In November 1532 CE, Francisco Pizarro led a group of about 160 conquistadors into the Inca city of Cajamarca. The illiterate and illegitimate son of an Extremaduran nobleman and an impoverished woman, Pizarro had spent his entire life on a quest to become wealthy and be remembered.

After hearing of how a distant cousin of his, Hernan Cortes, had looted millions in gold from the Aztecs, Pizarro was desperate to do the same. He began his career when in 1502 CE, he joined a colonization expedition to the New World. Distinguishing himself in battle, Pizarro quickly rose to second-in-command of the Darien region's army.

He led two unsuccessful expeditions into the western coast of South America, where harsh conditions and native warriors drove his troops back towards the shore. However, fate was to intervene when Pizarro's troops entered the Inca City of Tumbes. The people of the village not only welcomed them, but allowed the conquistadors time to rest and heal.

Quickly the Spaniards became enthralled with not only the large amounts of silver and gold the local chieftains wore, but that the precious metals seemed to be everywhere. Using tactics and subterfuge, they persuaded the chieftains to tell them of a great Inca ruler in the mountains where gold was plentiful.

Taking his new found knowledge and some gold as proof, Pizarro returned to Spain, where he convinced King Charles to not only finance a third expedition, but to make him the governor of all lands he conquered.

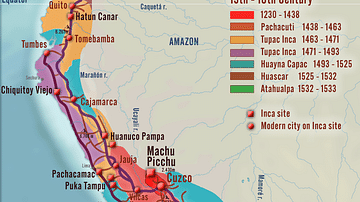

Upon Pizarro's return to Tumbes, he found the once beautiful city destroyed by civil war. Pizarro didn't know it at the time, but his timing could not have been more perfect, as shortly before his arrival Atahualpa Inca had returned from the conquest of defeating his brother Huascar. The battle's outcome had made Atahualpa the “Inca” (only the King could actually use the term Inca.) Upon hearing of the Spaniards arrival, Atahualpa felt he and his 80,000 men had little to fear from the 160 Spaniards. However, as a precaution he sent a few nobles to meet with the Spanish.

The nobles spent two days with the Spaniards, accessing them and their weapons. When he heard their report, Atahualpa sent word that he wished to meet the Spanish at the city of Cajamarca, where he planned to capture them.

When Pizarro entered the mostly deserted city in November, he immediately sent word that he would like to meet with the great Inca ruler at the city's center. As he waited for the Inca's arrival, Pizarro planned a trap of his own. Atahualpa arrived at their meeting point carried in a litter by 80 noblemen and surrounded by 6,000 soldiers. Shortly afterwards, Pizarro ordered the attack. Cannons began to roar with deadly accuracy. The cavalry charged from their strategically hidden positions, and the infantrymen opened fire from long houses. The Inca soldiers and nobles who weren't killed in the first few minutes of the attack fled in fear. Pizarro himself captured Atahualpa Inca.

Fearing for his life, Atahualpa told Pizarro if he would spare him, within two months his people would fill a room 24-feet long by 18-feet wide and a height of 8-feet with gold, and twice that amount with silver. Even Pizarro was taken aback by this amount of wealth and instantly agreed to the ransom.

However during the two months the gold and silver were slowly delivered, the Spanish troops and Pizarro lived with the growing and overwhelming fear that the massive Inca army may be mobilizing to take Atahualpa and kill them.

To prevent this from happening, on August 29, 1533 CE, Pizarro acted as judge, and on the basis of false charges sentenced Atahualpa to burn at the stake. Hearing of his verdict the Inca ruler asked if he could convert to Christianity. He knew if he were a Christian, the Spanish religion would not allow him to be burned to death, and he was right - instead they garroted him.

Upon learning of the Spanish treachery, Inca General Ruminahui hid the approximate 750 tons of gold he was bringing for his king's release in a cave deep in the Llanganatis Mountains. Shortly afterwards Ruminahui was captured, and while tortured to death, he did not reveal the treasure's location.

There the treasure remained for many years until a Spanish man living in the Llanganatis Mountains - Valverde Derrotero - married a certain village priest's daughter. The priest sometime earlier had found the treasure and knowing of the Spanish lust for gold, he showed his new son-in-law its whereabouts. Derrotero had been a poor man, but after the marriage he became a very rich one. Some years later he returned to Spain and upon his deathbed wrote a three-page edict to the king, declaring the treasures location. Known as Valverde's Guide, the piece gave detailed instructions on how to find the treasure.

Immediately the king dispatched a friar named Father Longo to inspect the possibility of hidden treasure. During his expedition Longo sent word that they had found the treasure, but on his way back down the mountains he mysteriously disappeared.

About 100 years after Longo's disappearance, a miner named Atanasio Guzman, who had been mining in the Llanganates Mountains, penned a map, which he said led to the treasure. However, before he could lay stake to his claim he, much like Longo, disappeared in the mountains.

Nothing else was known about the treasure until 1860 CE, when two men —Captain Barth Blake and Lieutenant George Edwin Chapman— believed they had solved the riddle set in search of the treasure. Blake made maps of the area and sent communication back home. In one of his letters he wrote:

It is impossible for me to describe the wealth that now lays in that cave marked on my map, but I could not remove it alone, nor could thousands of men … There are thousands of gold and silver pieces of Inca and pre-Inca handicraft, the most beautiful goldsmith works you are not able to imagine, life-size human figures made out of beaten gold and silver, birds, animals, cornstalks, gold and silver flowers. Pots full of the most incredible jewelry. Golden vases full of emeralds.

However, the men were not to enjoy their spoils, as on their way out of the mountains, Chapman disappeared, and Blake —a career naval officer— somehow fell overboard while transporting some of the gold to be sold.

Is the story true? It's difficult to be certain, but we know a tremendous amount of gold and silver was delivered to the Spaniards. There are the historical accounts of people disappearing, or in Blake's case falling overboard, after announcing they had found the treasure.

There's also the fact that in one of his cryptic clues to the Spanish King, Derrotero mentioned a Black Lake. Sometime in the 1930's CE, the Yanacocha (or Black Lake) gold mine went into operation. To date the mine has produced more than $7 billion US dollars in gold. And, while finding gold in the area Derrotero said the treasure would be doesn't necessarily make the story true, it does make it worth its weight in gold.

This content is provided by

This content is provided by