Plato's Euthyphro is a Socratic dialogue on the concept of piety whose meaning and purpose continue to be debated. In reading the work only as a serious inquiry into the definition of an abstract concept, however, one is apt to miss the comical aspects of the piece that make it among the most entertaining of Plato's works.

The Dialogues of Plato have exerted such an extraordinary influence over Western thought and culture for the past 2,000 years that readers in the modern day frequently approach his works as philosophical icons. The Republic is routinely taught in college classes as the blueprint for the ideal society, the Apology is the epic defense of freedom of thought and personal integrity, the Symposium defines the true meaning of love, and all the other dialogues have been set and defined for their particular intellectual merit.

These interpretations are all accurate to greater or lesser degrees, but in reading Plato as Plato-the-Philosopher, one misses the nuances of Plato-the-Artist. Each of Plato's dialogues is a Greek drama with an introduction, rising action, dénouement, and conclusion. Republic can as easily be read as the proper way to order one's soul rather than how to construct an ideal city-state, but, further, it can be enjoyed simply as an account of a conversation at a friend's house party.

Any reader recognizes that, sometimes, one arrives at a party to find some undesirable nuisance there who is friend to the host but an irritation to everyone else, and so it is in Republic Book I when Socrates comes to Cephalus' house to find the sophist Thrasymachus there. Thrasymachus is instantly hostile to Socrates and his friends, insists on his own views as the only valid ones, and when proven wrong, refuses to admit it and chooses to leave instead. Thrasymachus is a fully realized character, all arrogance and bravado, easily recognized by any reader who has ever had to endure the pontifications and posturing of their own "Thrasymachus".

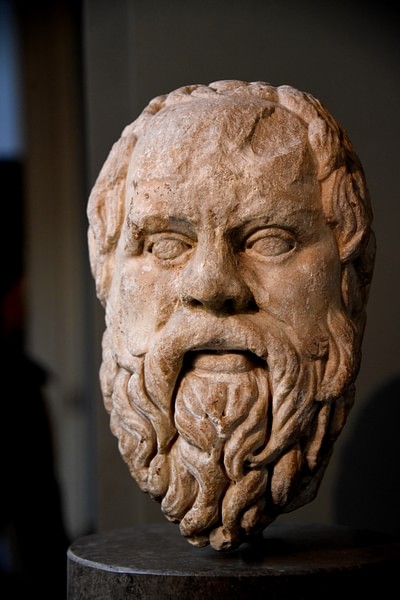

According to Diogenes Laertius (l. 3rd century CE), Plato's characters are so relatable and skillfully drawn because, before he was Plato the philosopher, he was a poet and playwright. Laertius' claims are frequently challenged because he failed to cite his sources, but in this case, his claim is supported by the literary artistry of the Platonic dialogues.

Plato's literary skills are apparent throughout all of his works, which offer a much more rewarding reading experience when approached as dynamic dramas instead of static philosophical discourses. Certainly, in many sections of each of the dialogues, one finds Socrates holding forth on some point while an interlocutor responds with one-word answers, but just as often, there is a discussion between two – or more – characters with distinct voices, phrasings, and levels of experience in life.

Even in those dialogues dealing with the most serious issues, such as the Phaedo with the concept of the immortality of the soul, there are light moments of humor, and in Symposium, all the way through, there are several comical passages. These moments all arise naturally from the characters and usually pass fairly quickly as the discussion moves on. In the dialogue of the Euthyphro, however, Plato begins on a serious note and then indulges himself freely throughout the rest of the piece as he openly mocks those who pretend to know what they do not. The Euthyphro is often overlooked and defined as a 'difficult dialogue' in that it never answers the central question it presents but, read as an ironic comedy, the piece succeeds completely.

Overview

Plato's Euthyphro is a dialogue between Socrates and the young, self-proclaimed 'prophet' Euthyphro outside the court in Athens just before Socrates is to go to trial in 399 BCE. Socrates is there to answer charges brought against him, while Euthyphro has arrived to bring a case against his father. As Socrates has been charged by the Athenians with impiety, and as Euthyphro claims to understand piety perfectly (5a), Socrates, sarcastically, asks the younger man to explain "what is piety and what is impiety?" Having at first stated that he can easily define piety as well as "many other stories about divine matters" (6c), it soon becomes clear that Euthyphro has no idea what piety is and no clear idea about "that accurate knowledge" (14b) of the will of the gods he boasts of repeatedly.

The importance of understanding the meaning of this concept of piety is impressed upon a reader in that Euthyphro is at court to prosecute a case against his own father for impiety. His father allowed a laborer who had killed a slave to die, bound in a ditch, while he awaited word from the authorities on how he should proceed against the man. Socrates, as noted, is there to defend himself against the same charge of impiety for "corrupting the youth" and "inventing new gods" (3b).

One of the men prosecuting Socrates, Meletus, is presented as being about the same age and having the same poor understanding of piety as Euthyphro does. In questioning the young man on the meaning of piety, Socrates is symbolically questioning his own accuser and, as always, challenging the complacency of accepting easy answers to complex problems by simply repeating traditional rhetoric instead of seeking honest responses for oneself through philosophical inquiry.

Piety in Ancient Greece

The concept under discussion, translated as "piety", was known as eusebia in ancient Greece. The word "piety" comes from the Latin pietas and means "dutiful conduct" while, today, "piety" is usually understood as "religious devotion and reverence to God" (American Heritage Dictionary), but in ancient Greece, eusebia meant neither of these exclusively and, at the same time, meant more.

Eusebia was the ideal that dictated how men and women interacted, how a master should speak to a slave and slave to master, how one addressed a seller in the marketplace as well as how one conducted one's self during religious festivals and celebrations. In short, eusebia was a social contract which maintained the established order and made clear one's position in the social hierarchy and what was considered proper behavior.

When Socrates is charged with impiety (dyssebia in Greek), however much a modern-day reader may object to the charge as unjust, in encouraging the youth of Athens to question their elders, Socrates would, in fact, have been guilty under the law. Young men were not supposed to question their elders, and yet Socrates' young students saw him repeatedly question their fathers and teachers and social superiors in the marketplace and were encouraged to do the same.

In the dialogue of the Euthyphro, in fact, a reader gets a firsthand view of Socrates "corrupting the youth" of Athens as he tries to lead the young man to the realization that what the gods want is not as easily grasped as conventional wisdom would have it. The question, "Do the gods love piety because it is pious, or is it pious because they love it?" (10a) is never fully answered because Euthyphro, mouthing traditional responses, cannot answer it.

Plato crafts the dialogue to impress on a reader how futile and self-defeating it finally is to simply rely on what one has been taught without ever questioning it. At the same time, he provides an audience with a front-row seat to the sort of exchange that would have enraged upper-class Athenians who may have felt victimized by Socrates' method of pursuing truth, and if read carefully, this exchange is quite funny.

Summary & Commentary

The dramatic situation is established immediately when Euthyphro greets Socrates outside of court and the two of them explain to each other why they are there: Socrates to answer charges and Euthyphro to press them (lines 2a-4e). When Socrates hears that Euthyphro is presuming to charge his father with impiety he says:

But before Zeus, do you, Euthyphro, suppose you have such precise knowledge about how the divine things are disposed, and the pious and impious things, that, assuming that those things were done just as you say, you don't fear that by pursuing a lawsuit against your father, you in turn may happen to be doing an impious act? (4e)

Euthyphro answers that he has no such fear because he knows “all such things precisely” (5a). Socrates (at this time over 70 years old) then ironically asks to become Euthyphro's student so that the younger man might teach him the underlying form and pattern of piety and impiety so that he will be better able to defend himself against the charges brought against him (5a-5b). Euthyphro gladly accepts, and when Socrates asks him to define the pious and impious, Euthyphro responds that it is simply what he himself is doing at the moment by prosecuting his father for impiety (5e).

Euthyphro backs up his statement by referencing stories of the gods and their behavior and how he is only emulating them, but Socrates points out that these stories depict the gods warring with each other and often behaving in quite impious ways and so Euthyphro's next definition that piety is "what is dear to the gods" (6e) makes no sense since some gods seem to value one thing while another something else. Scholars Thomas G. West and Grace Starry West comment:

[The gods' love of a concept] must be directed by that which really is good, noble, and just or else the meaning of human life must be dependent on the arbitrary will of mysterious beings who may not even be friendly to men and – given the multitude of willful authorities (the many gods) – the life of men and gods alike must be a tale of ignorant armies clashing by night on a darkling plain. Further, if the gods are guided by knowledge and do not give merely willful commandments, the guidance provided to men by divine law must be superfluous for one who is wise enough to discover for himself the truth of the good, noble, and just. The wise man has no need of gods. (13-14)

Euthyphro continues his clueless argument, claiming that what all the gods view as just and good is pious, but Socrates points out that he has already admitted that different gods have different values. He notes that human beings in court never deny what injustice is (say, murder) but, instead, claim they are not guilty of such an injustice (8c). In this same way, the gods do not deny that injustice exists but seem to differ on what kinds of acts are unjust.

Euthyphro, who earlier claimed he could tell Socrates all about the will of the gods and the operation of the universe and what true piety means, now tries to backtrack by claiming that what Socrates is asking of him is "no small work" (9b) – in other words, a proper answer might require more time than he has. He ventures another answer that piety is what all the gods love and impiety what all the gods hate (9e), but Socrates refutes this and asks "Is the pious loved by the gods because it is pious, or is it pious because it is loved?" (10a) to which Euthyphro has no real answer but continues to grope for one.

Throughout the dialogue, Socrates insults Euthyphro for his pretension – as in the line "you are no less younger than I am than you are wiser. But as I say, you are being fastidious [in answering me] because of your wealth of wisdom" (12a). Although Euthyphro has repeatedly boasted that he knows all about the gods and their will, when Socrates asks him about the many noble things that the gods produce as gifts to humanity, Euthyphro again complains how "to learn precisely how all these things are is a rather lengthy work" (14b). When Socrates suggests that perhaps what Euthyphro defines as piety is actually commerce in which people give worship to the gods and the gods give them gifts, Euthyphro agrees until this answer is also proven inadequate (14c-15c).

During this exchange, Socrates points out how Euthyphro has taught him nothing and their discussion has come full circle to the beginning (15c), which is precisely how Plato has constructed the dialogue. Modern-day readers often find the Euthyphro frustrating in that the same question is asked repeatedly and answered weakly, and yet, this is precisely Plato's design: a reader is made to feel Socrates' own frustration in trying to get a straight answer from a self-proclaimed expert on a subject that 'expert' actually knows nothing about.

When Socrates suggests they start all over and begin again to try to define piety and impiety, Euthyphro says, "Some other time, then, Socrates. For now I am in a hurry to go somewhere, and it is time for me to go away" (15e). Socrates has the last lines of the dialogue, which should be read sarcastically, as he cries out after the fleeing Euthyphro:

By leaving you are throwing me down from a great hope I had: that by learning from you the things pious and the things not, I would be released from Meletus' indictment. For I hoped to show him that I have now become wise in the divine things from Euthyphro, and that I am no longer acting unadvisedly because of ignorance or making innovations concerning them and especially that I would live better for the rest of my life. (15e-16a)

The humor of the piece is more apparent if read aloud with inflection and, especially, if one understands the basic concepts under consideration and the social structure the dialogue relies on. Even without this, though, any reader would appreciate the absurdity of pursuing a legal case against one's father when one does not even understand the precepts concerning that case, and, viscerally, one feels the frustration of trying to converse intelligently with someone who not only claims to know what they do not but acts willfully from a position of ignorance.

Conclusion

In the Euthyphro, a careful reader will appreciate the talent of Plato as comic dramatist. While initially boasting that he knows everything about piety, it becomes clear, after four different definitions of the concept are introduced and refuted, that Euthyphro knows nothing of piety other than the conventional definition he has been taught by others, most notably the very father he is now prosecuting for impiety.

The father of the household was lord (kyrios) and had the responsibility of teaching his sons the importance of eusebia, among other things. That Euthyphro should prosecute his own father for impiety, without fully understanding the concept he is allegedly defending, would not succeed so well as comedy if Plato did not draw the character so carefully and so accurately. Further, Plato chooses the name purposefully for comic effect in that the name Euthyphro means "straight thought" and the character demonstrates the exact opposite through the twists and turns of his convoluted argument.

Just as the figure of Thrasymachus is familiar, a reader recognizes having known a "Euthyphro" at one point or another: the sort of person who speaks loudly and with confidence on matters he or she does not know and, often, matters no one can possibly know. That Euthyphro's pretension is so profoundly annoying throughout the dialogue is testament to Plato's skill as a writer; in this dialogue, one meets a young man one already knows, has known, or will know who refuses to admit he does not know what he is talking about even when all evidence makes that clear.

Plato's Euthyphro is a potent, and absurdly comic, warning against the pretension of speaking – and acting – on subjects one knows nothing about. The work is also easily among the best examples of dramatic comedy from beginning to end in its subtle presentation, characterization, and timing. Plato recognizes when it will work best for Socrates to take a shot at Euthyphro directly or when a more subtle dig will serve.

Socrates' allusions to the tales of the gods all make clear he knows more about Greek religion than Euthyphro, even though the younger man insists upon his superior knowledge. It is a final testament to Plato's skill that, at the conclusion when Euthyphro leaves, the reader feels the same sense of relief as Socrates.