Christopher Marlowe (1564-1593), also known as Kit Marlowe, was one of the most influential dramatists of Elizabethan theatre. Though he is best known for his plays, his poems were very popular in their time and are still well-regarded today. These include his translation of Ovid's Elegies, his pastoral poem A Passionate Shepherd to His Love, his narrative romance Hero and Leander, his epitaph On the Death of Sir Roger Manwood, as well as excerpts from his play Doctor Faustus.

Ovid's Elegies

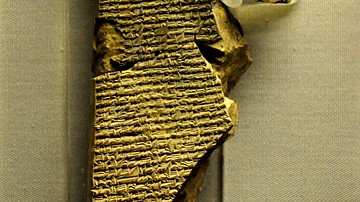

Scholars generally agree that Marlowe's earliest work was probably his translation of the Amores, three books of Roman literature by the poet Ovid (43 BCE to c. 17 CE) in which a male narrator addresses his mistress. The original poems, written in Latin when Ovid was still a young man, would have been viewed as rather scandalous in Marlowe's time; indeed, scholar Stanley Wells describes them as celebrating "the delights and excitements of, especially, illicit heterosexual love, of promiscuity, seduction, and adultery" (78). Marlowe's decision to translate this specific work, likely undertaken when he was still a student at Cambridge circa 1584, was therefore "a characteristically transgressive act" against "the religious and moral establishment" (ibid).

Marlowe's translation of the Amores – known in English as the Elegies – was a more groundbreaking work than it may first appear. Not only was it the first known translation of Ovid into English, but it was also the first time that the rhymed heroic couplet was used in such a long-form way in an English text. As scholar Georgia E. Brown explains, "the patterning and arrangement of words carries a lot of the argument in the couplet, which exploits balance and contrast, and lends itself to the process of comparison, juxtaposition, and apposition" (Cheney, 113). Marlowe was not merely translating an existing work, then, but building upon it, and creating something that English literature had not yet seen. One of the most famous poems from Marlowe's translation of Ovid's Elegies is the fifth elegy from Book One, in which the lust and passion of the narrator are on full display:

In summer's heat and mid-time of the day

To rest my limbs upon a bed I lay,

One window shut, the other open stood,

Which gave such light as twinkles in a wood,

Like twilight glimpse at setting of the sun

Or night being past, and yet not day begun.

Such light to shamefaced maidens must be shown,

Where they may sport, and seem to be unknown.

Then came Corinna in a long loose gown,

Her white neck hid with tresses hanging down:

Resembling fair Semiramis going to bed

Or Lais of a thousand wooers sped.

I snatched her gown, being thin, the harm was small,

Yet strived she to be covered therewithal.

And striving thus as one that would be cast,

Betrayed herself, and yielded at the last.

Stark naked as she stood before mine eye,

Not one wen in her body could I spy.

What arms and shoulders did I touch and see,

How apt her breasts were to be pressed by me?

How smooth a belly under her waist saw I?

How large a leg, and what a lusty thigh?

To leave the rest, all liked me passing well,

I clinged her naked body, down she fell,

Judge you the rest: being tired she bade me kiss,

Jove, send me more such afternoons as this.

The Passionate Shepherd

This pastoral poem, initially untitled, was first published posthumously in 1599. When it was printed, it was given the full title The Passionate Shepherd to His Love, thereby fixing the gender of the speaker as male; if one were to look only at the text, however, there is nothing to indicate the gender of either the narrator or the addressee. The speaker, according to scholar Georgia E. Brown, is "a compound of dominance and suppliance" whose request for companionship is also "open to erotic reconstruction" (Cheney, 114). The lack of response from the addressee leaves the poem's ending open to interpretation – the silence could mean that the shepherd's love has submitted to his entreaty, but it could also mean that she has spurned him. One of the most famous Elizabethan lyrics, the poem offers an idealized vision of country life, with the speaker promising to make for his love a life so blissful and romantic as to be practically fanciful. Sir Walter Raleigh (c. 1553-1618) points this out in his famous response to the poem entitled The Nymph's Reply to the Shepherd (1600), in which he reminds Marlowe's shepherd that time erases all things, and that the pastoral paradise he offers his love will not last. The poem, which remains among Marlowe's best-known works, is fully quoted here:

Come live with me and be my love,

And we will all the pleasures prove

That valleys, groves, hills, and fields,

Woods, or steepy mountain yields.

And we will sit upon the rocks,Seeing the shepherds feed their flocks,

By shallow rivers to whose falls

Melodious birds sing madrigals.

And I will make thee beds of rosesAnd a thousand fragrant posies,

A cap of flowers, and a kirtle

Embroidered all with leaves of myrtle.

A gown made of the finest woolWhich from our pretty lambs we pull;

Fair lined slippers for the cold,

With buckles of the purest gold;

A belt of straw and ivy buds,With coral clasps and amber studs;

And if these pleasures may thee move,

Come live with me, and be my love.

The shepherd swains shall dance and singFor thy delight each May morning:

If these delights thy mind may move,

Then live with me and be my love.

Hero and Leander

Hero and Leander is often judged as Marlowe's masterpiece. A narrative poem written in two sestiads (i.e., a work of poetry divided into six parts), Hero and Leander retells a story from ancient Greek mythology about two young lovers living in cities on opposite sides of the Hellespont; Hero, a beautiful priestess of Venus, lives in Sestos on the European side of the strait, while Leander is an attractive young man living in Abydos on the opposite side. In the first sestiad, Hero and Leander meet at a festival honoring Venus and fall in love at first sight:

The men of wealthy Sestos every year,

For his sake whom their goddess held so dear,

Rose-cheek'd Adonis, kept a solemn feast.

Thither resorted many a wandering guest

To meet their loves; such as had none at all

Came lovers home from this great festival…

But far above the loveliest, Hero shin'd,

And stole away th' enchanted gazer's mind;

For like sea-nymphs inveigling harmony,

So was her beauty like to the standers-by'

Nor that night-wandering, pale, and watery star

(When yawning dragons draw her thrilling car

From Latmus' mount up to the gloomy sky,

Where, crown'd with blazing light and majesty,

She proudly sits) more over-rules the flood

Than she the hearts of those that near her stood…

On this feast-day – O cursed day and hour! –

Went Hero thorough Sestos, from her tower

To Venus' temple, where unhappily,

As after chanc'd, they did each other spy…

And in the midst a silver altar stood:

There Hero, sacrificing turtles' blood,

Vail'd to the ground, veiling her eyelids close;

And modestly they opened as she rose.

Thence flew Love's arrow with the golden head;

And thus Leander was enamoured.

Stone-still he stood, and evermore he gazed,

Till with the fire that from his count'nance blazed

Relenting Hero's gentle heart was strook:

Such force and virtue hath an amorous look.

It lies not in our power to love or hate,

For will in us is over-rul'd by fate.

When two are stript, long ere the course begin,

We wish that one should lose, the other win;

And one especially do we affect

Of two gold ingots, like in each respect:

The reason no man knows, let it suffice,

What we behold is censur'd by our eyes.

Where both deliberate, the love is slight:

Who ever lov'd, that lov'd not at first sight?

After they fall in love, Leander promises Hero that he will swim across the Hellespont each night to be with her – he asks her to light a lamp in the window of her tower every night so that he can find his way to her. On the first night, Leander is spotted by the god Neptune who becomes enraptured by his beauty and drags him to the bottom of the ocean. But before the youth can drown, the sea god returns him to shore with a bracelet that is supposed to keep him from drowning. He knocks on Hero's door and the poem ends after they have spent the night together, just as dawn is about to break. The second sestiad ends at this moment of bliss:

Even as a bird, which in our hands we wring,

Forth plungeth, and oft flutters with her wing,

She trembling strove; this strife of hers, like that

Which made the world, another world begat

Of unknown joy. Treason was in her thought,

And cunningly to yield herself she sought.

Seeming not won, yet won she was at length;

In such wars women use but half their strength.

Leander now, like Theban Hercules,

Entered the orchard of th'Hesperides;

Whose fruit none rightly can describe, but he

That pulls or shakes it from the golden tree.

Wherein Leander on her quivering breast,

Breathless spoke something, and sighted out the rest;

Which so prevailed, as he, with small ado,

Enclosed her in his arms and kissed her too;

And every kiss to her was as a charm,

And to Leander as a fresh alarm:

So that the truce was broke, and she, alas,

Poor silly maiden, at his mercy was!

Love is not full of pity, as men say,

But deaf and cruel where he means to prey.

And now she wished this night were never done,

And sighed to think upon th' approaching sun;

For much it grieved her that the bright day-light

Should know the pleasure of this blessed night,

And them, like Mars and Ericyne, display,

Both in each other's arms chained as they lay.

Again, she knew not how to frame her look,

Or speak to him, who in a moment took

That which so long, so charily she kept;

And fain by stealth away she would have crept,

And to some corner secretly have gone,

Leaving Leander in the bed alone.But as her naked feet were whipping out,

He on the sudden clinged her so about,

That mermaid-like, unto the floor she slid;

One half appeared, the other half was hid.

Thus near the bed she blushing stood upright,

And from her countenance behold ye might

A kind of twilight break, which through the hair

As from an orient cloud, glimpsed here and there;

And round about the chamber this false morn

Brought forth the day before the day was born.

So Hero's ruddy cheek Hero betrayed,

And her all naked to his sight displayed:

Whence his admiring eyes more pleasure took

Than Dis, on heaps of gold fixing his look.

By this, Apollo's golden harp began

To sound forth music to ocean;

Which watchful Hesperus no sooner heard,

But he the bright Day-bearing car prepared,

And ran before, as harbinger of light,

And with his flaring beams mocked ugly Night,

Til she, o'ercome with anguish, shame, and rage,

Danged down to hell her loathsome carriage.

Although Marlowe's poem ends here, the original Greek story has a more tragic ending – Leander drowns during one of his nightly swims and Hero, unable to live without her love, jumps from her tower to her death. It is unknown, therefore, whether Marlowe's poem was uncompleted; perhaps he had meant to finish the narrative but met his own untimely death before he was able to. Or perhaps Marlowe intended to end the story here on the happier note of romantic bliss rather than follow the original tale through to its bitter end. In either case, Hero and Leander proved immensely popular in its day and was often read alongside William Shakespeare's similar poem Venus and Adonis, which many scholars believe was heavily influenced by Marlowe's work.

On the Death of Sir Roger Manwood

One of Marlowe's least-read poems is his elegy for Sir Roger Manwood, a Kentish judge and member of Parliament for Marlowe's hometown of Canterbury. The poem was written in late 1592, shortly after Manwood's death, and is conspicuous for being Marlowe's only known work to praise a public figure. Why Marlowe decided to write an epitaph for Manwood specifically is unknown. Perhaps Manwood had aided him financially while he was a student at Cambridge, and this was his way of giving thanks. Or perhaps Marlowe was seeking patronage at the end of 1592 and hoped that, by eulogizing a famous figure from Kent, he might find a willing patron there. In any case, On the Death of Sir Roger Manwood is likely one of the last poems Marlowe ever wrote, as he was killed just a few months later in May 1593. Originally written in Latin, the epitaph praises the virtue of Manwood as a judge, and laments how joyful wicked criminals must be to no longer have to worry about him:

The terror of him who prowls by night, the stern scourge of one

who is profligate, both a Hercules, son of Jove, and a bird of prey

upon the rough brigand, is encased in an urn. Rejoice, ye sons of

wickedness; mourn, unoffending one, with hair in disorder over

your pitiable neck. The light of officialdom, the glory of the wor-

shipful law, lies dead. Alas, much virtue has passed with him to the

barren shores of Acheron. In view of his so numerous virtues, spare,

O Envy, this one man; be not overly presumptuous toward the

ashes of one whose glance has held thunderstruck so many thousands

of mortals. On these terms, when Death's pale messenger wounds

you, may your bones rest happily, and may your fame survive the

memorials of your marble tomb.

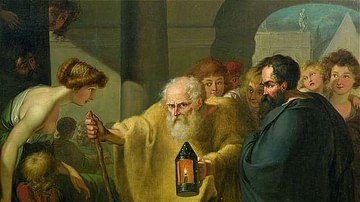

Excerpts from Doctor Faustus

Although the following excerpts are not poems but part of a larger play, it would be remiss to exclude them from this article, as they constitute some of the most famous – and moving – passages by Marlowe. The play Doctor Faustus centers around a scholar who sells his soul to Lucifer in exchange for magical powers. At first, Faustus enjoys his powers as he conjures up the spirit of Helen of Troy. The monologue he speaks to her, anticipating the amorous lines of Shakespeare, exemplifies why Doctor Faustus remains one of Marlowe's most oft-performed plays today:

Was this the face that launch'd a thousand ships,

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss.

Her lips suck forth my soul: see where it flies!

Come, Helen, give me my soul again.

Here will I dwell, for heaven is in these lips,

And all is dross that is not Helena...

O, thou art fairer than the evening air

Clad in the beauty of a thousand stars…

(Faustus 5.1.90-104).

Eventually, however, Faustus realizes the folly of his bargain when the time comes for the Devil to take his soul. The passage in which Faustus laments that he must take his leave of earth is, according to Stanley Wells, "an extraordinary speech to have been written by a self-proclaimed atheist, showing that Marlowe, whatever his personal beliefs, had the imaginative power to project a profoundly religious state of mind" (92). Indeed, the speech demonstrates the timeless fear of damnation and desperate hope for salvation that many people, religious or otherwise, have grappled with:

Ah Faustus,

Now hast thou but one bare hour to live,

And then thou must be damned perpetually.

Stand still, you ever-moving spheres of heaven,

That time may cease and midnight never come!...

The stars move still; time runs; the clock will strike;

The devil will come, and Faustus must be damned.

O, I'll leap up to my God! Who pulls me down?

See, see where Christ's blood streams in the firmament!

One drop would save my soul, half a drop. Ah, my Christ!

Ah, rend not my heart for naming of my Christ!

Yet will I call on him.

(Faustus 5.2.57-73).