The Nazca civilization flourished in southern Peru between 200 BCE and 600 CE and amongst their most famous legacies are the geoglyphs and lines - often referred to as Nazca Lines - along the eastern coast of Peru and northern Chile. The designs are stylized drawings of animals, plants and humans or simple lines connecting sacred sites or pointing to water sources.

The Nazca lines, drawn across deserts and hills, were made over many centuries and although their exact purpose is disputed, the most widely held theory is that they were designed to be walked along as part of religious rites and processions. The Nazca lines are listed by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site.

Designs & Dimensions

The lines were made remarkably easily and quickly by removing the oxidised darker surface rocks which lay closely scattered across the lighter coloured desert pampa floor. The aridity of the desert has preserved them well (although the sun can darken the exposed lighter sand over time) and many can still be clearly seen today. Most designs are only visible from the air but some were made on hillsides and so are visible from the ground.

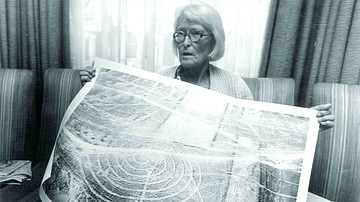

Lines could be single - both straight and curved - or in groups and could cross each other in complicated networks. The width and length of lines could vary, one of the longest straight lines is 20 km long and the total combined length of Nazca lines has been estimated at over 1,300 km. Those lines used to describe a specific shape are generally composed of a single continuous line. Designs could be geometric shapes such as triangles, spirals, trapezoids, arrows and zig-zags. Examples of animal designs are a hummingbird, condor, monkey, llama, duck, lizard, spider and even a killer whale. Trees, plants and flowers such as the cactus were another subject, human figures were also drawn (especially on hillsides), as were objects such as tripods, looms and fans. There are also many forms as yet unidentified. The scale of the designs can be huge, many are at least the size of a sports field.

The creation of such large designs is made possible by carefully increasing the proportions taken from a small scale model. In total, more than 300 examples of geometric, animal and human figures have been identified which, along with purposely cleared areas, collectively cover over 640 square kilometres of desert.

Purpose

The exact purpose of the lines is much debated amongst scholars and the general public. Proposals range from astronomical maps relevant to the agricultural calendar to indicators of sacred routes between Nazca religious sites, a common device in other ancient South American cultures. Those on hillsides may have been intended as direction finders for travellers - which is almost certainly what they did become, intentionally or not. The lines which create shapes never cross each other and usually have a different starting and ending point indicating that they may have been paths walked during religious ceremonies as part of a repeated ritual. One such line actually leads directly from a small hut. More fanciful suggestions have the lines as the work of visitors from another world but these are usually dismissed for the complete lack of evidence and the ease with which the designs can be created - one experiment illustrated that a small team could clear 16,000 square metres of desert in a week.

Perhaps the most obvious purpose of the lines is that the Nazca wanted to display their reverence for the natural world and pay homage to their gods, especially those who controlled the weather, so vital to successful agriculture in the arid plains of Peru. In support of this view is the fact that many of the designs also appear on Nazca textiles and pottery decoration. In addition, many of the straight lines radiate from hills and mountains and other water sources (62 such points have been identified), trapezoid shapes often 'point' in the direction of a water source, and the two principal Nazca sites of Ventilla and Cahuachi were connected by such a line.

Conclusion

Perhaps, the true purpose of the Nazca lines was a combination of some of the suggestions mentioned above. It is a fact that the lines appear in greater number closer to settlements and river courses and that they were made over several centuries. They can easily be made by a single individual in a few days and very often newer designs overlap and ignore older ones which would strongly suggest a lack of long-term and unified planning and, therefore, that they were made by different groups at different times and served more than a single purpose.