The Battle of Zama (202 BCE) was the final engagement of the Second Punic War (218-202 BCE) at which Hannibal Barca of Carthage (l. 247-183 BCE) was defeated by Scipio Africanus of Rome (l. 236-183 BCE) ending the conflict in Rome's favor. The Second Punic War had begun when Hannibal attacked the city of Saguntum, a Roman ally, in Spain and continued with a number of stunning victories by Hannibal in Italy, most notably the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE.

Hannibal seemed unstoppable until Scipio took command of the Roman forces after Cannae, defeated Hannibal's brother Hasdrubal Barca (l. c. 244-207 BCE) in Spain, driving him into Italy, and then drawing Hannibal back to North Africa by threatening the city of Carthage. Hannibal met Scipio at Zama in defense of his home city but Scipio, using Hannibal's same tactics from Cannae, won the day and Carthage fell to the Romans.

Hannibal then lived the rest of his life as a fugitive, finally taking his own life rather than ever surrender to the Romans. Although initially hailed as Rome's savior, Scipio was later vilified by his countrymen who forgot what they owed him. He left Rome for his villa and gave instructions in his will that he should be buried at his estate rather than in the ungrateful city of Rome. The Battle of Zama is remembered for Scipio's brilliant tactics, based on Hannibal's, which would afterwards become standard operating procedures for the Roman military and enable them to build their empire.

Background & First Punic War

Carthage and Rome first came into conflict over the island of Sicily, which both controlled parts of, igniting the First Punic War (264-241 BCE). The Carthaginian forces were led by Hamilcar Barca (l. 275-228 BCE) who used his fleet to strike without warning at Roman ports and outposts along Italy's coast, cutting supply lines, and then attacking with his army. Carthage, at the beginning of the war, had the greatest fleet in the Mediterranean while the Romans were only used to land engagements. Hamilcar's clever tactics and his crews' experience in Carthaginian naval warfare led to a series of decisive victories early in the war.

Rome quickly taught itself how to fight at sea, however, and the Carthaginian government offered their general little support so the tide of the war shifted in favor of the Romans. Hamilcar defeated Rome at Drepana in 249 BCE but, receiving less and less support from his home government, steadily lost engagements while Rome grew stronger until, in 241 BCE, Carthage was forced to sue for peace and had to pay a large war indemnity to the victors.

Afterwards, Hamilcar went to the Carthaginian-held regions of Spain – ostensibly to take control of the silver mines there to pay Carthage's debt to Rome – and began reequipping the Carthaginian army to resume the war. He brought his son Hannibal with him as well as his son-in-law Hasdrubal the Fair (l. c. 270-221 BCE) and, later, his younger son Hasdrubal Barca.

When Hamilcar died in 228 BCE, command of the army went to Hasdrubal the Fair who favored diplomatic measures with Rome over military conflict. Hasdrubal the Fair negotiated the Ebro Treaty in 226 BCE which stipulated that Roman and Carthaginian territories in Spain would be set by the Ebro River: Rome would hold the regions to the north, Carthage the regions to the south, and neither would infringe upon the others' lands. Hasdrubal the Fair was assassinated in 221 BCE, however, and command went to Hannibal, who had sworn eternal enmity with Rome.

Second Punic War & Cannae

In 218 BCE, the Romans initiated a coup in the city of Saguntum, which was south of the Ebro, and installed a government hostile to Carthage. Hannibal marched on the city, lay siege and took it, which the Romans claimed was an act of war. They demanded Hannibal be turned over to them and, when the Carthaginian senate refused, war was declared.

Hannibal left his brother Hasdrubal in charge of the troops in Spain and marched his army over the Alps into Italy to bring the fight to the Romans. He defeated every Roman force sent against him, culminating in the Battle of Cannae in 216 BCE where he lured the Romans into a trap. Knowing the Romans favored their traditional tactic of masking their heavy infantry behind the front line of their lighter infantry with cavalry support from the wings, Hannibal formed a crescent formation with his light infantry at the center and his heavy infantry in a crescent formation.

The Romans relied on the strength of the charge to break the center of an enemy's lines through sheer strength of numbers and so, in this battle, drove toward the center of Hannibal's lines which gave way before them. The Romans, encouraged, drove on but the Carthaginians who seemed to be retreating were actually reforming to the left and right along the crescent. There was, therefore, no longer an actual center for the Romans to break – although it seemed there was – and by the time they realized their mistake, they were surrounded and the trap was closed. Out of the over 80,000 Romans troops on the field, 44,000 were killed and the rest scattered.

Rome was completely demoralized and could find no general to step up and take command of what was left of the Roman army as every general now seemed to feel that facing Hannibal in battle was a suicide mission. Scipio volunteered, though he was only 24 years old at the time and considered too young and inexperienced to stand a chance against Hannibal. He left for Spain with 10,000 infantry and 1,000 cavalry to engage Hasdrubal Barca who had killed both his father and uncle at the Battle of Upper Baetis in 211 BCE.

Scipio in Spain

Scipio led his troops against the city of Carthago Nova (New Carthage) in Spain in 209 BCE. New Carthage was thought to be impregnable owing to its fortifications and the natural defense of a lagoon protecting one whole side of the city. Prior to Cannae, Roman warfare relied largely on strength of numbers and sheer might of force in taking a city or driving an enemy from the field. Scipio, following Hannibal's lead of a thinking commander, gathered intelligence that the water level of the lagoon could be dropped to a considerably lower level through sluices which allowed water in and out of the lagoon. The lagoon was used as a salt marsh for harvesting salt from the sea and Scipio realized all he had to do was distract the city's defenders long enough to lower the lagoon's level enough to allow for a crossing of his infantry.

Directing his second-in-command, Gaius Laelius, to mount a naval attack, and sending his infantry against the gates of the city, Scipio seized on this advantage of the lagoon. He led a column through the water at low tide – after the sluices had been utilized – breached the walls, and captured the city. Scipio would continue on with this same type of strategy in his other engagements with the Carthaginian forces.

In 208 BCE, Scipio met Hasdrubal Barca in battle at Baecula and recognized that, in order to attack, he would have to send his troops across a small river to then charge uphill against a fortified position. Again considering what Hannibal might do in such a situation, Scipio noted the dried gulleys on either side of the plateau Hasdrubal had fortified and so sent a lightly armed force straight ahead across the river and up the slope while his main force divided and drove toward the two gulleys. The Carthaginians were focused on the center, moved to engage, and were crushed by the wings which struck from either side.

Hasdrubal retreated with what was left of his army and followed Hannibal's course over the Alps and into Italy. Before he could join his army with Hannibal's, however, he was defeated by Gaius Claudius Nero (l. c. 237 - c. 199 BCE) at the Battle of the Metaurus where he was killed. Nero then returned to trying to trap and destroy Hannibal – which he had been unable to do definitively thus far – while Scipio finished up his work in Spain.

Battle of Zama

Scipio recognized that if he struck at Carthage itself Hannibal would be recalled from Italy to defend it and so withdrew from Spain and invaded North Africa in 205 BCE. After a siege, he took the city of Utica, allied himself with the Numidian King Masinissa, and marched on Carthage. Hannibal, who had been devastating Italy for the past twelve years, was recalled to defend the city. Scholar Ernle Bradford describes how the field of battle was chosen:

Hannibal marched west in the direction of a town called Zama, which is probably to be identified with a later Roman colony Zama Regia (Jama) ninety miles west of Hadrumetum. Reports had reached him that Scipio was engaged in burning villages, destroying crops, and enslaving the inhabitants of all this fertile area, upon which Carthage depended for its grain and other food. It can only have been this driving necessity which that made Hannibal march after Scipio, for on the surface it seems more logical for him to have taken his army in the direction of Carthage and interposed himself between Scipio and the city. But the latter's systematic destruction of towns and villages, and his present activities in the Carthaginian hinterland, clearly precluded the ability of the city to feed a further 40,000 or so men, together with their horses and elephants, as well as its own teeming masses. The main cause, then, for the battle taking place where it did arouse out of a matter of supplies to the capital. Scipio knew what he was doing, and had quite deliberately drawn Hannibal away from the city so as to decide the outcome of the war in an area selected by himself. (196-197)

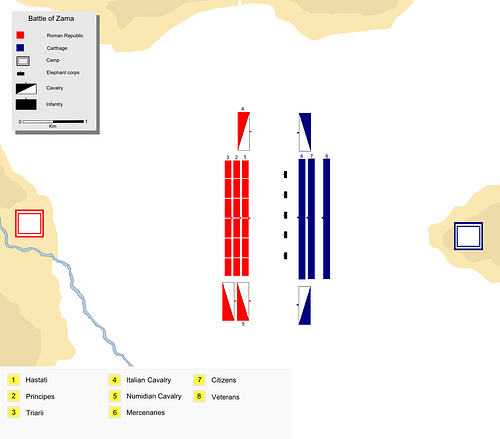

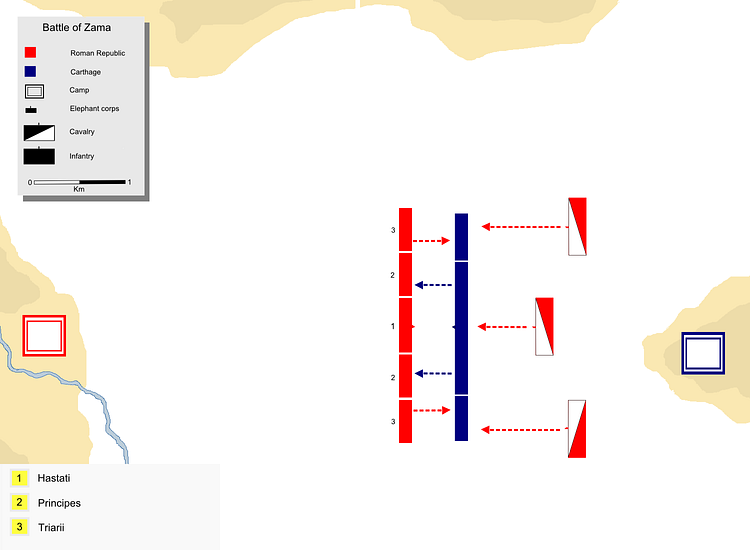

Both armies numbered about 40,000 when they met on the field. In Italy, Hannibal had been forced to fight without elephants (most of whom had been lost in his crossing of the Alps), but now back in Africa he arranged his elephant corps at the front of his lines followed by a continuous line of mercenaries, then Libyan allies, and finally his Carthaginian veterans from the Italian campaigns. To his left and right, he set his cavalry in the wings.

Scipio also arranged his lines but, instead of a continuous, unbroken line across the field, set the soldiers in columns. The gaps in these columns were masked by light infantry toward the front, making it appear as though Scipio had formed his men in the same way as Hannibal had his. To the Roman army's left wing were the Italian cavalry, commanded by Gaius Laelius, and, to the right, the Numidian cavalry of Masinissa.

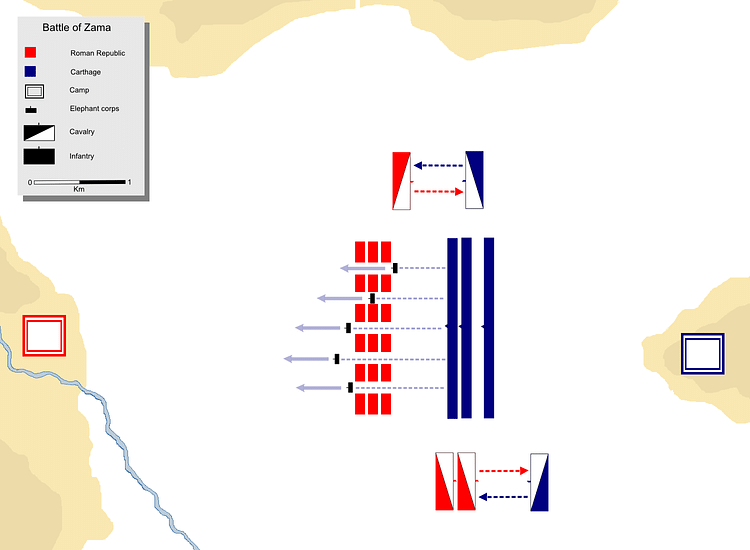

Hannibal made the first move, sending his elephants charging toward Scipio's forces. Scipio ordered his men to hold their positions and then, at a given signal, the light infantry masking the front line moved into the columns and, at the same time, Scipio ordered his trumpets to blow and drums beat. The elephants ran harmlessly through the alleys between the columns or, startled by the trumpet blasts and the loud shouts of the Romans, turned around to trample the Carthaginian forces. Hannibal's elephant charge had failed.

The Roman and Numidian cavalry then deployed and attacked the Carthaginian cavalry, driving them from the field. In doing so, the Roman cavalry swung to the left and right around the infantry forces on the field and the two cavalry forces fought behind the Carthaginian lines. Scipio's infantry now advanced, mobilizing from the column formation to continuous lines, and pushed back the mercenary front lines of the Carthaginians.

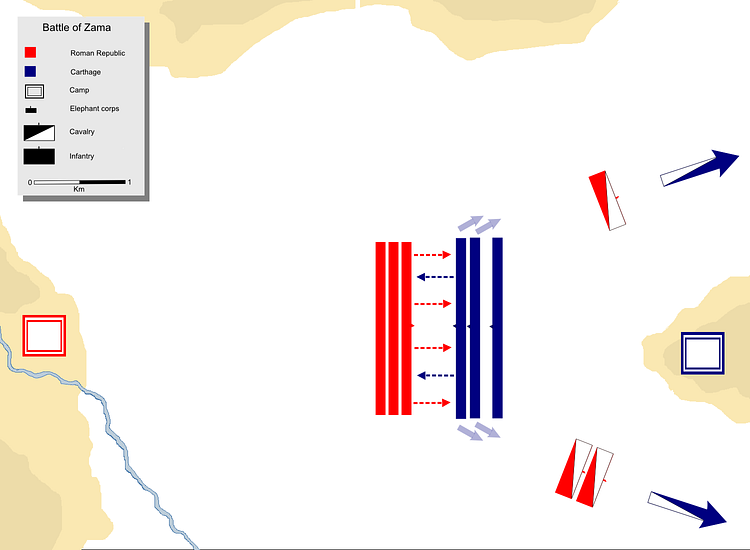

The lines were so densely packed that the mercenaries fell back into the Libyan forces who could not give way because of the Carthaginians behind them. As the mercenaries were being crushed between the advancing Roman forces and the Libyans, they began to attack the Libyans to break through and escape. At this same time, the combined cavalry of Laelius and Masinissa returned to fall on the Carthaginian forces in the rear.

Hannibal's forces were all but surrounded; 20,000 were killed and many more severely wounded. Hannibal himself escaped back to Carthage where he told the senate that he lost not only the battle, but the war, and suggested they sue for peace.

Conclusion

The two generals met after the battle to discuss terms and Scipio pardoned Hannibal who then became chief magistrate of Carthage. Rome again imposed a heavy war indemnity which was paid owing to Hannibal's skill and dedication to his new position, but the Carthaginians blamed him for losing the war and denounced him to Rome, claiming he was attempting to make Carthage powerful enough to challenge the Romans in a new war. Hannibal recognized he would probably be handed over to Rome and fled for Tyre, then to the court of Antiochus III (the Great, r. 223-187 BCE) of the Seleucid Empire, and finally to the court of King Prusias of Bithynia where, in order to finally escape the pursuit of Rome, he took his own life in 183 BCE.

Scipio, meanwhile, was also abused by his countrymen who – forgetting how much they owed him – accused him of being a Carthaginian sympathizer in pardoning Hannibal, of accepting bribes, and misusing funds. He retreated to his estate in Liternum and was so disgusted by Rome's ingratitude that he left instructions in his will that he be buried there instead of in a place of honor within the city. He died of natural causes the same year Hannibal committed suicide.

The Battle of Zama not only ended the Second Punic War but it also established the Roman army as the greatest fighting force since the armies of Alexander the Great. At the Battle of Cannae, Rome had relied on traditional tactics using superior numbers to crush an enemy, and from that defeat, Scipio understood that new arts of war were necessary. After Scipio's brilliant reforms to Roman military strategy and tactics, the Romans would go on to conquer the known world. Zama, then, was not only the end of the Second Punic War but the beginning of effective campaigns of conquest which would eventually launch the Roman Empire.