A famous story from Greece relates how a young woman named Agnodice wished to become a doctor in Athens but found this forbidden. In fact, a woman practicing medicine in Athens in the 4th century BCE faced the death penalty. Refusing to give up on her dreams, she traveled to Alexandria where women were routinely allowed in the medical profession. Once she had received her training, she returned to Athens to practice but did so disguised as a man. When she was found to be a woman 'pretending' to be a doctor she was brought to trial charged with a capital crime until she was saved by her female patients who stormed the proceedings and shamed the prosecuting males into releasing her.

Following Agnodice's trial, the laws were changed in Athens so women could now practice medicine, but by this time, female physicians were known in Egypt for centuries. The evidence for women in the medical field in Egypt, however, has been largely ignored by historians for the past century. Even so eminent an Egyptologist as Barbara Watterson claims that physicians in Egypt "were all, with one or two exceptions, male" (46). This claim, and others like it, flatly ignores evidence of women in the medical profession going back to the Early Dynastic Period in Egypt (c. 3150 - c. 2613 BCE) when Merit-Ptah was the royal court's chief physician c. 2700 BCE. Merit-Ptah is the first female doctor known by name in world history, but evidence suggests a medical school at the Temple of Neith in Sais (a city in Lower Egypt) run by a woman whose name is unknown c. 3000 BCE.

Egyptian Value of the Feminine

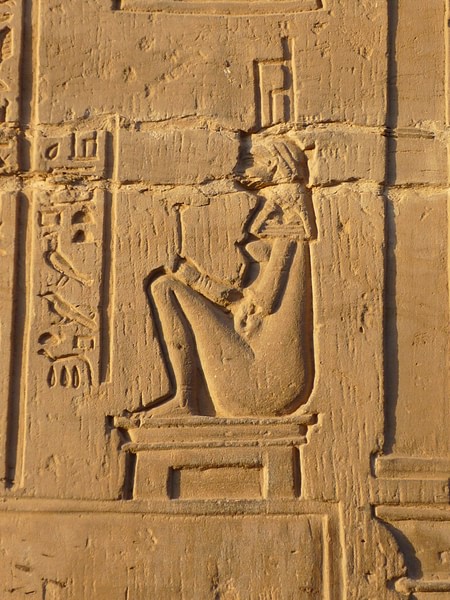

Female physicians do not appear in Egyptian history as frequently as males, and there is no doubt that men dominated the medical field. This does not mean, however, that there were no female doctors nor should it seem at all strange to find women in the medical profession in ancient Egypt. Women were highly respected throughout Egypt's history, and feminine symbols appear early. Scholars identify the symbol of the tjet or tyet (also known as 'The Knot of Isis' or 'Blood of Isis' and dating from the Old Kingdom (c. 2613 - c. 2181 BCE) as the feminine counterpart to the ankh (dating from the Early Dynastic Period), and many of the major deities of the Egyptian Pantheon were female.

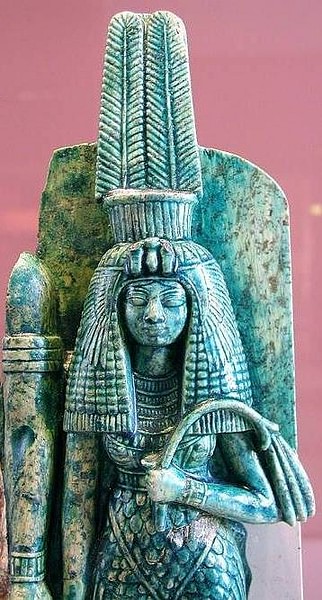

Neith is one of the most ancient goddesses in the world and among the earliest worshiped in Egypt. She is associated with creation in some myths and with the invention of birth as well as being linked with war, death, and the afterlife. One of the most popular and influential myths of Egypt is the story of Osiris and Isis in which Isis plays the dominant role. The goddess Hathor, presiding over joy, festivities, fertility, and many other bright aspects of life, was worshiped by both sexes as was Bastet, keeper of the hearth, home, and women's secrets. Of the four deities most commonly associated with healing (Heka, Sekhmet, Serket, and Nefertum) two are female. The god Sobek, though also linked with healing, was more closely associated only with the aspects of surgery. The deity who presided over writing was the goddess Seshat, who was also the librarian of the gods. The recurring motif of the Distant Goddess in Egyptian myth, in which transformation is realized, is obviously associated with the feminine, and goddesses such as Qebhet and Nephthys play important roles in the mortuary rituals and the afterlife. The most important cultural value of Egyptian civilization was harmony and balance, symbolized by the goddess Ma'at and her white ostrich feather.

Egyptian culture is infused with feminine power and women were accorded almost equal rights and standing. Women could own land, initiate divorce, own businesses, and become priestesses and scribes. Doctors were all scribes, one of the most respected and affluent of the social classes, though not all scribes became doctors. Even though there persist scholars in the present day who claim women were not allowed to become scribes, the established female presence in the medical profession - as well as other evidence - argues otherwise. Doctors needed to be able to read the medical texts and spells as well as write them in order to care for their patients who were prone to a variety of illnesses.

Disease & Treatment

The ancient Egyptians suffered from many of the same maladies as people in the present day. Egyptologist Joyce Tylldelsy writes:

The idyllic scenes which decorate many tomb walls give the impression that the Egyptians were a fit and healthy race untroubled by sickness. This impression is flatly contradicted by the medical evidence which indicates a population at the mercy of a wide variety of debilitating and life-threatening diseases...Even less serious-sounding afflictions such as diarrhoea, coughs, and cuts could prove fatal without modern medicines, while the majority of the population suffered intermittently from painful rheumatoid joints and badly abcessed teeth. (31)

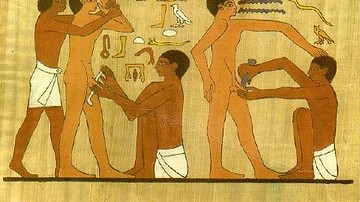

Doctors treated physical injury with straightforward methods of bandaging wounds and setting broken bones, but disease was more difficult to diagnose. Sickness was considered a punishment sent by the gods, an attack by an angered ghost or demon, a trial through which one should learn a lesson, or a manifestation of some evil spirit.

These supernatural forces were thought to result in a number of illnesses which could be cured by magic spells, rites, and incantations, but this did not mean the doctor had the ability to banish disease entirely. The supernatural world was beyond any mortal's control, and all a doctor could do was treat each individual case as it presented. According to Barbara Watterson, Egyptian doctors were originally 'magicians' who dealt primarily with the supernatural but eventually came to combine empirical observation and technique with magic spells. Egyptologist Rosalie David comments on this, writing:

Doctors were specialized priests who had originally acted as religious mediators between the god and the patient but, over the centuries, they acquired detailed medical knowledge and experience. Even as early as the Old Kingdom, the medical profession appears to have been highly organized and incorporated rational as well as magical treatment of patients. Little is known of the medical training and whether it was entirely practical or whether the students had to pass examinations. The temples appear to have played an important part both in medical training and the healing of patients. The "House of Life" was an area of the temple that, as a center of documentation where sacred papyri were written or copied, may also have been used as a teaching center for medical students. (336)

The House of Life was also considered the medical knowledge the individual doctors had acquired and carried with them. These physicians often operated out of the temple complex and, just as often, made house calls. Many of these doctors are known by name and some of them were women.

Merit-Ptah & Peseshet

The Egyptians were famous as skilled healers as early as 800 BCE, and women were already associated with the art. In Homer's Odyssey, Polydamna, "wife of Thon, a woman of Egypt," gives Helen the drug that "banishes all care, sorrow, and ill-humor," and it is further noted in the same passage that everyone in Egypt is a skilled physician (IV.228). The 'first physician' of the Early Dynastic Period/Old Kingdom of Egypt was the architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE), best known for creating Djoser's Step Pyramid and his medical works arguing for disease as a natural occurrence, not a punishment from the gods. He was later deified as a god of healing and medicine. Two women from around his same time were also noted for their medical practice and achievements, even though today they seem the most famous Egyptian doctors no one has ever heard of.

The first female physician in Egyptian history, as noted above, is Merit-Ptah ('Beloved of Ptah') who lived c. 2700 BCE toward the end of the Early Dynastic Period. She was not the only woman of note from this time as the Queen Merneith (c. 2900 BCE) definitely ruled as regent and possibly on her own. Merit-Ptah is not only the first female doctor known by name but the first woman mentioned in the study of science. Her inscription, left by her son, was found on a tomb at Saqqara naming her 'Chief Physician' a position which would have made her a teacher and supervisor of males. As chief physician, she would have also attended the king, but exactly which king is uncertain because the 2nd Dynasty records are poorly preserved.

Peseshet (c. 2500 BCE) was known as 'Lady Overseer of Female Physicians' and may have been associated with the temple-school at Sais. She has also been cited as the first female doctor known by name, but it is unclear whether she was best known as a practicing physician or a teacher. Peseshet is referred to in inscriptions as the 'King's Associate,' which suggests she was the personal physician of the monarch. She is also associated with the training of midwives, one of the few references to such training in Egyptian history. All of the information about her comes from her stela at Giza, and though this is scant, it does establish Peseshet as a medical practitioner and also makes clear there were other female physicians practicing at the time whom she supervised or trained.

Peseshet would have lived and worked during the 4th Dynasty in the period of the Old Kingdom. During this time, the central government was strong and kept careful records as well as correspondence, but there is no mention of Peseshet in any of them. This is not surprising, however, since there is little mention, by name, of any physicians, female or male. After Peseshet, no women are cited as practicing physicians again until the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE), but this is not to say there were none. Midwives also cease to be mentioned after the Old Kingdom, but it is clear their position continued and was considered quite important.

Women in the Medical Field

In the medical field, women are mentioned as nurses and depicted as midwives. Males and females were nurses who assisted the doctors in procedures. Nurses also played an important role in the life of the king. Egyptologist Carolyn Graves-Brown writes:

In the New Kingdom, at least, the royal nurse was an important person, being so close to the king. Despite the fact that women's occupations are rarely shown in the tombs of their male relatives, tomb owners often show their female relatives in the role of nurses to the king. Hatshepsut's nurse, Sitre, was important enough to be buried near her queen. Nurses also seem to have been held in high regard by the non-royal elite, as they are shown in private tomb chapels and on stelae with the family. (83)

Queen Hatshepsut (1479-1458 BCE) founded medical schools and encouraged women to pursue medicine. Other New Kingdom queens are also thought to have encouraged the same, notably Queen Tiye (1398-1338 BCE) and Nefertiti (c. 1370- c. 1336 BCE), both of whom are noted for their social programs. As far as any official record is concerned, however, there is no evidence for this. Aside from the position of nurse, women in medicine are recorded as midwives and wet nurses.

The wet nurse was an especially important role considering the high mortality rate of women in childbirth. Legal documents establish agreements between women and expectant parents to care for the newborn should the mother die. Graves-Brown notes how these agreements "stipulate that a wet nurse was to have a trial run before being hired; she was obliged to provide milk of a suitable quality, not to nurse any other children, and not to fall pregnant or enter into sexual activity" (83). In return, the employer would pay the nurse and also provide oil for use in massaging the newborn child.

The Ptolemaic Period & Later

Legend links Queen Cleopatra VII (69-30 BCE) with the medical profession as the author of a book on the subject; most likely, however, she simply continued the policies of earlier queens such as Hatshepsut and sponsored such works. Her name has been linked to the famous Roman physician Galen (126 - c. 216 CE), who lived long after her, and this is because of another, lesser-known, Cleopatra.

This other Cleopatra is regularly referenced as living c. 2nd century CE, but it seems clear she lived earlier, probably during the Ptolemaic Period, and was cited in works from the later time. This Cleopatra was known for authoring a book on obstetrics which was regularly consulted by doctors, including Galen. It is probable that later writers confused the physician Cleopatra with the monarch but also possible they knew of the queen's involvement in medical matters better than later historians who wrote on her. Scholar Okasha El Daly comments on this, writing:

It may have been the fame of Queen Cleopatra, either as an author of medical books or due to her patronage of such works which Galen consulted, that gave rise to this claim in Arab sources of a connection between him and Cleopatra as his teacher. (115)

Women in Egypt continued to exercise authority in medicine and the sciences until the triumph of Christianity in the country in the 4th century CE. The clearest evidence of this is seen in the life of Hypatia of Alexandria (c. 370-415 CE), the philosopher who instructed her largely male students in philosophy and science until she was murdered by a Christian mob.

The claim that there were no women, or only a few, involved in medicine in ancient Egypt is untenable and does not accord with the values of the civilization. By this reasoning, there were no women involved in anything of note anywhere in the world until the modern era because history books make no mention of their contributions. This point is made clear in Virginia Woolf's brilliant essay Shakespeare's Sister from A Room of One's Own in which she imagines the life of the playwright's equally gifted sister in a society which did not value women. Although Elizabethan England was ruled by a queen, opportunities for women of the time were few; unlike in ancient Egypt. Female physicians' names may be largely missing from Egypt's historical record, but this same can be said for most of recorded history. Unlike the histories of other cultures, however, it is clear that women in Egypt could hold positions of importance and respect and further that a number of them did.