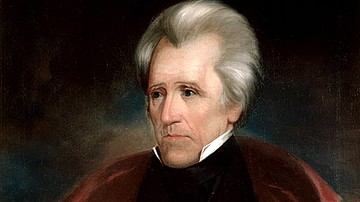

The Battle of New Orleans (8 January 1815) was the final major battle of the War of 1812, in which a ragtag American army under Major General Andrew Jackson (1767-1845) beat back a superior British force under Major General Sir Edward Pakenham (1778-1815). The battle was incredibly lopsided – the Americans suffered 71 casualties while the British suffered over 2,000 – and was fought after the peace had been signed. But despite its needlessness, the battle gave the fledgling United States a new self-confidence in its sovereignty and set its victor, Jackson, on the path to the presidency.

Pakenham & the British Invasion

The events that would lead to the bloodshed at New Orleans were set into motion three months before when, on a cool October evening, Sir Edward Pakenham received a letter from Lord Bathurst, Secretary of State for War and the Colonies. It informed him that the Prince Regent had been "pleased to confer upon you the Command of all the Troops operating with His Majesty's Fleets upon the Coasts of the United States" and directed him to conduct operations against New Orleans, a city strategically situated at the mouth of the Mississippi River (quoted in Napoleon Series). Bathurst hoped that by striking this vulnerable underbelly, the British could draw American attention away from Canada, where most of the fighting had been taking place; if the British could then push into the lands of the Louisiana Purchase to use as a bargaining chip for peace negotiations, all the better. Indeed, American and British diplomats were currently negotiating peace at Ghent in the United Netherlands (modern Belgium). However, Bathurst told Pakenham to disregard any rumors of peace he may hear and proceed with the campaign no matter what.

A dutiful and ambitious man, Pakenham threw himself into preparations for the campaign. Since the age of 16, when his family had bought him a lieutenant's commission in the British Army, Pakenham had known nothing but a soldier's life. He had most recently fought against the armies of Napoleonic France in the Peninsular War (1808-1814), serving under the command of his famous brother-in-law, Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1769-1852). Pakenham had distinguished himself at the Battle of Salamanca (22 July 1812), where he led his 3rd Division in a bayonet charge that drove the French soldiers back in a state of 'irremediable confusion'. For such actions, he had been knighted and promoted to the rank of major general. Having spent years fighting Napoleon's veteran soldiers, Pakenham felt he had no reason to worry about the backcountry militias of Louisiana and Tennessee. In November, Pakenham set out from London to join his army, which was already en route to New Orleans – having assembled in Jamaica, the British troops had boarded 50 Royal Navy ships under Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane and sailed into the Gulf of Mexico, anchoring just east of Lake Borgne, Louisiana, on 14 December 1814.

Access to Lake Borgne was blocked by five American gunboats under Lt. Thomas ap Catesby Jones. In the evening, 980 British sailors and Royal Marines got into 42 rowboats and silently rowed out to dislodge Jones' small force. After a brief engagement, the British succeeded in capturing the gunboats at the cost of 17 dead and 77 wounded (the Americans lost 6 dead and 35 wounded). The British then began to disembark; over the next six days, 1,600 soldiers under Maj. Gen. John Keane rowed out to Pea Island, about 30 miles (48 km) east of the city. They advanced overland until, on the morning of 23 December, they reached the east bank of the Mississippi River, 9 miles (14 km) south of New Orleans. Keane stopped there to await reinforcements. As his soldiers set up camp, some of them broke into the home of Major Gabriel Villeré, who leapt out a window and ran all the way to the American lines outside New Orleans. The soldiers he found there were a ragged hodgepodge of 4,000 men: French-speaking Louisiana militia and crude-talking Tennessee frontiersmen, mounted Mississippi dragoons, and undersupplied Irish immigrants, two battalions of Black men, some enslaved and some free, as well as Choctaw Indians, pirates, and privateers. But perhaps the most striking figure of them all was their commander, a tall, thin frontiersman with piercing blue eyes and a fiery temper named Andrew Jackson.

Jackson Arrives in New Orleans

Jackson was a passionate man with a capacity for deep loathing, and there were few people he loathed more than the British. In 1781, when the American Revolutionary War (1775-1783) had reached his home state of South Carolina, the teenaged Jackson and his brother Robert were taken captive by British soldiers. When Jackson refused to shine a British officer's boots, he was punished by a slash of the officer's sword, leaving scars on his left hand and head that he would carry for the rest of his life. He and his brother were then sent to languish in a prisoner-of-war camp, where they became malnourished and contracted smallpox. They were ultimately released in a prisoner exchange, though Robert would never recover, dying two days after coming home. Their mother, too, died shortly afterward, leaving Jackson alone in the world at the age of 14 – he blamed the British for the destruction of his family, and nothing would make him forget it.

At the onset of the War of 1812, Jackson raised an army of 2,000 volunteers from his adopted state of Tennessee and marched them to the defense of New Orleans – noted for his toughness, the 45-year-old Jackson was nicknamed 'Old Hickory' by his men. By 1813, he was waging war against the 'Red Sticks', a faction of Muscogee (Creek) Native Americans supported by the British. He won blood-drenched victories at Tallushatchee (3 Nov 1813) and Horseshoe Bend (27 March 1814), after which he forced the Creeks to cede vast tracts of territory in modern Alabama and Georgia to the United States. Then, he took the war into Spanish Florida, defeating Spanish and British troops at the Battle of Pensacola (7-9 Nov 1814). He was still at Pensacola when word reached him that the British were planning an attack on New Orleans. Aware that the city was the key to the American West, Jackson rushed to its defense, taking all the state militia and regular troops at his disposal.

He arrived on 1 December 1814; by mid-month, having learned of Admiral Cochrane's fleet off Lake Borgne, he decided to impose martial law. Before long, he had accumulated 4,000 men, including aristocrats, Choctaw Indians, and slaves, and had struck an alliance with a band of pirates and smugglers under Jean Laffitte (circa 1780-1823) and his brother Pierre. Jackson was quick to put these men to work, constructing three lines of defense outside the city – the outer line, dubbed 'Line Jackson', had been constructed along the Rodriguez Canal, which served as a sort of defensive moat, and was anchored by a large swamp on one end and stretched all the way to the bank of the Mississippi on the other. Cannons were placed in redoubts at important intervals, protected by logs, earth, and cotton bales smeared with mud. But not everyone supported Jackson's implementation of martial law – Louis Louaillier, a member of the Louisiana legislature, wrote a letter denouncing it. Jackson did not deign to defend himself with words; instead, he simply had Louaillier arrested. When US District Court Judge Dominic A. Hall signed a writ of habeas corpus for Louaillier's release, Jackson not only ignored it but had the judge arrested, too. Clearly, Old Hickory was not the sort of man to let the rule of law get in between him and his goals.

Skirmishes

And so, after Villeré told Jackson all he knew of the British encampment, the general found himself itching for a fight. On the night of 23 December, Jackson quietly led 2,131 men against Keane's unsuspecting British troops. Launching a three-pronged attack, the Americans caught the British completely by surprise and drove them from their camp. After this brief skirmish, Jackson pulled his troops back to 'Line Jackson'; he had lost 24 killed, 115 wounded, and 74 missing but had inflicted 46 dead, 167 wounded, and 64 missing on the British. The next day – Christmas Eve – Pakenham finally arrived to personally take command of the British army; that same day, unbeknownst to any of the combatants, the Treaty of Ghent was signed in Europe, bringing the war to an end. It would take weeks for this news to cross the Atlantic, by which time it would be much too late for many of the doomed men now gearing up for battle beneath the shadow of New Orleans.

Pakenham spent the next few days securing his position. On 26 December, he brought up nine naval artillery guns taken off Cochrane's frigates and directed them at the two US Navy warships that had been harassing the British from the river – the schooner USS Carolina was sunk, going up in a fiery explosion, while the USS Louisiana was damaged beyond the point of posing a threat. Two days later, Pakenham ordered a large-scale assault to probe the American earthworks and test for weaknesses – Pakenham's second-in-command, Maj. Gen. Samuel Gibbs, commanded the right column of the offensive, while Gen. Keane commanded the left. Gibbs' men succeeded in pushing back Jackson's picket line and got within a few yards of 'Line Jackson' itself. Keane's men fared less well, shredded by the enfilading fire from the grounded USS Louisiana on the riverbank. Seeing the damage that Keane's troops were taking, Pakenham decided to call off the entire assault, even though Gibbs' men were making progress; had he pressed on, the campaign may have turned out quite differently.

The near success of Gibbs' assault convinced Jackson there were weaknesses in his line, and he once again set his men to digging and re-entrenching their position. On 1 January 1815, Pakenham's army had moved into position, and the British celebrated the New Year by opening an artillery bombardment on the American line. Jackson, who was having breakfast when the barrage began, barely escaped his headquarters building before it was demolished by enemy fire. Gradually, the American cannons roared to life, beginning a three-hour artillery duel; by the time it was over, the British guns had suffered more damage than they inflicted. Pakenham, who had hoped to follow a successful bombardment with an infantry assault, decided to call off the attack to wait for more men and ammunition. He had to wait as his men ferried the supplies all the way from Cochrane's ships, affording Jackson another opportunity to strengthen his line. On 4 January, Jackson was reinforced by Kentucky militiamen, boosting his numbers to about 5,700. Only a few hundred of them were armed, however, leading Jackson to unhappily jest that this was the first time he had ever seen a Kentuckian "without a gun, a pack of cards, and a jug of whiskey" (quoted in Howe, 11). He armed them with spare weapons from the arsenal kept by the city in case of slave revolts and sat down to await the attack he knew was coming.

The Battle: 8 January 1815

On 7 January, Pakenham was finally reinforced by 2,000 more troops under Maj. Gen. John Lambert – bringing his total number to about 8,000 – and he decided to attack the next morning. His plan called for a substantial number of troops under Col. William Thornton to cross the Mississippi in the dead of night, storm the American battery on the east riverbank, and turn those guns against Jackson's lines. Gibbs would simultaneously lead 2,500 men in the main assault against Jackson's center while Keane would conduct a feint toward the river with 1,200 troops to attract the fire of the heavy American guns. Lt. Col. Timothy Jones would lead a detachment of light infantry through the swamps on the American left flank, while Lambert's newcomers would be kept in reserve. To get over Jackson's earthworks, the British soldiers were to be equipped with ladders and fascines (bundles of sugarcane used to fill the ditch).

At dawn on Sunday, 8 January, Pakenham was informed that Thornton's troops had had difficulty crossing the Mississippi and were not yet in place, while some assault troops had been unable to locate their ladders or fascines; the responsibility of placing the scaling equipment had been that of Lt. Col. Thomas Mullins, who had failed to do so in time. But rather than postpone the attack until everything was in place, Pakenham decided he could wait no longer – with a shrill whistle, a flaming Congreve rocket carved a parabola into the dark sky, the signal for the attack to commence. With mechanical discipline, the red-coated British troops advanced into the early morning fog and onto the field known as Chalmette plantation. The leading elements of Keane's column – led by Lt. Col. Robert Rennie – were slightly ahead of the rest of the British troops. They advanced along the west bank of the riverside, driving back the American pickets. Presently, they emerged from the fog, right into the line of sight of Jackson's artillery.

The earth shook as the American cannons spewed fire, smoke, and lead into the oncoming line of British soldiers. Riddled with grapeshot, scores of men crumpled to the ground, a jumbled mess of blood and mangled limbs. Yet Rennie pushed onward and, before long, his men had overrun an American redoubt beside the river. Bleeding from a wound, Rennie attempted to hold this position as he awaited the rest of Keane's column. In the meantime, Gibbs' men were advancing against the left center of Jackson's line, when they also came under heavy fire from the American artillery. Bogged down by several water-filled drainage ditches, Gibbs' troops had little choice but to press themselves to the ground, praying that the American cannonballs would soar harmlessly above their heads. Slowly, they advanced within 100 yards (91 m) of the American line, when the air filled with the crackle of musket fire. Lacking enough ladders or fascines to storm the American position, Gibbs' men were left with little recourse but to dive into the canal or seek shelter in one of the ditches. His line began to waver.

Pakenham, noticing that Gibbs' attack was in danger, rode out to give encouragement. He rode too close to the enemy lines, however, and his horse was shot out from under him – as he was mounting another, he was hit by a round of grapeshot and fell, mortally wounded. Gibbs did not long outlast him, falling dead about 20 yards from the American line. Wave after wave of grapeshot from the American cannons tore through cloth and flesh and muscle, while Tennessee and Kentucky riflemen took shots at the terrified British soldiers, huddling in the ditch. Keane, whose main body was still advancing in support of Rennie, noticed that Gibbs' column was melting away and dispatched the 93rd Highlanders under Lt. Col. Robert Dale to bolster them. The Highlanders were quickly torn apart, and before long, Dale lay dead alongside the bleeding corpses of his countrymen. Keane himself was wounded in the neck and carried off the battlefield – his wound was not mortal, but in the captured American redoubt, Rennie was dead, along with most of his men. On the left flank, Col. Jones' light infantrymen had also been repulsed, and Jones, too, had fallen mortally wounded. There were some British successes; on the other side of the river, Col. Thornton had managed to drive back the Kentucky militia and capture the artillery, as ordered. But he was too late – the main assault had failed. As the sun continued to climb into a bitter January sky, it shone out over a wet field littered with the dead and the dying.

Aftermath

The Battle of New Orleans was over in a little more than two hours. The British assault had been repulsed, and the defeat came at a horrendous cost – 291 killed, 1,262 wounded, and 484 missing. The Americans, by contrast, had lost only 13 killed, 39 wounded, and 19 missing or captured. This incredibly lopsided victory would draw comparisons to the Battle of Agincourt (25 October 1415) in which the hapless French knights, bogged down by mud, were mowed down by the English longbowmen; now it had been the British who had gallantly but needlessly thrown their lives away before the American cannons and rifles. In the aftermath of the battle, Gen. Lambert took command of the British army. Rather than abandon the campaign, he led his men back to the ships and sailed them up the Mississippi, bombarding Fort St. Philip for nine days – Jackson, having achieved his objective of saving the city, did not pursue. It hardly mattered, for news soon reached the soldiers that the war had been over for about a month. The Battle of New Orleans need not have been fought at all.

Needless though it may have been, the battle had a major psychological impact on the American people. The Treaty of Ghent had restored both nations to their prewar borders, meaning that the War of 1812 had ended in a sort of draw – New Orleans left the Americans feeling as though they had gotten the final word, satisfying their national honor. As a result, it strengthened their self-confidence as a nation and helped usher in the next decade of political stability known as the 'Era of Good Feelings'. As for Jackson himself, the battle turned him into a national hero and would set him on the path to the presidency 14 years later.