Unlike the rich corpus of ancient Egyptian funerary texts, no such “guidebooks” from Mesopotamia detail the afterlife and the soul's fate after death. Instead, ancient Mesopotamian views of the afterlife must be pieced together from a variety of sources across different genres.

Many literary texts, most famously the Epic of Gilgamesh, contemplate the meaning of death, recount the fate of the dead in the netherworld, and describe mourning rites. Other texts were probably composed in order to be recited during religious rites involving ghosts or dying gods. Of these ritual texts, the most notable are Gilgamesh, Enkidu and the Netherworld; Ishtar's Descent to the Netherworld; and Nergal and Ereshkigal. Further sources for Mesopotamian afterlife beliefs include burials, grave inscriptions, economic texts recording disbursements for funerals or cults of the dead, references to death in royal inscriptions and edicts, chronicles, royal and private letters, lexical texts, cultic commentaries, magico-medical texts, omens, and curse formulas.

In addition to belonging to different genres, the sources for Mesopotamian beliefs in the afterlife come from distinct periods in Mesopotamian history and encompass Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, and Assyrian cultures. We should therefore be careful not to view Mesopotamian afterlife beliefs as static or uniform. Like all cultural systems, Mesopotamian ideas of the afterlife transformed throughout time. Beliefs and practices relating to the afterlife also varied with socio-economic status and differed within official and popular religious paradigms. With this in mind, however, cultural continuity between the Sumerian civilization and its successors allows a synthesis of diverse sources in order to provide a working introduction to Mesopotamian concepts of the afterlife.

The Netherworld

Ancient Mesopotamians conceptualized the netherworld as the cosmic opposite of the heavens and as a shadowy version of life on earth. Metaphysically, it was thought to lie a great distance from the realm of the living. Physically, however, it lay underground and is poetically described as located only a short distance from the earth's surface.

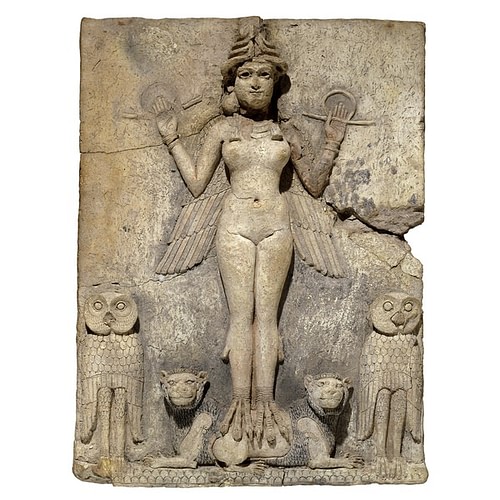

Literary accounts of the netherworld are generally dismal. It is described as a dark “land of no return” and the “house which none leaves who enters,” with dust on its door and bolt (Dalley 155). Yet other accounts moderate this bleak picture. For instance, a Sumerian work referred to as the Death of Urnamma describes the spirits of the dead rejoicing and feasting upon the ruler Urnamma's arrival in the netherworld. Shamash, the sun god of justice, also visited the netherworld every night on his daily circuit through the cosmos. Similarly, scholar Caitlín Barrett has proposed that grave iconography – specifically symbolism related to the goddess Inanna/Ishtar who descended and returned from the underworld — indicates a belief in a more desirable afterlife existence than the one described in many literary texts. Although humans could not hope to return to life in exact imitation of Inanna/Ishtar, Barrett argues, by utilizing funerary iconography representing Ishtar, they could seek to avoid the unpleasant aspects of the netherworld from which Inanna/Ishtar herself had escaped. The Mesopotamian netherworld is therefore best understood as neither a place of great misery nor great joy, but as a dulled version of life on earth.

One of the most vivid portrayals of the netherworld describes a subterranean “great city” (Sumerian "iri.gal") protected by seven walls and gates where the spirits of the dead dwell. In the Akkadian Descent of Ishtar to the Underworld, Ishtar passes through these seven gates on her journey to the netherworld. At each gate she is stripped of her garments and jewelry until she enters the city of the dead naked. In light of such descriptions, it is perhaps notable that Mesopotamian funerary rites for the elite could last up to seven days.

The community of spirits living in the “great city” was sometimes called Arallu in Akkadian or Ganzer in Sumerian, terms of uncertain meaning. Sumerian Ganzer is also a name for the underworld and an entrance to the underworld. Paralleling the Mesopotamian idea of divine authority in heaven and earth, the realm of the dead was governed by particular deities who were ranked in hierarchical order with a supreme chief at their head. In older texts the goddess Ereshkigal (“Mistress of the Great Earth”) was queen of the Netherworld. She was later replaced by the male warrior god Nergal (“Chief of the Great City”). An Akkadian myth dating at latest to the mid-second millennium BCE attempts to resolve the conflicting traditions by making Ereshkigal the spouse of Nergal. Like the deities in heaven who met regularly in a divine council to render judgments for the universe, the divine rulers of the underworld were assisted in their decisions by an elite body of divinities called the Anunnaki.

It must be emphasized that the Mesopotamian netherworld was not a “hell.” Although it was understood as the geographic opposite of the heavens, and although its environment was largely an inversion of heavenly realms (for instance, it was characterized by darkness instead of light), it did not stand opposite heaven as a possible dwelling place for dead spirits based on behavior during life. The Mesopotamian netherworld was neither a place of punishment nor reward. Rather, it was the only otherworldly destination for dead spirits whose bodies and graves or cult statues had received proper ritual care.

Human Nature & Fate after Death

In the Old Babylonian Atrahasis epic, the gods created humans by mixing clay with the blood of a rebellious deity named We-ilu who was specially slaughtered for the occasion. Humans therefore contained both an earthly and a divine component. Yet the divine element did not mean that humans were immortal. The Mesopotamians had no concept of either physical resurrection or metempsychosis.[4] Rather, Enki (Akkadian Ea), the Sumerian deity of wisdom and magic, ordained death for humans from their very inception. Mortality defined the fundamental human condition, and is even described as the destiny (Akk. šimtu) of mankind. The most common euphemism for dying in Mesopotamian texts is “to go to one's fate” (Cooper 21). The quest for physical immortality, suggests the Epic of Gilgamesh, was consequently futile. The best humans could strive for was enduring fame through their deeds and accomplishments on earth. Immortality, insofar as it was metaphorically possible, was actualized in the memory of future generations.

Humans were considered alive (Akk. awilu) as long as they had blood in their veins and breath in their nostrils. At the moment when humans were emptied of blood or exhaled their last breath, their bodies were considered empty cadavers (Akk. pagaru. The condition of this empty corpse is compared to deep sleep and, upon burial in the ground, the body fashioned from clay “returned to clay” (Bottéro, “Religion” 107). The biblical euphemism for death as sleep (New Revised Standard Version, 1 Kgs. 2:10; 2 Kgs. 10:35; 15:38; 24:6; 2 Chron. 9:31) and the statement, “You are dust, and to dust you shall return” (Gen. 3:19; cf. Ecc. 3:20), point to the common cultural milieu underlying ancient Mesopotamian and Israelite paradigms.

The Mesopotamians did not view physical death as the ultimate end of life. The dead continued an animated existence in the form of a spirit, designated by the Sumerian term gidim and its Akkadian equivalent, eṭemmu. The eṭemmu is best understood as a ghost. Its etiology is described in the Old Babylonian Atrahasis epic I 206-230, which recounts the creation of humans from the blood of the slain god We-ilu. The text uses word play to connect the etemmu to a divine quality: We-ilu is characterized as one who has ṭemu, “understanding” or “intelligence”. Thus, humans were thought to be composed of a corporeal body and some type of divine insight.

It must be stressed that Mesopotamian notions of the physical body and the eṭemmu do not represent a strict body/soul dualism. Unlike the concept of psyche in Classical Greek thought, the eṭemmu was closely associated with the physical corpse. Some texts even speak of the eṭemmu as if it were identical to the body. For instance, the eṭemmu is sometimes described as “sleeping” in the grave (Scurlock, “Death” 1892) – a description that echoes accounts of the corpse or pagaru. Further, the eṭemmu retained corporeal needs such as hunger and thirst, a characteristic that will be discussed in more detail below. It also unclear whether the eṭemmu existed within the living body prior to death (and was thus an entity that separated from the body), or whether it only came into existence at the moment of physical death (and was thus an entity created by the transformation of some physical life-force). In either case, upon physical death the status of the deceased changed from awilu to eṭemmu. Death was therefore a transitionary stage during which humans were transformed from one state of existence to another.

The eṭemmu was not immediately transported to the netherworld after bodily death, but had to undergo an arduous journey in order to reach it. Proper burial and mourning of the corpse was essential for the eṭemmu's transition to the next world. Provided that the necessary funerary rites were performed, the ghost was required to cross a demon-infested steppe, pass over the Khuber River with the assistance of an individual named Silushi/Silulim or Khumut-tabal (the latter meaning “Quick, take [me] there!”), and be admitted through the seven gates of the netherworld city with the permission of the gatekeeper, Bidu (“Open up!”).

Upon arrival in the netherworld, the eṭemmu was “judged” by the court of the Annunaki and assigned a place in its new subterranean community. This judgment and placement was not of an ethical nature and had nothing to do with the deceased's merits during its lifetime. Instead, it had rather a clerical function and confirmed, according to the rules of the netherworld, the etemmu's entrance into its new home.

Yet the judgment and placement of the eṭemmu in the netherworld was not entirely arbitrary or neutral. Just as social hierarchies existed within living communities, so too did a hierarchy between ghosts exist in the “great city” of the dead. The status of an eṭemmu in the netherworld was determined by two factors: the social status of the deceased while alive, and the post-mortem care its body and grave or cult statue received from the living on earth. Kings like Urnamma and Gilgamesh remained rulers and judges of the dead in the netherworld, and priests remained priests. In this respect the social order underground mimicked that above. Some texts such as Gilgamesh and Enkidu and the Netherworld indicate that the deceased's lot in the underworld depended on the number of children one had. The more descendents, the more privileged the eṭemmu's existence in the netherworld, for there were more relatives to ensure the performance of necessary post-mortem rituals.

In the underworld the eṭemmu could be reunited with relatives who had preceded them in death. It should be noted, however, that although the eṭemmu was capable of recognizing and being recognized by the ghosts of people the deceased had known during life, these ghosts do not seem to have retained the deceased's unique personality traits in the netherworld.

In addition to the eṭemmu, living beings were also thought to be composed of a wind-like emanation called in Akkadian the zaqiqu (or ziqiqu). This spirit was sexless, probably birdlike, and was associated with dreaming because it could depart the body while the individual was asleep. Both the eṭemmu and the zaqiqu descended to the netherworld after physical death. Aside from descriptions of dreams, however, the eṭemmu is mentioned far more prominently than the zaqiqu in Mesopotamian literature. This may be due to the fact that, unlike the eṭemmu, the zaqiqu was considered relatively harmless and unable to interfere either positively or negatively in the affairs of the living. It was therefore natural that a greater number of Mesopotamian texts would focus on proper ritual care for the eṭemmu, since these rites were intended to pacify the spirit of the dead so that it would not haunt the living.

The Relationship Between the Dead & the Living

As indicated above, the fate of the eṭemmu after corporeal death depended on performance of the proper post-mortem rituals by the living. First, funerary rites—specifically burial of the corpse and ritual mourning— at the time of death were necessary for the eṭemmu's successful journey to and integration into the netherworld. Second, continued cultic offerings at the deceased's grave or (at least in the pre-Sargonic period) cult statue were required to ensure the eṭemmu's comfortable existence in the netherworld. We have seen that the eṭemmu retained the needs of a living being. Most importantly, it required sustenance. Yet the netherworld was devoid of any palatable nourishment. As the Death of Urnamma articulates, “The food of the netherworld is bitter and the water is brackish” (Cohen 103). The ghost was therefore dependent on the living for subsistence, which was provided through offerings of food and beverage. Absence of offerings reduced the eṭemmu to a beggar's existence in the netherworld. The primary responsibility for performing these offerings fell to the eldest son of the deceased. Scurlock connects post-mortem duties with Mesopotamian property laws by positing that this “is presumably why [the eldest son] also customarily received an extra share of the inheritance” (“Death” 1888).

Both non-elites and elites required such rituals, but the necessity of death cults for the elite was particularly emphasized. The primary difference between death cults for the non-elite and elite appears to have been that, for ordinary people, only the deceased personally known to their descendants –such as immediate family— required individual eṭemmu cults. Distant relatives seem to have “merged together in a sort of corporate ancestor” (Scurlock, “Death” 1889). In contrast, royal cult offerings were made individually to all ancestors of the reigning king.

As long as offerings continued regularly, the eṭemmu remained at peace in the netherworld. Pacified ghosts were friendly and could be induced to aid the living, or at least were prevented from harming them. A person who did not receive proper burial rites or cultic offerings, however, became a restless ghost or vicious demon. Some cases where this could occur included people who were left unburied, suffered a violent death or other unnatural end, or died unmarried. Vicious ghosts pursued, seized, bound, or even physically abused their victims, and could also possess victims by entering into them via their ears. They could also haunt the dreams of the living. Sickness, both physical and psychological, and misfortune were often believed to be caused by the anger of a restless eṭemmu . For example, the suffering servant of the Babylonian poem Ludlul bēl nēmeqi deplores his fate:

Debilitating Disease is let loose upon me:

An Evil Wind has blown [from the] horizon,

Headache has sprung up from the surface of the underworld….

The irresistible [Ghost] left Ekur

[The Lamastu-demon came] down from the mountain. (Lines 50-55, Poem of the Righteous Sufferer)

The Mesopotamians developed many magical means of dealing with vengeful ghosts. Some methods included the tying of magical knots, the manufacturing of amulets, smearing on magical ointments, drinking magical potions, the burial of a surrogate figurine representing the ghost, and the pouring libations while reciting incantations.

Conclusions

In Mesopotamian conceptions of the afterlife, life did not end after physical death but continued in the form of an eṭemmu, a spirit or ghost dwelling in the netherworld. Further, physical death did not sever the relationship between living and deceased but reinforced their bond through a new set of mutual obligations. Just as the well-being of the ghost in the netherworld was contingent upon offerings from the living, so too was the well being of the living contingent upon on the proper propitiation and favor of the dead. To a notable degree, these afterlife beliefs reflected and reinforced the social structure of kinship ties in Mesopotamian communities.