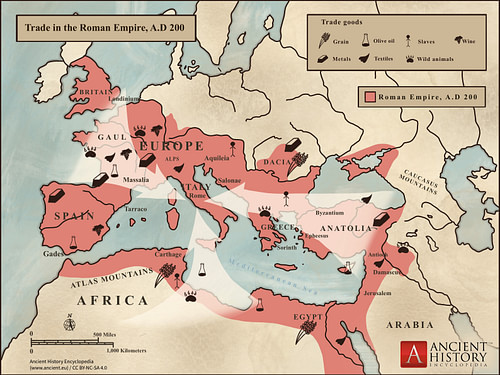

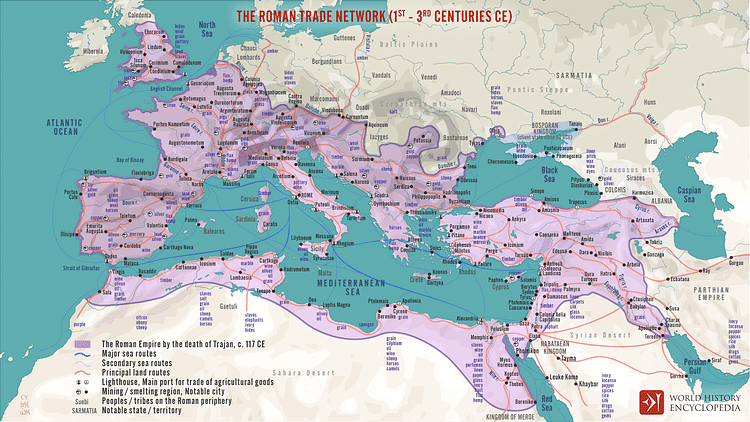

Regional, inter-regional and international trade was a common feature of the Roman world. A mix of state control and a free market approach ensured goods produced in one location could be exported far and wide. Cereals, wine and olive oil, in particular, were exported in huge quantities whilst in the other direction came significant imports of precious metals, marble, and spices.

Factors Driving Trade

Generally speaking, as with earlier and contemporary civilizations, the Romans gradually developed a more sophisticated economy following the creation of an agricultural surplus, population movement and urban growth, territorial expansion, technology innovation, taxation, the spread of coinage, and not insignificantly, the need to feed the great city of Rome itself and supply its huge army wherever it might be on campaign.

The economy in the Roman world displayed features of both underdevelopment and high achievement. Elements of the former, some historians have argued (notably M.I.Finley), are:

- an over-dependence on agriculture

- a slow diffusion of technology

- the high level of local town consumption rather than regional trade

- a low level of investment in industry.

However, there is also evidence that from the 2nd century BCE to the 2nd century CE there was a significant rise in the proportion of workers involved in the production and services industries and greater trade between regions in essential commodities and manufactured goods. In the later empire period, although trade in the east increased - stimulated by the founding of Constantinople - trade in the western empire declined.

The Roman attitude to trade was somewhat negative, at least from the higher classes. Land ownership and agriculture were highly regarded as a source of wealth and status but commerce and manufacturing were seen as a less noble pursuit for the well-off. However, those rich enough to invest often overcame their scruples and employed slaves, freedmen, and agents (negotiatores) to manage their business affairs and reap the often vast rewards of commercial activity.

Traded Goods

Whilst the archaeological evidence of trade can sometimes be patchy and misrepresentative, a combination of literary sources, coinage and such unique records as shipwrecks helps to create a clearer picture of just what the Romans traded, in what quantity, and where.

Trade involved foodstuffs (e.g. olives, fish, meat, cereals, salt, prepared foods such as fish sauce, olive oil, wine and beer), animal products (e.g. leather and hides), objects made from wood, glass, or metals, textiles, pottery, and materials for manufacturing and construction such as glass, marble, wood, wool, bricks, gold, silver, copper, and tin. Finally, there was, of course, also the substantial trade in slaves.

The fact that many goods were produced as regional specialities on often very large estates, for example, wine from Egypt or olive oil from southern Spain, only increased the inter-regional trade of goods. That such large estates could producea massive surplus for trade is evidenced at archaeological sites across the empire: wine producers in southern France with cellars capable of storing 100,000 litres, an olive oil factory in Libya with 17 presses capable of producing 100,000 litres a year, or gold mines in Spain producing 9,000 kilos of gold a year. Although towns were generally centres of consumption rather than production, there were exceptions where workshops could produce impressive quantities of goods. These 'factories' might have been limited to a maximum workforce of 30 but they were often collected together in extensive industrial zones in the larger cities and harbours, and in the case of ceramics, also in rural areas close to essential raw materials (clay and wood for the kilns).

Goods were not only exchanged across the Roman world, however, as bustling ports such as Gades, Ostia, Puteoli, Alexandria, and Antioch also imported goods from such far-flung places as Arabia, India, Southeast Asia, and China. Sometimes these goods followed land routes such as the well-established Silk Road or travelled by sea across the Indian Ocean. Such international trade was not necessarily limited to luxury goods such as pepper, spices (e.g. cloves, ginger, and cinnamon), coloured marble, silk, perfumes, and ivory, though, as the low-quality pottery found in shipwrecks and geographical spread of terracotta oil lamps illustrates.

Transporting Goods

Goods were transported across the Roman world but there were limitations caused by a lack of land transport innovation. The Romans are celebrated for their roads but in fact, it remained much cheaper to transport goods by sea rather than by river or land as the cost ratio was approximately 1:5:28. Nevertheless, it should be remembered that sometimes the means of transport was determined by circumstances and not by choice and all three modes of transport grew significantly in the 1st and 2nd centuries CE.

Although transport by sea was the cheapest and fastest method (1,000 nautical miles in 9 days) it could also be the riskiest - subject to the whims of weather and theft from piracy - and was restricted by the seasons as the period between November and March (at least) was regarded as being too unpredictable for safe passage.

From the analysis of over 900 shipwrecks from the Roman period the most typical size of merchant vessel had a capacity for 75 tons of goods or 1500 amphorae but there were bigger vessels capable of transporting up to 300 tons of goods. One interesting example is the 40s CE Port Vendres II wreck located in the Mediterranean off the Spanish-French border. The cargo was taken from at least 11 different merchants and contained olive oil, sweet wine, fish sauce, fine pottery, glass, and ingots of tin, copper, and lead.

State Control of Trade

In the imperial period, there was great state control over trade in order to guarantee supply (the annona system) and even a state merchant fleet, replacing the system during the Republic of paying subsidies (vecturae) to encourage private shipowners. There was a specific official in charge of the grain supply (the praefectus annonae) who regulated the various shipowner associations (collegia navicularii). The state taxed the movement of goods between provinces and also controlled many local markets (nundinae) - often held once a week - as the establishment of a market by a large land-owner had to be approved by the Senate or emperor.

The greatest state expenditure was on the army, which required some 70% of the budget. The state's apparatus of taxation to acquire revenue may be considered a success in that, despite the tax burden, local prosperity and economic growth were not unduly hampered.

Evidence of state control can be seen in the many goods which were stamped or carried markers indicating their origin or manufacturer and in some cases guaranteeing their weight, purity or genuineness. Pottery, amphorae, bricks, glass, metal ingots (important for coinage), tiles, marble and wooden barrels were usually stamped and general goods for transportation carried metal tags or lead seals. These measures helped to control trade, provide product guarantees and prevent fraud. Inscriptions on olive oil amphorae were particularly detailed as they indicated the weight of the vessel empty and of the oil added, the place of production, the name of the merchant transporting them and the names and signatures of the officials who carried out these controls.

Trade was also carried out completely independent from the state, though, and was favoured by the development of banking. Although banking and money-lending generally remained a local affair there are records of merchants taking out a loan in one port and paying it off in another once the goods were delivered and sold on. There is also abundant evidence of a free-trade economy beyond the reaches of the empire and independent of the larger cities and army camps.

Conclusion

Whatever the exact economic mechanisms and proportion of state to private enterprise, the scale of trade in the Roman world is hugely impressive and no other pre-industrial society came even close. Such mundane functional items as amphorae or oil lamps were produced in their millions and it has been estimated that in Rome alone the quantity of oil traded was 23,000,000 kilograms per year whilst the city's annual wine consumption was well over 1,000,000 hectolitres, probably nearer 2 million. These kinds of figures would not be seen again until industrialisation swept the developed world long after Roman traders had closed their accounting books and been forgotten by history.