The fullers of ancient Rome were launderers who washed the clothes of the city and also finished processing fabric later made into clothing, blankets, or other necessary items. They were looked down upon for their use of human and animal urine as a detergent but were among the most successful and highly-paid workers in the city.

The occupation of fuller had a long history, dating back to Mesopotamia long before c. 1600 BCE when it is famously referenced in the Sumerian comedy At the Cleaners. The occupation was among the most essential in Egypt, held the same importance in Greece, and is mentioned in the Bible where, among other references, fullers are cited in the Transfiguration of Jesus in Mark 9:3 when his robes become a dazzling white "as no fuller on earth can white them." This line references one of the fullers’ primary responsibilities – cleaning clothes – and to get them as bright as possible they used urine as a natural bleaching agent.

Urine was collected from public restrooms and the fullers' near-obsession with gathering as much as possible associated them with waste and filth far more than cleanliness. The urine was poured into a vat with the clothing and the fullers (or their slaves) would tread on the cloth, agitating it the way a modern-day washing machine does, to remove stains and odors. This profession continued, operating in the same way with the same cleaning agents, for hundreds of years after the fall of the Roman Empire and up into the modern age when soap replaced urine. Present-day professional launderers carry on the ancient tradition which is among the oldest in the world.

Roman Clothing & Laundry

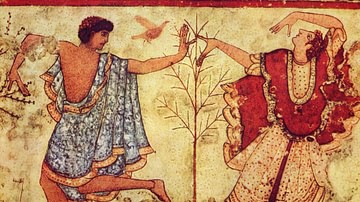

The upper-class Romans were well aware of how clothes reflect one’s status and were careful to cultivate an impressive public image. Even their house-slaves and servants were well dressed and, it seems, the lower classes were equally aware of the importance of looking one’s best outside the home. Roman clothing is thought to have developed from ancient Greek clothing, which allowed for the creation of multiple outfits using one garment that could be arranged differently on the body.

As in Greece, Roman clothing was unisex, and children simply wore smaller versions of adult outfits (usually just a tunic for both boys and girls). The basic garments were:

Underwear – loincloths for men and women and a breastband like the Greek strophion for women, a cloth which supported the breasts and tied at the back.

Tunics – knee-length sleeveless garments secured at the shoulders by brooches (or sewn) and at the waist by a belt of leather or cloth. Some tunics were floor-length and long-sleeved, but most were cut short to allow greater freedom of movement. The basic white tunic would be dyed to indicate one’s status or occupation, just as with the toga, and members of sports teams would have their tunics all dyed the same color (as would some of their fans). Some styles of tunic, with longer sleeves and varying necklines, were favored by male and female prostitutes who might also have them dyed to attract more attention.

Trousers – usually only worn by soldiers, especially cavalry, and gladiators

Togas – the well-known outer garment of the upper-class Roman, usually associated with men but also worn by women. The toga was worn over a tunic or on its own. Scholars Lesley and Roy A. Adkins comment:

The toga was an expensive, heavy garment of fine natural white wool, and required frequent cleaning by the fuller. It was roughly semicircular in shape, about 5.5 m (18 ft) wide and 2.1 (7 ft) deep. It had to be draped in a complicated manner around the body, and several emperors had to issue decrees to enforce its use on public occasions [because it was such a bother]…The toga showed differences in the social order. The toga praetexta (bordered toga) had a purple stripe and was worn by magistrates. (344)

Other togas had different colored stripes signifying the social status of the wearer. An upper-class single woman would have worn a tunic until puberty when she was expected to put away all things associated with childhood and become a woman. At this time, she would have worn a simple white toga, perhaps over a tunic. Married women wore a tunic under a full-length dress known as a stola. Adkins comments:

Women also wore cloaks. The clothes of the wealthy were in rich colors and fine materials, such as muslins and silks. In some areas, women also wore close-fitting bonnets and hairnets. (345)

Men, of course, also wore cloaks and capes made of wool or leather and these, just like all of the above, had to be cleaned regularly. The Romans did not bathe or do laundry at home. Most of the citizens could not have done so even if they wanted to because they lived in apartment buildings (insula) which were usually dark, poorly ventilated, and, in most cases, had no running water. Aqueducts, that brought water into the city, usually fed public fountains, pools, businesses, and Roman baths, not private residences.

Every free person in the city, therefore, had to bring their clothes to the fullers to be cleaned, but besides their primary function, the fuller also dyed the tunics, capes, and togas, pleated the married woman’s stola, and finished off the process of readying a fabric to be made into a garment or felting a garment so it would be waterproof.

The Process

They were called upon for all these tasks, but regularly for cleaning soiled clothing. The process had three steps which are essentially the same as laundering today, only done with different materials and agents. A client would bring their clothes to the fullonica (plural: fullonicae) and leave them with the fuller (Latin: fullones – a bleacher/cleaner of clothing) with instructions on what was to be done with each article or the whole bundle.

The fuller was completely responsible for the clothes while they were in his possession and if he lost or damaged one he was answerable under the law to replace it, which could be quite expensive. The clothing of a given client was kept together throughout the process so none of it would become mixed up with another and mistakenly given to someone else once the process was completed. Woolen garments, especially, were handled with care because they were thought to lose their initial quality after being washed once and go down in worth each time they went to the fullers afterwards. Even so, clients continued to bring their clothes to the shops simply because they had no choice. Rome was not the cleanest of cities nor the freshest smelling, and fullers’ shops were in operation almost every day of the year except during certain festivals. Once the clothes were accepted by the fuller, the process began:

Washing: The fuller would put the clothes in a vat (or vats) which were anchored to the floor or a raised platform and then add water and urine before stepping in himself. The vats were divided from each other by low walls, which the fuller would use to keep balance as he trod around on the clothing with his bare feet. How long the washing part of the process continued is unknown.

Rinsing: The clothes were removed from the washing vats and squeezed out either by hand or through a corkscrew press and then beaten with a stick to loosen any dirt remaining. They were then dumped into the rinsing bowls which were supplied with clean water from the city’s central system. If a stain was still apparent, the process started again while, if all the clothes looked properly cleaned, they were moved to the drying area.

Drying: Garments were again squeezed out by hand or through a corkscrew press and then spread on racks in an open area to dry. As they dried, they were brushed to remove any lint, and then all-white clothing was set on wicker frames over burning sulphur to bleach them; colored clothing was rubbed with the natural substance known as fullers’ earth which helped restore color, maintained the quality of the cloth, and removed any lingering stain. Once the white clothes were done bleaching, they were also rubbed with fullers’ earth.

Once cleaned and dried, the clothes were, presumably, tagged with the client's name for pickup or delivery depending on what arrangements had been made. The fuller then continued the process with the next client. Vats for dyeing were, naturally, separate from those used for washing or rinsing and there was a separate area for felting cloth. In large fullonicae, there were many workers cleaning, rinsing, drying, dyeing, and felting all at once, but even in more modest shops there were usually a few slaves performing the actual labor with the owner handling public relations and the running of the business.

The Fullonica of Stephanus

The most perfectly preserved shop of this kind is the Fullonica of Stephanus uncovered at Pompeii between 1912-1914. The fullonica was discovered during excavations of the avenue Via dell’Abbondanza, one of the city’s main roads, as one of the businesses in the cluster of buildings now known as City Block 6. The block had private homes, some of two storeys, which opened on the front onto the Via dell’Abbondanza and at the back onto gardens and a smaller thoroughfare.

There were two shops of unknown purpose at either end of the block, which were presumably owned and either operated or rented out by the people who lived in the houses/apartments connected to them. Right next to the fullonica was a thermopolium, a fast-food restaurant, which had a section corresponding to a modern-day snack bar toward the front and one for sit-down dining toward the back. The thermopolium is thought to have been owned by the resident of the adjacent home whose door opened into it and whose back door led to the gardens and smaller road behind the block.

Excavations at the site suggested the fullonica had been a home, the lower level of the residence attached to it, owned by one Stephanus. Scholar Brian K. Harvey comments:

The establishment had the floor plan of a typical house, but basins and vats for cleaning the clothes were added to the house’s small atrium and peristyle, indicating that it was converted from a house into a fullery. (169)

Stephanus was clearly a successful businessman, since there is evidence he had a number of employees or slaves who did the actual work of cleaning clothing while Stephanus ran the business, in keeping with the usual model of a fullonica. The official website of Pompeii agrees with Harvey’s conclusion that the shop was a converted home and also notes how excavations uncovered the remains of its owner:

This production facility, designed for the washing of dirty laundry and degreasing fabric that had just been threaded, was built in the last stage of the life of the city, transforming the structure from an original house to an atrium. A large bath was placed at the center of the atrium…and a skylight was placed so as to use the upper part as a terrace to dry the laundry and other baths were placed in the garden at the back of the house. When the excavators exposed the laundry, a skeleton was found near the entrance which bore a hoard of coins. Based on electoral inscriptions, it is supposed that Stephanus was the owner of the fullery who died during the eruption in 79 AD while trying to escape with the latest collections. (1)

The Fullonica of Stephanus is typical of an industrial laundry of ancient Rome as evidenced by similar sites excavated in Rome itself and nearby Ostia. Ten other fullonicae have been discovered at Pompeii, almost all of them smaller than Stephanus’ shop, which suggests his shop may have been the most popular and profitable. Its location on the busy Via dell’Abbondanza would be comparable to any successful business in a strip mall on a busy urban thoroughfare in the present day.

Social Status of Fullers

Although fullers performed an essential job for the people of the city, they were generally looked down upon primarily because of their seeming preoccupation with acquiring urine. Harvey comments:

The most important detergent used in the fullery process was animal or human urine because of its quality as a natural bleaching agent. Urine was collected from public urinals, small jars set in the streets around town. Urine was precious to the fullers, and their zealous use of it was one of the main reasons for their unpopular reputation as personae non gratae around town. The urine the fullers needed was so valuable, in fact, that the emperor Vespasian put a tax on its use. (209)

Even so, many fullers lived comfortable lives and had enough disposable income to contribute to public building efforts and festivals. The patron deity of the fullers was Minerva due to her association with weaving and crafts and the fullers celebrated her festival of the Quinquatria in their shops every year on 19 March (or 19-23 March when it was extended) and were able to contribute to the food and drink for the celebration. The fullers were also powerful enough to establish their own guild and be able to set their own prices. Harvey notes:

Despite the bad reputation of those who worked in the trade, fulling was a thriving industry in the ancient city…Many were wealthy enough to provide a decent burial for themselves and their families. (209)

The location and size of the fullonica of Stephanus is the best example of how successful a fuller could be, but it is not the only one. All the free people of Rome, and throughout the Roman Empire, needed clean clothing and, as noted, were unable or unwilling to do the job themselves. It is unknown how much a fuller was paid for services, but all evidence suggests they did quite well for themselves.

Conclusion

The fullers were only one of a number of essential occupations in Rome which other people scorned but could not have done without. Sanitation workers, for example, who cleaned the streets and maintained the sewers, were also socially shunned or at least mocked behind their backs but were also a critical part of an urban industrial complex, which could not have functioned as well as it did without them. Adkins writes:

Most Roman industries were like well-organized crafts and there was no distinction between a craft and an industry. They were labor-intensive, often very skilled, and localized, although some goods were traded extensively. Industries varied in their organization, from large-scale production for trade to very small-scale production to meet local needs in what would now be termed a craft industry. (314)

The fullers meet Adkins’ description of Roman industry on every level as a fullonica could be large, serving a wide area, or a small shop which only took in clothing from the surrounding neighborhood. They were so integral to the functioning of society that, after the fall of the Western Roman Empire c. 476 CE, fullers continued to operate in Rome as they had before. The industry not only survived but thrived for centuries, replacing urine with soap and detergent at some point during the Renaissance Period. The occupation is still proudly practiced by people today who find themselves just as indispensable to their clientele as the fullers of ancient Rome did theirs.