The stone head sculptures of the Olmec civilization of the Gulf Coast of Mexico (1200 BCE - 400 BCE) are amongst the most mysterious and debated artefacts from the ancient world. The most agreed upon theory is that, because of their unique physical features and the difficulty and cost involved in their creation, they represent Olmec rulers.

Seventeen heads have been discovered to date, 10 of which are from San Lorenzo and 4 from La Venta; two of the most important Olmec centres. The heads were each carved from a single basalt boulder which in some cases were transported 100 km or more to their final destination, presumably using huge balsa river rafts wherever possible and log rollers on land. The principal source of this heavy stone was Cerro Cintepec in the Tuxtla Mountains. The heads can be nearly 3 m high, 4.5 metres (9.8 feet, 14.7 feet) in circumference and average around 8 tons in weight. The heads were sculpted using hard hand-held stones and it is likely that they were originally painted using bright colours. The fact that these giant sculptures depict only the head may be explained by the widely held belief in Mesoamerican culture that it was the head alone which contained the emotions, experience, and soul of an individual.

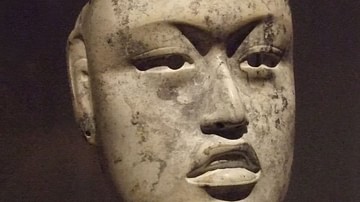

Facial details were drilled into the stone (using reeds and wet sand) so that prominent features such as the eyes, mouth, and nostrils have real depth. Some also have deliberately drilled dimples on the cheeks, chin, and lips. The heads all display unique facial features - often in a very naturalistic and expressive manner - so that they may be considered portraits of actual rulers. The scholar M.E. Miller identifies Colossal Head 5, for example, as a second-millenium BCE ruler of San Lorenzo. Although the physionomy of the sculptures has given rise to unfounded speculation of contact with civilizations from Africa, in fact, the physical features common to the heads are still seen today in residents of the modern Mexican cities of Tabasco and Veracruz.

The subject often wears a protective helmet which was worn by the Olmec in battle and during the Mesoamerican ballgame. These can vary in design and pattern and sometimes the subject also has jaguar paws hanging over the forehead, perhaps representing a jaguar pelt worn as a symbol of political and religious power, a common association in many Mesoamerican cultures. Colossal Head 1 from La Venta, instead, has huge talons carved on the front of the helmet.

Some heads are also recarvings of other objects. For example, San Lorenzo Colossal Head 7 was originally a throne and has a deep indentation on one side and Altar 5 from La Venta seems to have been abandoned in the middle of such a conversion. Miller suggests that perhaps a specific ruler's throne was converted into a colossal portrait in an act of remembrance following that ruler's death.

Many of the stones are difficult to place in their original context as they were not necessarily found in the positions the Olmecs had originally put them. Indeed, Almere Read (41) suggests that even the Olmecs themselves regularly moved the heads around for different ritual purposes. Another theory is that the heads were used as powerful markers of rulership and distributed to declare political dominance in various territories. Interestingly, the four heads from La Venta were perhaps originally positioned with such a purpose in mind so that they stood as guardians to the sacred precinct of the city. Three were positioned at the northern end of the complex and the other one stood at the southern end; but all faced outwards as if protecting the precinct. These heads are very similar to the San Lorenzo heads but display a regional variance in that they are wider and more squat in appearance.

That the other heads might have been discovered out of their original setting is suggested by the fact that very often they show signs of deliberate vandalism and most were buried sometime before 900 BCE in what appears to have been a purposeful ritual distancing with the past. However, it has also been suggested that some of the heads were buried shortly after their production in a process of ancestor worship or that they were defaced and buried by subsequent rulers to legitimize their claim to power and exclude competing lineages. It could also be that they were even damaged in order to neutralize the dead ruler's power. Whatever the reason, the heads were buried and forgotten for nearly three thousand years until the first head was re-discovered, in 1871 CE, with the last being excavated as recently as 1994 CE.