In Europe, in the 19th century CE, an interesting device began appearing in graveyards and cemeteries: the mortsafe. This was an iron cage erected over a grave to keep the body of the deceased safe from 'resurrectionists' - better known as body-snatchers. These men would dig up freshly interred corpses and deliver them, for cash, to doctors wishing to study anatomy. Dissection of a human being was illegal at the time, and until the Anatomy Act of 1832 CE, the only corpses a doctor could work with were those who had been executed for capital crimes.

These did not provide physicians with the number of corpses, nor the assortment of causes of death, they required to better understand anatomy, physiology, and pathology. Doctors recognized that the best way to treat a patient was to understand how the organs of the body worked together and what could affect them, but they were denied access. These physicians paid the resurrectionists large sums of money over the years for dead bodies and would most likely have been surprised or even amused to learn that, in ancient Egypt, the practice of dissection was routine but that no one in the medical field of the time thought to take advantage of it.

The ancient Egyptian embalmers did not discuss their work with the doctors of the time, and the doctors never seem to have given a thought to inquire of the embalmers. Physicians in Egypt healed their patients through spells, practical medical techniques, incantations, and the use of herbs and other naturally occurring substances. Their understanding of anatomy and physiology was weak because although Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE) had argued that disease could be naturally occurring in his treatises, the prevailing understanding was that it was due to supernatural elements. A study of internal medicine, therefore, would have been considered a waste of time because sickness came to a person from external sources.

The Nature of Disease

Until the 19th century CE, the world had no understanding of germ theory. The work of Louis Pasteur, later confirmed by British surgeon Joseph Lister, proved that illness is caused by bacteria and steps can be taken to minimize one's risks. The ancient Egyptians, like every other civilization, had no such understanding. Disease was thought to be caused by the will of the gods (to punish sin or teach one a lesson), through the agency of an evil spirit or spirits, or brought on by the presence of a ghost.

Even in cases where a diagnosis suggested some definite physical cause for a problem, such as liver disease for example, this was still thought to have a supernatural origin. Egyptian medical texts recognize liver disease but not the function of the liver. In this same way, doctors understood the function of the uterus but not how it worked nor even its connection to the rest of a woman's body; they believed it was an organ with access to every other part of the body. The heart was considered the seat of intellect, emotion, and personality while the brain was believed to be useless, even though there are documented cases of brain surgery. It was understood that the heart was a pump and that veins and arteries moved blood through the body, and heart disease was diagnosed and treated by measures recognizable today (such as changing one's diet), but the root cause of the disease was still thought to come from supernatural agencies.

Famous Doctors

Even so, ancient Egyptian doctors were highly respected and for good reason: their procedures seem to have been largely effective. The Hittites are known to have called upon Egypt to supply them with physicians as did the Assyrians and Persians. The Greeks had enormous admiration for Egyptian medical practices, even though they did not take the magical aspects of treatment very seriously. The Roman physician Galen (126 - c. 216 CE) studied in Egypt at Alexandria, and before him, Hippocrates, the father of modern medicine (c. 460-370 BCE), made the same claims regarding disease that Imhotep had 2,000 years earlier.

Men and women could be doctors and a number are mentioned by name. Some of these are:

Merit-Ptah (c. 2700 BCE), the royal court's chief physician and the first woman known by name in medicine and science.

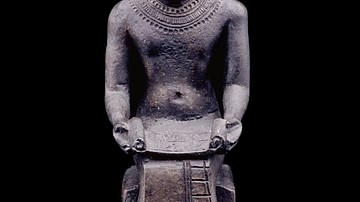

Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE), the architect for king Djoser who also wrote medical treatises and was later deified as a god of medicine and healing.

Hesyre (also known as Hesy-Ra, c. 2600 BCE), Chief of Dentists and Physician to the King; the first dentist in the world known by name.

Peseshet (c. 2500 BCE), Lady Overseer of Female Physicians and possibly a teacher at a medical school in Sais founded c. 3000 BCE.

Qar (c. 2350 BCE), Royal Physician under the reign of king Unas of the 6th Dynasty, buried with his bronze surgical instruments which are thought to be the oldest in the world.

Mereruka (c. 2345 BCE), Vizier under King Teti of the 6th Dynasty whose tomb at Saqqara is inscribed with more titles than any other in the vicinity. He was the overseer of the king's physicians.

Ir-en-akhty (First Intermediate Period of Egypt, 2181-2040), whose wide range of specialties makes him unique in Egyptian medical history. Most doctors specialized in a single area while Ir-en-akhty held many titles.

Other doctors are named from the Middle Kingdom (2040-1782 BCE) down through the Ptolemaic Period (323-30 BCE) including the physician Cleopatra (not the famous queen) who wrote medical texts which are mentioned by later writers and were studied by Galen.

Magic & Medicine

All these doctors practiced a combination of what one today would consider practical medicine and magic. Since disease came from supernatural sources, it was reasonable to conclude that supernatural treatment was the best recourse. In the present day, one may look back on these beliefs and practices with skepticism, but they were regarded as quite effective and entirely practical in their day.

Scholars and physicians in modern times are unable to substantiate just how effective they were because they are unable to positively identify the elements, diseases, and procedures mentioned in many of the texts. Some Egyptian words do not correspond to any known plant or object used in treatment or any known disease. Although the ancient Egyptian doctors did not have a full understanding of the functions of internal organs, they somehow managed to treat their patients well enough that their prescriptions and practices were copied and applied for millennia. The Greeks, especially, found Egyptian medical practices admirable. Plato mentions Egyptian doctors in his Dialogues and even swears by them as one would a god. The Greeks, in fact, served as the conduit through which Egyptian medical practices would reach a wider audience. Egyptologist Margaret Bunson explains:

The Greeks honored many of the early Egyptian priest-physicians, especially Imhotep, whom they equated with their god Asclepius. When they recorded the Egyptian medical customs and procedures, however, they included the magic and incantations used by the priests which made medicine appear trivial or a superstitious aspect of Egyptian life. Magical spells were indeed a part of Egyptian medicine...nevertheless, scholars have long recognized that the Egyptians carefully observed various ailments, injuries, and physical deformities, and offered many prescriptions for their relief. (158)

The god Heka presided over both medicine and magic and his staff of two entwined serpents would become the caduceus of Asclepius of the Greeks and, today, the symbol of the medical profession. Sekhmet, Serket (also Selket), Nefertum, Bes, Tawawret, and Sobek were all associated with health and healing in one aspect or another but so were powerful goddesses like Isis and Hathor and even those with darker personalities, usually feared, like Set or the demon-god Pazuzu. Any of these deities could be called upon by a medical practitioner to drive away evil demons, placate angry ghosts, rescind their choice to send the disease, or generate healing energies.

Treatments

The treatments prescribed usually combined some practical application of medicine with a spell to make it more effective. For example, a roasted mouse ground into a container of milk was considered a cure for whooping cough, but a ground mouse in milk taken after reciting a spell would work better. Mothers would bind their children's left hand with a sanctified cloth and hang images and amulets of the god Bes in the room for protection, but they also would recite the Magical Lullaby which drove off evil spirits.

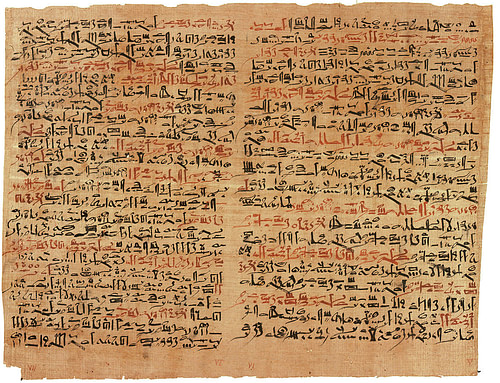

At the same time, there are a number of prescriptions which make no mention of magical spells. In the Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) a prescription for contraception reads: "grind together finely a measure of acacia dates with some honey. Moisten seed-wool with the mixture and insert into the vagina" (Lewis, 112). The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE) focuses on surgical treatment of injuries and, in fact, is the oldest known surgical treatise in the world. Although there are eight magical spells written on the back of the papyrus, these are thought by most scholars to be later additions since papyri were frequently used more than once by different authors.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus is the best known for practical procedures addressing injuries, but there are others which offer the same kind of advice for disease or skin conditions. Some of these were obviously ineffective - such as treating eye ailments with bat's blood - but others seem to have worked. Invasive surgery was never widely practiced simply because the Egyptian surgeons would not have considered this effective. Egyptologist Helen Strudwick explains:

Because of the limited knowledge of anatomy, surgery did not go beyond an elementary level and no internal surgery was undertaken. Most of the medical instruments found in tombs or depicted on temple reliefs were used to treat injuries or fractures which were possibly the result of accidents incurred by workers on the pharaohs' monumental building sites. Other implements were used for gynaecological problems and in childbirth, both of which were treated extensively in the medical papyri. (454)

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) is the oldest document of its kind dealing with women's health. Although spells are mentioned, many prescriptions have to do with administering drugs or mixtures without supernatural assistance, as in the following:

Examination of a woman bed-bound, not stretching when she shakes it,

You should say of it 'it is clenches of the womb'.

You should treat it by having her drink 2 hin of beverage and have her spew it up at once. (Column II, 5-7)

This particular passage illustrates the problem in translating ancient Egyptian medical texts since it is unclear what "not stretching when she shakes it" or "clenches of the womb" mean precisely, nor is it known what the beverage was. This is often the case with prescriptions where a certain herb or natural element or mixture is written as though it is common knowledge needing no further explanation. Beer and honey (sometimes wine) were the most common drinks prescribed to be taken with medicine. Sometimes the mix is carefully described down to the dose, but other times, it seems it was assumed the doctor would know what to do without being told.

Conclusion

As noted, the physicians of ancient Egypt were considered the best of their time and frequently consulted and cited by doctors of other nations. The medical school at Alexandria was legendary, and the great doctors of later generations owed their success to what they learned there. In the present day, it may seem quaint or even silly for people to believe that a magical incantation recited over a cup of beer could cure anything at all, but this practice seems to have worked well for the Egyptians.

It is entirely possible, as a number of scholars have suggested, that the success of the Egyptian doctor epitomizes the placebo effect: people believed their prescriptions would work, and so they did. Since the gods were so prevalent an aspect of Egyptian life, their presence in curing or preventing disease was no great leap of faith. The gods of the Egyptians did not live in the far-off heavens - although they certainly occupied that space as well - but on the earth, in the river, in the trees, down the road, in the temple in the city's center, at the horizon, noon, sunset, through life and on into death. When one considers the close relationship the ancient Egyptians had with their gods it is hardly surprising to find supernatural elements in their most common medical practices.