The Aztec civilization, which flourished in central Mexico between c. 1345 and 1521 CE, was able to provide an astonishingly wide range of agricultural produce thanks to a combination of climatic advantages, diverse artificial irrigation methods, and extensive farming know-how. Their skills at agriculture gave the Aztecs one of the most varied cuisines in the ancient world.

Organization & Methods

In Aztec society, land could be owned by communities (calpolli) and parceled out to individual families for cultivation, or farmers could be resident tenants (mayeque) on large, privately owned estates. Rent was paid in kind to the landowners who were either Aztec nobles (pipiltin), warriors given the land as a reward for services rendered, or the king himself (tlatoani), who all managed their estates through intermediary administrators. On a smaller scale, it was also typical for commoners (macehualtin) to have their own garden plot (calmil), which could supply the family with food. At the bottom of the social strata were slaves (tlacohtin) who, besides working in other industries, were also widely engaged in agriculture.

Two groups of agricultural workers may be distinguished - the general farm labourers who tended the fields, planted, and irrigated crops, and the more specialised horticulturalists who had knowledge of seeding, transplanting, crop rotation, and the best times to plant and harvest. The latter information could be determined from the tonalamatl almanacs, and they not only considered climatic conditions but also auspicious periods and events after which planting and harvesting should take place.

To maximise crop yields, various measures were taken. For example, terracing to increase the area of farmland was widely used, especially from the reign of Netzahualcoyotl. Irrigation was also employed across the Aztec Empire, sometimes in ambitious large-scale projects, such as the diversion of the Cuauhtitlan River to water surrounding fields, but more commonly via artificially flooded fields known as chinampas (see below). Crops were also fertilized using a combination of sludge dredged from the canals constructed wherever Aztecs took up residence and with human excrement, purposely collected from the urban centres.

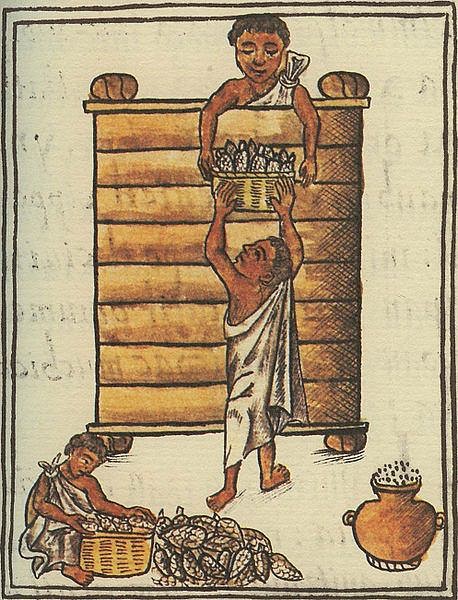

Still, despite these measures, crop yields could be significantly reduced by unfavourable natural events such as excessive rain and even snow or plagues of such pests as locusts and rodents. Accordingly, reserves of grain were accumulated to be redistributed to the destitute in such hard times.

All manner of foodstuffs were cultivated, and non-food crops included cotton and tobacco, which was smoked either in a pipe or rolled into cigars. Once harvested, goods were sold in markets held in the central plaza of all towns. The most famous and largest was the market at Tlatelolco, which each day attracted 25,000 shoppers and as many as 50,000 at the special market held on every fifth day.

Chinampas

Chinampas were artificially raised and flooded fields used for cultivation, and they covered large areas of the Chalco-Xochimilco basin and greatly increased the agricultural capacity of the land. In fact, as many as six crops a year could be grown on the chinampas; no wonder then, that they continue to be used in the present day. Their use in Mesoamerica went back centuries, but it was not until the 13th and 14th centuries CE that they began to spread beyond the lake basin of Chalco-Xochimilco where they eventually covered up to 9,500 hectares (23,000 acres). The chinampas could feed an ever-growing population, which at the capital Tenochtitlan alone was at least 200,000 and perhaps 11,000,000 throughout the empire. Motecuhzoma I, in particular, embarked on an expansion project in the 15th century CE, probably as a direct response to the needs of a rapidly growing population.

Each chinampa field was remarkably similar in size and orientation. Measuring around 30 x 2.5 m, they were pegged out in marshy areas using long stakes. Each plot was bordered with a fence made of intertwined branches which, over time, became more solid as they collected mud and vegetation. The wall was further strengthened by the planting of willow trees at regular intervals. The planting area within the chinampa was filled with sediment and between each plot was a canal which gave access for canoes. The water was provided, and carefully controlled, by a combination of natural springs and artificial constructions such as aqueducts, dikes, dams, canals, reservoirs, and gates. One of the most impressive of these was the 16 km dyke built by Nezahualcoyotl on the edge of Tenochtitlan to block the salty water of Lake Texcoco and create a lagoon supplied by a fresh water spring.

Gardens

The Aztecs also appreciated the cultivation of flower gardens and these were dotted around Tenochtitlan. The most famous example is Motecuhzoma I's exotic botanical garden at Huaxtepec, for which he imported such flowers as the vanilla orchid and cacao trees from the coast, along with specialist gardeners to ensure that they thrived in their new environment. The gardens were irrigated via springs, streams, and artificial canals and featured fountains and artificial lakes. The gardens at Huaxtepec and others such as the ones created by Netzahualcoyotl at Tetzcotzingo were also used to grow foodstuffs and were noted for having plants and trees of medicinal value. In fact, most Aztec upper-class residences had their own pleasure gardens with water features, orchards and herb gardens.

Food & Drink

The Aztec diet was dominated by fruit and vegetables, as domesticated animals were limited to dogs, turkeys (totolin), ducks, and honey bees. Game (especially rabbits, deer and wild pigs), fish, birds, salamanders, algae (used to make cakes), frogs, tadpoles and insects were also a valuable food source. The most common crops were maize (centli, famously used to make tortillas but also tamales and gruel), amaranth (a grain), sage, beans (etl), squash, and chile peppers. Red and green tomatoes were cultivated (but were much smaller than the modern variety), as were white sweet potatoes, jícama (a type of turnip), chayote (vegetable pear), the nopal cactus, and peanuts. The Aztecs also grew many types of fruit including guavas, papayas, custard apples, mamey, zapotes, and chirimoyas. Snacks included popcorn and the sweet baked leaves of the maguey agave.

Not using oils or fats, most dishes were either boiled or grilled, and extra taste was added using condiments, for the Aztecs loved their sauces and seasoning. Examples of these include epazote, toasted avocado leaves, achiote seeds, and, of course, chile peppers either fresh, dried, or smoked. The other two popular flavours for the Aztecs were vanilla and chocolate. The latter came from the beans of cacao pods from the tree which was widely cultivated in extensive orchards near the coast. Beans were fermented, cured, and roasted. Then the beans were ground into powder and mixed with hot water as chocolate was usually consumed as a warm frothy drink. Bitter to taste, it could be flavoured by adding, for example, maize, vanilla, flowers, herbs and honey. So esteemed was chocolate that beans were used as money (even counterfeited) and demanded as tribute from subject tribes. Other popular drinks were octli (pulque to the Spanish), a light alcoholic beer made from the fermented sap of the maguey and pozolli made from fermented maize dough. These alcoholic drinks were, however, consumed in moderation, as being caught drunk could result in all manner of punishments, even the death penalty.