Roman artillery weapons were instrumental in the successes of the Roman army over centuries and were especially used in siege warfare, both for offence and defence. Principally used in fixed positions or onboard ships, these machines, known generally as ballistae, could fire bolts or heavy stones over several hundred metres to punch holes in enemy fortifications, batter ships, and cause devastation in the ranks of opposing troops.

The Ballista - Origins, Developments & Use

The Romans continuously improved upon the torsion weapons that had first appeared in 4th century BCE Greece. The two main types were the katapeltēs oxybelēs which fired bolts and the lithobolos which fired stones, both over distances of over 300 metres (as demonstrated in modern full-size reproductions). The Romans evolved these into more efficient machines with greater stability, more mobility, and better materials and design tweaks to achieve ever greater range and accuracy. However, non-torsion catapults were never completely replaced and remained a useful addition to the Romans' formidable array of weaponry.

Artillery weapons which fired bolts or stones (or both) were used to keep defenders off the ramparts whilst rams were used, siege ramps were constructed or towers moved into position to break down the defenders' fortifications. Heavier missiles might also break down defensive walls and allow troops to overrun the city. Ballistae could also be used more imaginatively, for example, placed on the upper floors of siege towers or on the decks of ships. Even so, as these machines were so heavy and their rate of fire relatively slow, they were mainly used as fixed emplacement weapons and not as mobile weapons in field engagements. Arranged in batteries, when possible on high ground, they could, though, provide a devastating volley of fire on enemy positions and must have presented an ominous sight when they were trundled within range of the defenders' positions.

The Carroballista, Scorpio & Cheiroballistra

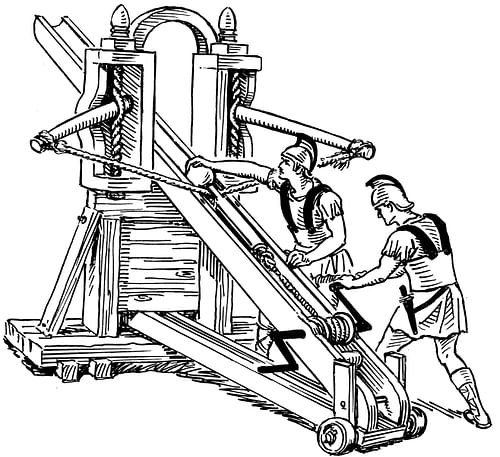

Roman torsion catapult (catapulta) devices typically looked like a cross-bow in design and had a wooden or, even better, metal frame (capitulum) consisting of a stock, winch and base. Two coils of rope (nervi torti) made from hair or better, animal sinew and encased in a metal-plated box under tension, acted as springs which, when released, gave the arm (bracchia) of the device its power of propulsion. There were many different versions of ballistae and the tension in the rope might also be achieved by turning hand-spikes, windlasses, pulleys or cogs. Technical manuals with calibrating formulae and tables of standard measurements for the various pieces which made up torsion catapults first appeared in c. 270 BCE and indicate that warfare had become a science where technological advancements often brought victory.

As technologies improved, by the beginning of the 2nd century CE artillery did become increasingly mobile, adding a new and lethal dimension to ancient warfare. Trajan's Column in Rome provides relief sculptures showing cart-mounted carroballista bolt-firing weapons. These were an improvement on older catapults as their spring mechanisms were set wider apart giving the weapon greater firing accuracy. In addition, the all iron frame not only made the whole apparatus lighter and more mobile but allowed the arm to be pulled back even further, giving 25% more power. Vegetius states that each legion was equipped with 55 carroballista and, indeed, every legion had its own dedicated specialists in artillery who not only fired the weapons but also made, repaired and improved them.

The scorpio was a smaller version ballista operated by one man that appeared around the 1st century BCE. (Although confusingly, some later Roman writers would use the term scorpio to refer to large single-armed catapults too). Its smaller size, metal head, and concave arms gave it greater accuracy and power so that in skilled hands it could fire metal bolts with enough force to rip through two enemy soldiers at once. During the 1st century CE another innovation was the cheiroballistra. Also small enough to be operated by a single shooter, the weapon was constructed almost entirely in metal, including the arms, making it more resistant to weather and accurate enough that a sight arch could be added between the two copper-encased springs.

The 'Wild Ass'

Stone-throwing devices came in various calibres firing stones from as small as 0.5 kg to as large as 25 kg (as used in the 70 CE siege of Jerusalem). Vitruvius mentions even larger grades of stones, the heaviest being a massive 163 kg. Besides stones there are also records of incendiary missiles being used in Roman warfare, for example, at the siege of Masada in 73-4 CE. The stone-throwers took two forms - either like the arrow-firing apparatus or large one-armed catapults, known in the 4th century CE as the onager or 'Wild Ass' because of its terrific recoil but, in fact, first appearing in the 2nd century CE. Easier to build than the more complex two-armed ballista they were also less accurate and required a crew of eight and a specially built base of brick or earth to achieve some kind of stability when the device was fired and an 80 kg stone launched from its basket. Vegetius claims ten such weapons were assigned to each legion. These more primitive weapons were indicative of the general decline in torsion artillery in the later empire and it would be many centuries until the field of battle once more saw artillery with the sophistication and accuracy that the Romans had been able to field.