The ancient Egyptians experienced the same wide array of disease that people do in the present day, but unlike most people in the modern era, they attributed the experience to supernatural causes. The common cold, for example, was prevalent, but one's symptoms would not have been treated with medicine and bed rest, or not these alone, but with magical spells and incantations. The Ebers Papyrus (dated to c. 1550 BCE), the longest and most complete medical text extant, clearly expresses the Egyptian view of medical treatment: "Magic is effective together with medicine. Medicine is effective together with magic." The magic referred to took the form of spells, incantations, and rituals, which called on higher supernatural powers to cure the patient or treat symptoms.

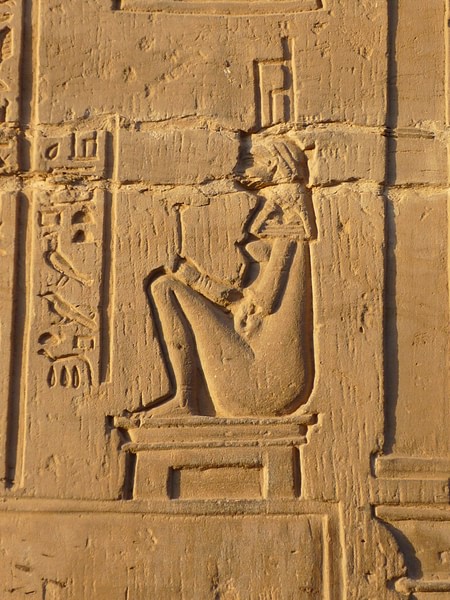

Heka was the god of magic and also of medicine, but there were a number of deities called upon for different diseases. Serket (Selket) was invoked for the bite of the scorpion. Sekhmet was called upon for a variety of medical problems. Nefertum would be appealed to in administering aroma therapy. Bes and Tawreret protected pregnant women and children. Sobek would intervene in surgeries. One could call upon any god for help, however, and Isis and Hathor were also invoked, as was the demon-god Pazuzu. Even Set, a god associated with chaos and discord, sometimes appears in magic spells because of his protective qualities and great strength. All of these deities, however, no matter how powerful, had to be called by an experienced practitioner and this was the doctor of ancient Egypt; part magician, part priest, and part physician.

Injury & Disease

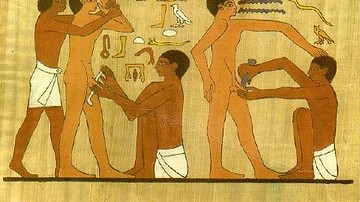

Physical injury was common in a culture which not only engaged in monumental building projects but had to contend with wild animal attacks from lions, hippos, jackals, and others. Injuries were easily recognized and treated in much the same way they would be today: bandages, splints, and casts. Since the Egyptians had no concept of bacteria or the germ theory, however, the cause of the disease was less clear. The gods were thought to mean only the best for the people of the land, and so the cause of a disease like cancer was as mysterious to the ancient Egyptians as the origin of evil and suffering is for religiously-minded people in the present.

The most common reasons for disease were thought to be sin, evil spirits, an angry ghost, or the will of the gods to teach someone an important lesson. Although the embalmers who dissected the bodies at death were aware of the internal organs and their relationship with each other spatially in the body's cavity, they did not share this information with doctors, and doctors did not consult with embalmers; the two professions were considered distinctly different with nothing of note to contribute to each other.

Doctors were aware that the heart was a pump and that veins and arteries supplied blood to the body, but they did not know how. They were aware of liver disease but not the function of the liver. The brain was considered a useless organ; all thought, feeling, one's character, was believed to come from the heart. A woman's uterus was believed to be a free-floating organ which could affect every other part of the body. Still, although their understanding of physiology was limited, Egyptian physicians seem to have been quite successful in treating their patients and were highly regarded by other cultures.

Medical Texts

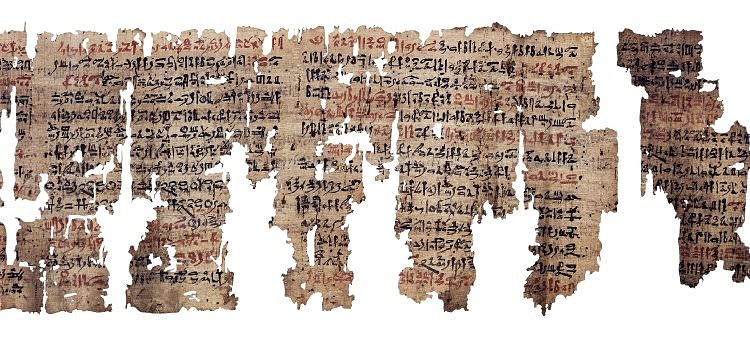

The medical texts of ancient Egypt were considered as effective and reliable in their time as any modern day equivalent. They were written by physicians for physicians and presented practical and magical cures and treatments. They were written on papyrus scrolls which were kept in the part of the temple known as the Per-Ankh ('House of Life'), but copies must have been carried by individual doctors who frequently made house calls.

These texts today are all known by the names of the individuals who discovered, purchased, or donated them to the museums where they are housed. The primary texts are:

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus (c. 1800 BCE) deals with conception and pregnancy issues as well as contraception.

The London Medical Papyrus (c. 1782-1570 BCE) offers prescriptions for issues related to the eyes, skin, burns, and pregnancy.

The Edwin Smith Papyrus (c. 1600 BCE) is the oldest work on surgical techniques.

The Ebers Papyrus (c. 1550 BCE) treats cancer, heart disease, diabetes, birth control, and depression.

The Berlin Medical Papyrus (also known as the Brugsch Papyrus, dated to the New Kingdom, c. 1570 - c. 1069 BCE) deals with contraception, fertility, and includes the earliest known pregnancy tests.

The Hearst Medical Papyrus (dated to the New Kingdom) treats urinary tract infections and digestive problems.

The Chester Beatty Medical Papyrus, dated c. 1200 BCE, prescribes treatment for anorectal diseases (problems associated with the anus and rectum) and prescribes cannabis for cancer patients (predating the mention of cannabis in Herodotus, long thought to be the earliest mention of the drug).

The Demotic Magical Papyrus of London and Leiden (c. 3rd century CE) is devoted entirely to magical spells and divination.

Each doctor had his or her own area of specialization and would consult the text corresponding to their field.

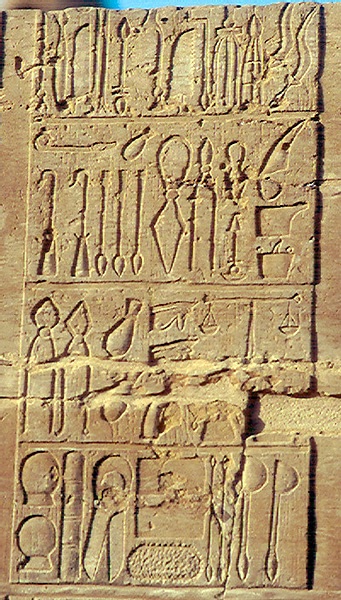

Medical Treatment

Doctors began their diagnosis and treatment of a patient by examining the person and coming to one of three conclusions:

1. I can treat this condition.

2. I can contend with this condition.

3. I can do nothing for this condition.

Cancer, for example, had no more a cure then than it does today. Heart disease could be contended with through spells, medicine, and a change in one's diet. Skin and eye problems could be treated through salves, spells, and incantations. Once the doctor had determined whether anything could be done, the next step was to understand the nature of the problem. It was a given that the root cause was some supernatural entity, but the physician had to understand how that entity was attacking the body and why. The patient would be asked a series of questions to determine what they were experiencing as well as what they might have done to deserve the affliction.

One example of this procedure, from the Ebers Papyrus, addresses the problem of a patient who presents with what appears to be a "mortal illness". The physician is instructed to examine the patient carefully, and if the body seems free of disease except for "the surface of the ribs," the doctor should then recite a spell against the disease and prescribe a mixture of bloodstone, red grain, and carob, cooked in oil and taken over the next four mornings with honey. The spell to be recited is not specified in this case but in many others is given.

Medicines were usually mixed with beer, wine, or honey, and each of these had their own medicinal properties. Beer was the most popular drink in ancient Egypt, frequently serving as one's wages, and was considered a gift from the gods for the people's health and enjoyment. Tenenet was the goddess of beer, but the drink was most frequently associated with Hathor (one of whose epithets was 'The Lady of Drunkenness'). Spells invoking Hathor appear in the medical texts, but an especially interesting one calls upon Set.

Although Set originally seems to have been a protective god, throughout most of Egypt's history, he was the arch-villain who murdered his brother Osiris and plunged the land into chaos. He does appear in certain eras, though, as a protector and champion, and his name is even taken by some kings (Seti I, for example) who especially honored him. In one spell, recited to cure an unnamed illness, Set is invoked to lend his power to the medicine prescribed: beer. Egyptologist Alison Roberts notes that "Set's influence in the beer drunk by the sick person is so great that tormenting demons become confused and are borne away, leaving the person restored to health" (98). The spell reads, in part:

There is no restraining Set. Let him carry out his desire to capture a heart in that name 'beer' of his - To confuse a heart, and to capture the heart of an enemy. (Roberts, 98)

Beer was thought to "gladden the heart" in general, but when one was ill, medicines mixed with beer - and combined with spells - were thought particularly effective. Beer and wine were also prescribed for children and nursing mothers. A prescription from the Ebers Papyrus for childhood incontinence calls for the mother to drink a cup of beer mixed with grass seeds and cyperus grass for four days while breastfeeding the child.

The Kahun Gynaecological Papyrus focuses primarily on the uterus as the source of a woman's ailments and frequently prescribes "fumigation of the womb" as a cure. This would be accomplished by directing incense smoke or inserting incense into the woman's vagina. Prescriptions frequently mention "discharges of the womb" as the primary cause for problems, as in this passage:

Examination of a woman aching in her rear, her front, and the calves of her thighs

You should say of it 'it is discharges of the womb'.

You should treat it with a measure of carob fruit, a measure of pellets, 1 hin of cow milk

Boil, cool, mix together, drink on 4 mornings. (Column I.8-12)

A test for fertility suggests placing an onion in a woman's vagina; if the scent of the onion was on her breath the next morning, she was considered fertile. Pregnancy tests are also addressed in which vegetation (specifically emmer and barley) is doused with a woman's urine; if the plants flourish, she is pregnant. It was also thought one could determine the sex of the child in this same way. If emmer seeds sprouted first, the child would be female; if the barley responded first, the child would be male. Contraceptives are also described in the text with one method cited as the insertion of a plug of crocodile dung into the vagina. Spells accompanying these procedures are also given to make them more effective.

The Demotic Magical Papyrus is completely devoted to spells, rituals, and incantations for summoning the gods and spirits for assistance, and some of these are thought to instruct the physician-magician on how to raise the dead. While this may be so, it seems the purpose of those spells was primarily to gain insight into the cause of death by summoning the spirit of the deceased. Spells are given to summon a drowned man or a murdered man, for example. To summon the spirit of the drowned man, the doctor should put a sea-carob stone (an object not yet identified) on the brazier and call out his name, while for the murdered man, one places the dung of an ass and an amulet of Nephthys on the brazier. To disperse spirits, the dung of an ape was placed on the fire.

Not all of the medical texts involved magical spells in the treatments, however. The Edwin Smith Papyrus, for the most part, gives straightforward procedures in treating injuries. Beginning with the head, the text goes down the body giving the type of injury sustained and suggesting how best to deal with the problem. Although eight magic spells appear on the back of the papyrus, the majority of the work is concerned entirely with medical procedures addressing injuries directly without an appeal for supernatural intervention.

Conclusion

The ancient Egyptians were acquainted with the concept that disease could be naturally occurring as early as the beginning of the Old Kingdom (c. 2613-2181 BCE). The architect Imhotep (c. 2667-2600 BCE), best known for his work on the king Djoser's Step Pyramid at Saqqara, had written medical treatises emphasizing this possibility and claiming that disease was not necessarily a punishment from the gods or the work of evil spirits. His ideas were not ignored either as he was highly respected for his work and was later deified as a god of medicine and healing.

Even so, lacking any other probable cause for sickness, the Egyptians continued to believe in supernatural elements influencing one's health. Although the title of swnw (general practitioner) and sau (magical practitioner) appear in inscriptions relating to doctors, magic was important for both. This is not surprising as human beings will always seek out a reason for any given experience. When faced with some seemingly inexplicable phenomenon, one will find a cause for it in that which seems most reasonable to one's belief system.

The earliest myths were told to explain the rising of the sun, the change of seasons, the reason for suffering; and these all had a supernatural element to them. The gods were present in every aspect of the ancient Egyptians' lives. When it came to determining the root cause of disease, therefore, they looked to that same source and implemented spells and rituals to call upon their gods for health and well-being with the same confidence people in the present day submit to any treatment prescribed by the modern medical profession.