The practice of mummifying the dead began in ancient Egypt c. 3500 BCE. The English word mummy comes from the Latin mumia which is derived from the Persian mum meaning 'wax' and refers to an embalmed corpse which was wax-like. The idea of mummifying the dead may have been suggested by how well corpses were preserved in the arid sands of the country.

Early graves of the Badarian Period (c. 5000 BCE) contained food offerings and some grave goods, suggesting a belief in an afterlife, but the corpses were not mummified. These graves were shallow rectangles or ovals into which a corpse was placed on its left side, often in a fetal position. They were considered the final resting place for the deceased and were often, as in Mesopotamia, located in or close by a family's home.

Graves evolved throughout the following eras until, by the time of the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE), the mastaba tomb had replaced the simple grave, and cemeteries became common. Mastabas were seen not as a final resting place but as an eternal home for the body. The tomb was now considered a place of transformation in which the soul would leave the body to go on to the afterlife. It was thought, however, that the body had to remain intact in order for the soul to continue its journey.

Once freed from the body, the soul would need to orient itself by what was familiar. For this reason, tombs were painted with stories and spells from The Book of the Dead, to remind the soul of what was happening and what to expect, as well as with inscriptions known as The Pyramid Texts and Coffin Texts which would recount events from the dead person's life. Death was not the end of life to the Egyptians but simply a transition from one state to another. To this end, the body had to be carefully prepared in order to be recognizable to the soul upon its awakening in the tomb and also later.

The Osiris Myth & Mummification

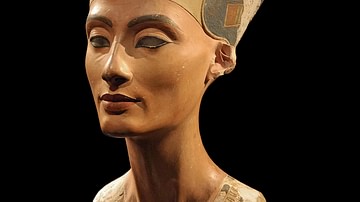

By the time of the Old Kingdom of Egypt (c. 2613-2181 BCE), mummification had become standard practice in handling the deceased and mortuary rituals grew up around death, dying, and mummification. These rituals and their symbols were largely derived from the cult of Osiris who had already become a popular god. Osiris and his sister-wife Isis were the mythical first rulers of Egypt, given the land shortly after the creation of the world. They ruled over a kingdom of peace and tranquility, teaching the people the arts of agriculture, civilization, and granting men and women equal rights to live together in balance and harmony.

Osiris' brother, Set, grew jealous of his brother's power and success, however, and so murdered him; first by sealing him in a coffin and sending him down the Nile River and then by hacking his body into pieces and scattering them across Egypt. Isis retrieved Osiris' parts, reassembled him, and then with the help of her sister Nephthys, brought him back to life. Osiris was incomplete, however - he was missing his penis which had been eaten by a fish - and so could no longer rule on earth. He descended to the underworld where he became Lord of the Dead. Prior to his departure, though, Isis had mated with him in the form of a kite and bore him a son, Horus, who would grow up to avenge his father, reclaim the kingdom, and again establish order and balance in the land.

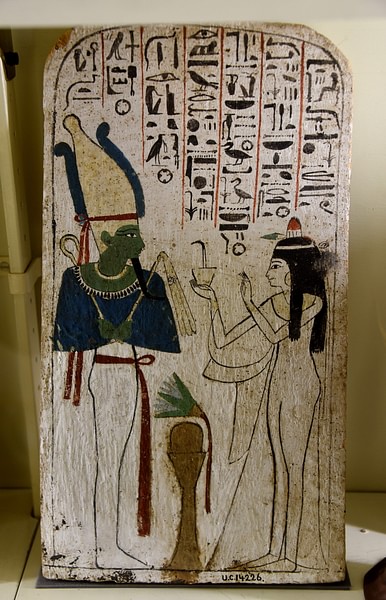

This myth became so incredibly popular that it infused the culture and assimilated earlier gods and myths to create a central belief in a life after death and the possibility of resurrection of the dead. Osiris was often depicted as a mummified ruler and regularly represented with green or black skin symbolizing both death and resurrection. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson writes:

The cult of Osiris began to exert influence on the mortuary rituals and the ideals of contemplating death as a "gateway into eternity". This deity, having assumed the cultic powers and rituals of other gods of the necropolis, or cemetery sites, offered human beings salvation, resurrection, and eternal bliss. (172)

Eternal life was only possible, though, if one's body remained intact. A person's name, their identity, represented their immortal soul, and this identity was linked to one's physical form.

Parts of the Soul

The soul was thought to consist of nine separate parts:

- The Khat was the physical body.

- The Ka one's double-form (astral self).

- The Ba was a human-headed bird aspect which could speed between earth and the heavens (specifically between the afterlife and one's body)

- The Shuyet was the shadow self.

- The Akh was the immortal, transformed self after death.

- The Sahu was an aspect of the Akh.

- The Sechem was another aspect of the Akh.

- The Ab was the heart, the source of good and evil, holder of one's character.

- The Ren was one's secret name.

The Khat needed to exist in order for the Ka and Ba to recognize itself and be able to function properly. Once released from the body, these different aspects would be confused and would at first need to center themselves by some familiar form.

The Embalmers & Their Services

When a person died, they were brought to the embalmers who offered three types of service. According to Herodotus: "The best and most expensive kind is said to represent [Osiris], the next best is somewhat inferior and cheaper, while the third is cheapest of all" (Nardo, 110). The grieving family was asked to choose which service they preferred, and their answer was extremely important not only for the deceased but for themselves.

Obviously, the best service was going to be the most expensive, but if the family could afford it and yet chose not to purchase it, they ran the risk of a haunting. The dead person would know they had been given a cheaper service than they deserved and would not be able to peacefully go on into the afterlife; instead, they would return to make their relatives' lives miserable until the wrong was righted. Burial practice and mortuary rituals in ancient Egypt were taken so seriously because of the belief that death was not the end of life. The individual who had died could still see and hear, and if wronged, would be given leave by the gods for revenge.

The Mummification Process

It would seem, however, that people still chose the level of service they could most easily afford. Once chosen, that level determined the kind of coffin one would be buried in, the funerary rites available, and the treatment of the body. Egyptologist Salima Ikram, professor of Egyptology at the American University at Cairo, has studied mummification in depth and provides the following:

The key ingredient in the mummification was natron, or netjry, divine salt. It is a mixture of sodium bicarbonate, sodium carbonate, sodium sulphate and sodium chloride that occurs naturally in Egypt, most commonly in the Wadi Natrun some sixty four kilometres northwest of Cairo. It has desiccating and defatting properties and was the preferred desiccant, although common salt was also used in more economical burials. (55)

In the most expensive type of burial service, the body was laid out on a table and washed. The embalmers would then begin their work at the head:

The brain was removed via the nostrils with an iron hook, and what cannot be reached with the hook is washed out with drugs; next the flank is opened with a flint knife and the whole contents of the abdomen removed; the cavity is then thoroughly cleaned and washed out, firstly with palm wine and again with an infusion of ground spices. After that it is filled with pure myrrh, cassia, and every other aromatic substance, excepting frankincense, and sewn up again, after which the body is placed in natron, covered entirely over for seventy days – never longer. When this period is over, the body is washed and then wrapped from head to foot in linen cut into strips and smeared on the underside with gum, which is commonly used by the Egyptians instead of glue. In this condition the body is given back to the family who have a wooden case made, shaped like a human figure, into which it is put. (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus)

In the second-most expensive burial, less care was given to the body:

No incision is made and the intestines are not removed, but oil of cedar is injected with a syringe into the body through the anus which is afterwards stopped up to prevent the liquid from escaping. The body is then cured in natron for the prescribed number of days, on the last of which the oil is drained off. The effect is so powerful that as it leaves the body it brings with it the viscera in a liquid state and, as the flesh has been dissolved by the natron, nothing of the body is left but the skin and bones. After this treatment, it is returned to the family without further attention. (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus)

The third and cheapest method of embalming was "simply to wash out the intestines and keep the body for seventy days in natron" (Ikram, 54, citing Herodotus). The internal organs were removed in order to help preserve the corpse, but because it was believed the deceased would still need them, the viscera were placed in canopic jars to be sealed in the tomb. Only the heart was left inside the body as it was thought to contain the Ab aspect of the soul.

Embalmer's Methods

The embalmers removed the organs from the abdomen through a long incision cut into the left side. In removing the brain, as Ikram notes, they would insert a hooked surgical tool up through the dead person's nose and pull the brain out in pieces but there is also evidence of embalmers breaking the nose to enlarge the space to get the brain out more easily. Breaking the nose was not the preferred method, though, because it could disfigure the face of the deceased and the primary goal of mummification was to keep the body intact and preserved as life-like as possible. This process was followed with animals as well as humans. Egyptians regularly mummified their pet cats, dogs, gazelles, fish, birds, baboons, and also the Apis bull, considered an incarnation of the divine.

The removal of the organs and brain was all about drying out the body. The only organ they left in place, in most eras, was the heart because that was thought to be the seat of the person's identity and character. Blood was drained and organs removed to prevent decay, the body was again washed, and the dressing (linen wrapping) applied.

Although the above processes are the standard observed throughout most of Egypt's history, there were deviations in some eras. Bunson notes:

Each period of ancient Egypt witnessed an alteration in the various organs preserved. The heart, for example, was preserved in some eras, and during the Ramessid dynasties the genitals were surgically removed and placed in a special casket in the shape of the god Osiris. This was performed, perhaps, in commemoration of the god's loss of his own genitals or as a mystical ceremony. Throughout the nation's history, however, the canopic jars were under the protection of the Mesu Heru, the four sons of Horus. These jars and their contents, the organs soaked in resin, were stored near the sarcophagus in special containers. (175)

Funeral Rites & Burial

Once the organs had been removed and the body washed, the corpse was wrapped in linen - either by the embalmers, if one had chosen the most expensive service (who would also include magical amulets and charms for protection in the wrapping), or by the family - and placed in a sarcophagus or simple coffin. The wrapping was known as the 'linen of yesterday' because, initially, poor people would give their old clothing to the embalmers to wrap the corpse in. This practice eventually led to any linen cloth used in embalming known by the same name.

The funeral was a public affair at which, if one could afford them, women were hired as professional mourners. These women were known as the 'Kites of Nephthys' and would encourage people to express their grief through their own cries and lamentation. They would reference the brevity of life and how suddenly death came but also gave assurance of the eternal aspect of the soul and the confidence that the deceased would pass through the trial of the weighing of the heart in the afterlife by Osiris to pass on to paradise in the Field of Reeds.

Grave goods, however rich or modest, would be placed in the tomb or grave. These would include shabti dolls who, in the afterlife, could be woken to life through a spell and assume the dead person's tasks. Since the afterlife was considered an eternal and perfect version of life on earth, it was thought there was work there just as in one's mortal life. The shabti would perform these tasks so the soul could relax and enjoy itself. Shabti dolls are important indicators to modern archaeologists on the wealth and status of the individual buried in a certain tomb; the more shabti dolls, the greater the wealth.

Besides the shabti, the person would be buried with items thought necessary in the afterlife: combs, jewelry, beer, bread, clothing, one's weapons, a favorite object, even one's pets. All of these would appear to the soul in the afterlife and they would be able to make use of them. Before the tomb was sealed, a ritual was enacted which was considered vital to the continuation of the soul's journey: the Opening of the Mouth Ceremony. In this rite, a priest would invoke Isis and Nephthys (who had brought Osiris back to life) as he touched the mummy with different objects (adzes, chisels, knives) at various spots while anointing the body. In doing so, he restored the use of ears, eyes, mouth, and nose to the deceased.

The son and heir of the departed would often take the priest's role, thus further linking the rite with the story of Horus and his father Osiris. The deceased would now be able to hear, see, and speak and was ready to continue the journey. The mummy would be enclosed in the sarcophagus or coffin, which would be buried in a grave or laid to rest in a tomb along with the grave goods, and the funeral would conclude. The living would then go back to their business, and the dead were then believed to go on to eternal life.