The interiors of Roman buildings of all description were very frequently sumptuously decorated using bold colours and designs. Wall paintings, fresco and the use of stucco to create relief effects were all commonly used by the 1st century BCE in public buildings, private homes, temples, tombs and even military structures across the Roman world. Designs could range from intricate realistic detail to highly impressionistic renderings which frequently covered all of the available wall space including the ceiling. Subjects could include portraits, scenes from mythology, architecture using trompe-l'oeil, flora, fauna and even entire gardens, landscapes and townscapes to create spectacular 360° panoramas which transported the viewer from the confines of a small room to the limitless world of the painter's imagination.

Materials & Techniques

Wall paintings were created using a painstaking build up of various layers of material. The optimum process is described by both Vitruvius and Pliny the Elder. First, a rough coat of mortar is applied to the surface, sometimes three layers thick and composed of lime and sand (or volcanic pozzolana). Next, a further three coats were added, this time using a mixture of lime and fine crushed marble to give a smoother finish and then glass, marble and cloth were used to polish the surface and prepare it for painting. Colours were added when the surface was still wet (fresco) but details might also be added to a dried surface (tempera). If the surface were wood then colours might be first dissolved in wax and added to the wall using a spatula.

Designs

Roman wall painters (or perhaps their clients) preferred natural earth colours such as darker shades of reds, yellows and browns. Blue and black pigments were also popular for plainer designs but evidence from a Pompeii paint shop illustrates that a wide range of colour shades was available. All kinds of scenes were painted on walls which were often sketched in outline first using red ochre. Initially influenced by Hellenistic artists, scenes from Greek mythology were particularly popular and especially those involving Dionysos. Other popular subjects included gladiator contests, landscapes, buildings, gardens and still-lifes. Decorative motifs appear again and again, for example, tripods, fruit, foliage, ribbons, candelabra, theatre masks and architectural elements such as columns.

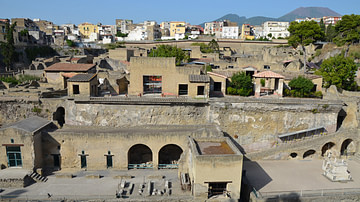

The wealth of surviving examples at sites such as Pompeii and Herculaneum has allowed Roman wall painting to be classified into four different styles. In Style I, which became popular from the early 2nd century BCE, the wall was typically painted with a dado, a middle space often divided into three areas and a frieze and cornice as in Classical architecture. Stucco was used to give a three-dimensional effect to certain points of the decoration, in particular the cornice. An example of the style can be found in the Samnite House at Herculaneum.

Style II originated in Rome around 90 BCE and incorporated painted columns, often with an architrave and pediment acting as a frame to inner scenes, which themselves can be framed by columns. The paintings are given perspective and religious and cult scenes are particularly popular. Another feature of the style is the depiction of small framed paintings either side of the larger, more striking central scene. The House of Livia on the Palatine hill in Rome has excellent examples of this style.

In Style III, which appeared in the reign of Augustus, the architectural elements become more fantastic and are elaborately decorative. The dominance of black, red and yellow continues but greens and blues appear and more wall space is left plain. There is also a greater attention paid to symmetry rather than perspective. A fine example is the House of Lucretius Fronto at Pompeii.

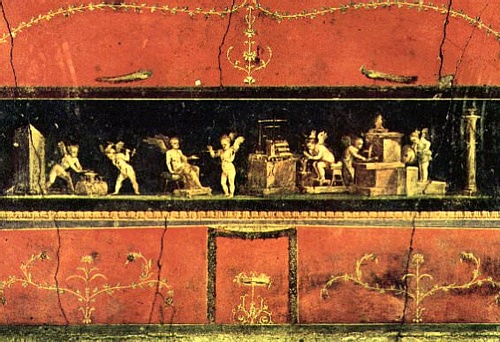

The highly decorative Style IV is best seen at Pompeii where many of the villas were redecorated in the style following the earthquake of 62 CE. The House of the Vetti displays the characteristics of this style with large central panels; there is an increasing use of white for backgrounds, a greater attention to detail and perspective returns in the paintings which include more intricate decorative motifs, floral borders and friezes between panels.

Later developments in wall painting are more difficult to trace due to a lack of surviving examples and a general preference in later times for marble veneers and tempera painting which survives less well than true fresco. Elements of Style III and IV seem to continue but there is less use of the dado and the three-way division of walls is largely abandoned to allow for larger-scale single scenes which present larger-than-life figures. By the 3rd century CE one of the best sources of wall painting comes from Christian catacombs where scenes from both the Old and New Testament were popular such as Daniel in the lion's den, Jonah and the Whale and Christ's miracles. There was also a trend for dividing the wall and ceiling using stripes and lines against a white background.

Outstanding Examples

The triclinium or dining room from the 1st century BCE residence known as Livia's Villa (wife of Augustus) in Rome has a 360° panorama of an impressionistically rendered garden which runs around the room completely ignoring the corners. The impressive variety and luxuriance in the garden includes plants, flowers, fruit, laurel and palm trees, vines, birds and insects, all life-size and painted against a brilliant blue sky. Depth and perspective are cleverly achieved by rendering the subjects in finer detail the closer they are to the viewer whilst the background subjects are painted less distinctly. A low cane and wicker fence in the foreground completes the illusion that one is in a garden paradise rather than in a small claustrophobic room with no windows.

The triclinium of the 1st century CE private villa known as the House of the Vetti in Pompeii has some of the most famous images from Roman wall painting. The rich red walls are divided by black bands and the frieze running above the dado depicts cupids and psychai involved in all kinds of activities such as religious rites, shooting arrows, racing in antelope-drawn chariots, selling flowers and perfumes and even working as goldsmiths, vintners and bakers. The whole run of scenes then culminates in a procession honouring Dionysos with goat-drawn wagons and the pastoral god Pan.

Conclusion

Roman wall painting, then, has provided us with a rare glimpse of the artistic tastes and preferences of the Romans and the delicate frescoes which have miraculously survived the ravages of time allow us to not only see for ourselves the religious and cultural practices, the architecture, the industries, even the food of the Roman world but they also allow us to gaze at and admire the very same views that were likewise enjoyed by a people separated from us in time by twenty centuries.