941, seeing the damage he had done to the Red Army's ability to actually function, Stalin brought back around 4,000 officers who had been sent to prison camps.

Recruitment

With the increasing threat from Nazi Germany, in 1939 Stalin had decreed all male Soviet citizens could be drafted into the armed forces (18 to 36 years old). Conscripts primarily came from Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus until these areas became part of the battlefield in 1941. As the war went on, recruits also came from Central and Eastern Russia, and there were 'national' divisions made up of Lithuanians, Uzbekis, and Armenians, for example. The 'national' divisions typically had Russian officers. Mountain units had a strong contingent from Georgia. There were also penal battalions made up of convicts (including political prisoners), which in total numbered around 440,000 men.

Women had long performed non-combatant roles in the Red Army and were ever-present as doctors and medics. After the start of WWII, women were also involved in combatant roles, particularly anti-aircraft units. There were also many women snipers (who were volunteers) and tank drivers (some were even tank unit commanders). In all, "at least 800,000 women served in Soviet forces during the war" (Rees, 162).

In 1939, the Red Army had 3 million members but was growing fast. The Red Army was split into two parts, one in the West and one in the East to face the threat from Nazi Germany and militarist Japan respectively. This split was because the USSR's poor transport network could not then permit the easy movement of armies across such vast areas. Although the importance of technology was acknowledged, there remained a strong bias towards infantry as the best means to win battles.

Command Structure & Organisation

During WWII, the command of the Red Army was in the hands of Stalin, the supreme commander-in-chief. Below Stalin but also including him was the State Committee for Defence (GKO), which included such figures as the foreign minister, Vyacheslav Molotov (1890-1986), the defence minister, Marshal Kliment Voroshilov (1881-1969), and the head of state security, Lavrentiy Beria (1899-1953). Membership was select and changed depending on performance. Below the GKO was the Stavka, a council consisting of Stalin, a chief of staff, and a few other experienced generals. The Army General Staff worked with the Stavka as its planning and executive agency. The Stavka only met when Stalin decided it should, and as the war went on, its meetings became rarer. From 1942, Stalin appointed his best general, Georgy Zhukov (1896-1974), as deputy commander-in-chief. During WWII, each army front (aka army group) was commanded by its own war council.

A typical Soviet army group was made up of infantry (known as Riflemen or Streltsy), artillery (which included anti-aircraft guns), cavalry (based on the old famed Cossack units and still wielding sabres), and mechanised corps (which included tanks and motorised rifle divisions). Throughout the war, the Red Army lacked a dedicated armoured infantry carrier vehicle; instead, motorised rifle troops were expected to hitch a ride on a tank. Units that performed well often won the right to have a 'Guards' prefix before their name, a distinction which brought the unit better pay, clothing, and equipment. The elite Red Army units were the Scouts (Razvedchiki), who were recruited from the best soldiers in a division.

Red Army Uniforms

The standard infantry uniform was the simple drab khaki-coloured gymnastyorka jacket with trousers that flared at the hips and either high or low leather boots. The uniform came in two versions, light cotton for summer and a heavy wool for winter. In colder weather, a padded jacket (telogreika), great coat, or sheepskin coat (shuba) was worn. The coat was rolled up and worn across the back and one shoulder in warmer weather. The Scouts were distinguishable by their camouflage coveralls. Camouflage in winter was provided by white hooded coveralls. Tank units had more specialised uniforms, typically black coveralls and a leather jacket. The Model 1940 steel helmet and pilotka sidecap (enlisted soldiers) and peaked cap (officers) were standard, replaced by a fur hat (shapka ushanka) in winter conditions.

Badges of rank and insignia were rather subdued on Red Army uniforms in keeping with its proletarian ethos. There were no shoulderboards prior to 1943, for example, and rank was indicated by discreet stars, diamonds, rectangles, or triangles in enamelled metal attached (or embroidered onto) collars or one arm of a greatcoat. The top rank of marshal was indicated by a star and wreath, while, at the other end of the scale, a junior sergeant wore a single triangle. Perhaps because of the austerity of the uniform, soldiers frequently wore medals awarded for bravery on their battledress.

Weapons

The USSR had rearmed significantly in the early 1930s, but this meant that by 1941 many tanks, in particular, were greatly inferior to those of the German Army. The Red Army did at least have a large number of tanks as this had been a priority area.

Initially, Soviet tanks tended to be light on armour, and they suffered from a chronic lack of spare parts. From 1942, things improved considerably. The 26-ton T34 medium tanks were produced in greater numbers. These tanks were superior to any the Axis armies fielded and could resist most anti-tank guns. In summary, the T34 "had a simple diesel engine (500 hp), good armour, excellent firepower, and superb mobility in snow and mud" (Boatner, 702). The T34 had a 76-mm (2.9 inch) gun and sloping armour 44 mm (1.75 in) thick, which could resist even the most powerful of Axis guns. The T34 tank and other excellent models like the slower but well-armoured KV heavy tank series also started to be used in larger and much more effective battle groups from 1942 onwards.

The Red Army's artillery was a weakness as war broke out since top commanders had thought, unwisely, that this type of weaponry had had its day and modern warfare would be much more mobile. However, artillery gradually became a great strength of the Red Army, with entire artillery divisions formed, which combined mine-throwers, howitzers, and rocket launchers for offensive operations, and specialised divisions for defence only, which had howitzers and field guns. Artillery weapons typically came in three calibres: 76, 122, and 152 mm.

A very effective Soviet weapon was the BM-13 Katyusha rocket launcher, known as 'Stalin's Organ'. Mounted on a truck, this weapon could rapidly fire 16 132-mm solid-fuel rockets. One German soldier remembered that this weapon was "the most terrible and shocking thing I have ever encountered" (Stahel, 299). As artillery units became stronger towards the end of the war, there were "often up to 375 guns and mortars on a kilometre of front – a truly earth-shaking barrage" (Zaloga, 21).

The PPSh-41 submachine gun, with its distinctive circular magazine of 71 rounds, became a symbol of the Red Army's infantry. The weapon was produced in very large numbers, over 6 million during WWII. 34% of the Red Army infantry carried a machine gun, a high figure compared to just 11% for the German Army's infantry. Rifles were more accurate but were more expensive to produce and required more skill to fire than submachine guns, a weapon which had a distinct advantage at close quarters. Finally, the 7.62-mm Maxim Model 1910 machine gun, with its distinctive trolley wheels, was a useful weapon in street fighting. A weakness was the army's lack of an anti-tank gun with real punching power.

The Great Losses

In 1941, the Red Army had some 5.37 million soldiers in the field, could call on another 5 million, and had 20,000 tanks (Dear, 963). Whilst impressive on paper, these figures belied many serious weaknesses. In the early months of the war, the Red Army suffered from poor organisation so that commanders were often located far from their troops, and front line units often lacked ammunition. Commanders rarely showed initiative (which had not been encouraged under Stalin's command system) and relied too heavily on infantry, even when facing armoured divisions. There was insufficient motor transport, optics were poor on many weapons, greatly affecting accuracy, and there was too great a dependency on vulnerable landlines rather than more secure and dependable radio communications.

Another problem was the use of Soviet tanks, Soviet commanders preferring to distribute them amongst infantry units and to use them solely as self-propelled artillery rather than weapons in their own right. Further, tanks were largely used in small groups, and this greatly reduced their effectiveness, especially when facing the massed tank divisions of the enemy.

The above deficiencies help to explain the Red Army's lacklustre performance in the Winter War of 1939-40, when Stalin attempted to invade Finland, and the first year of the German-Soviet War (1941-5) when Hitler's armies made great territorial gains from June 1941. The Axis armies employed Blitzkrieg ('lightning war') tactics, that is, a massive combination of fast-moving armoured and motorised infantry divisions with artillery and air support. Hitler's commanders frequently attacked on narrow fronts to push far into enemy territory and then encircle entire armies. Time and again, the Red Army could not find a response to these tactics. In just three bruising encounters, the Battle of Białystok-Minsk (Jun-Jul 1941), the Battle of Smolensk in 1941, and the Battle of Kiev in 1941, around 2 million Red Army soldiers were taken prisoner of war. Despite what they had been told by Nazi propaganda, though, the Axis soldiers soon realised their Soviet counterparts could be a force to be reckoned with when not let down by their superiors. One panzer group report of July 1941 noted:

The Russian fights tough and fiercely, attacks continually, is very skilled in defence…Resistance in the countryside constantly resurges. Often the Russian waits, well camouflaged and only when the distance is short does he open fire.

(Stahel, 221)

In all, during Barbarossa, the Red Army lost 4 million soldiers and 20,000 armoured vehicles (Zaloga, 5). The campaign did not achieve its aim of knocking out the Red Army, but it was certainly reeling from the huge losses in personnel and material. As in other armies, soldiers could write letters home. In one letter, written by Aleksandr Yegorov, the soldier reports the demise of his comrade Pavel Khlomyakov to Pavel's sister, Mariya:

Pavel's unit attacked on 16 September [1941]. Two enemy shells damaged his armour. His mechanic and gunner were killed and he was gravely wounded. He managed to get out of the tank and was lying on the grass for a long time. It was impossible to reach him under the fire, he was only given medical help in the evening. He was brought to a field hospital and this is all that I know…

(Dimbleby, 452).

The Great Victories

Eventually, the tide began to turn. Stalin rebranded the conflict the 'Great Patriotic War' and called for everyone to present a 'relentless struggle' that would make the USSR a fortress. The ruthless dictator also imposed a rigorous discipline in the Red Army after the defeats of the summer months. On 16 August 1941, he issued the following directive:

I order that: (1) anyone who removes his insignia during battle and surrenders should be regarded as a malicious deserter, whose family is to be arrested as the family of a breaker of the oath and betrayer of the Motherland. Such deserters are to be shot on the spot. (2) those falling into encirclement are to fight to the last and try to reach their own lines. And those who prefer to surrender are to be destroyed by any available means, while their families are to be deprived of all state allowances and assistance…This order is to be read to all companies, squadrons, batteries.

(Dear, 959)

Another method to ensure frontline troops fought as required was the formation of NKVD units, that is, units of the Soviet secret police who were stationed behind the regular troops ready to shoot deserters or those retreating without orders. These NKVD units eventually numbered around 10% of the total rifle infantry.

There was now a much better organisation between different division types, better tactics using armour, and the vital addition of specialised communications units. The Red Army began to improve considerably from 1943 onwards. Other improvements included the reduction in political deputies, an increase in artillery, and a greater distribution of machine guns and better tanks. The Red Army was also helped by the problems of logistics faced by the invaders, now deep in Soviet territory where few roads and partisan activities made getting fuel, ammunition, and supplies to the front ever more difficult. Winter weather caught the invaders unprepared as oil and lubricants in their vehicles froze. The Red Army, in contrast, was better equipped for a winter war and could be resupplied from factories which had already been moved to the safety of Central and Eastern Russia. Another help for Stalin's Red Army was an external one. Japan's attack on Pearl Harbour, the US naval base in the Pacific, on 7 December 1941, meant that the USSR would not now be threatened in the East and divisions there could be transferred to face the Axis forces in the West.

The USSR's losing streak was dramatically turned around at the Battle of Moscow (Oct 1941 to Jan 1942), which inflicted on Hitler his first great defeat of the war on land. Zhukov masterminded the counteroffensive in January 1942, which pushed back three Axis panzer armies and freed the capital from any future threat. As the Red Army advanced for the first time after a long series of retreats, the horrors of what the occupiers had perpetrated became clear. Homes had been razed to the ground, property of all kinds stolen, and civilians of all ages murdered. From then on, both sides would regularly commit atrocities as the war became ever more brutal.

More Soviet victories came with the successful defence at the Siege of Leningrad from September 1941 to January 1944. The Red Army, again thanks to Zhukov's meticulous planning, won the Battle of Stalingrad (July 1942 to February 1943), thereby destroying the Sixth Army, Hitler's largest, and capturing 91,000 Axis troops. The Red Army won the largest tank engagement in history, the Battle of Kursk (Jul-Aug 1943). Through 1944, the Axis invaders were steadily removed from Soviet territory. Finally, Berlin itself was occupied in April 1945, Hitler committed suicide, and Germany surrendered. Victory came at a great cost. Over 8 million Red Army soldiers died during WWII. Another 5.7 million Red Army soldiers were captured during the war, and 3.3 million of these died in captivity (Rees, 57).