A columbarium is an underground chamber, which the Romans used for preserving the ashes of the dead. During the 1st and 2nd centuries CE, hundreds of columbaria lined the consular highways leading out of Rome, although now only some two dozen are extant. Carefully organised, with neatly stuccoed ceilings, frescoed walls, and mosaic floors, columbaria are not to be confused with catacombs—long rambling underground galleries with crude recesses, which have been gouged out of the living tufa rock and used for inhumation. Since a columbarium represents a self-contained environment, it is ideal for evaluating the funerary rites and commemorative customs of ancient Romans who banded together for a common purpose: the eventual cremation, preservation, and memorialisation of their earthly remains.

The widespread use of columbaria is a phenomenon of the city of Rome, although small columbaria may also be found in Etruria and Campania. Their mass construction seems associated with Augustus' reforms of Rome's archaic burial laws. The closing down of the Esquiline cemetery with its foetid puticuli, or body dumps (and the subsequent reclamation of that land for public gardens), called for a new method of disposal of the dead. Columbaria represent an acceptable economic means of serving the needs of an ever-growing population of slaves and freed slaves.

Columbarium Clubs

Columbaria had various sponsors, such as the emperor, members of the imperial family, or senatorial families. Many, however, were sponsored by independent groups of slaves, former slaves, members of the urban cohorts, and persons who had no apparent connection to each other, who nevertheless pooled their resources to form a funerary association: an example of the last is the no-longer-extant columbarium of the Thirty-Six Associates on the Via Latina. Such groups, which met on a regular basis, acted both as social clubs and as commemorative associations, which ensured that a member who died would receive a proper cremation and disposition of ashes in a designated space.

The cremation itself took place at a nearby ustrina, or funeral pyre (A gigantic ustrina, the size of a football pitch, was located at the 5th milestone of the Via Appia.). If the deceased had enough money, his body would be wrapped in an asbestos shroud so that the cremated bones would not become mixed with the burnt wood from the funeral pyre (The Vatican possesses an example of such a shroud.). After the ashes had cooled, the incinerated bones would be carefully collected and placed in a cinerary urn, which would then be set in its designated niche. The burnt remnants of couch and pyre, however, would be placed in a special terracotta jar and buried under the pavement of the columbarium (The Capitoline Museum possesses such a jar which contained the charred fragments of ivory cupids from a funeral couch).

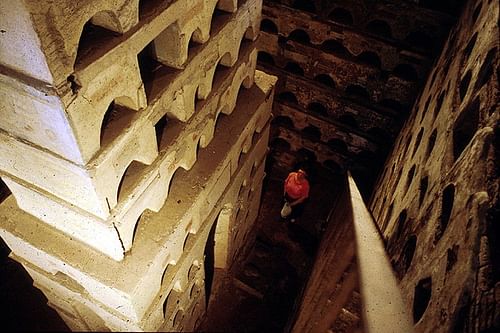

Subscribers essentially reserved and bought space in a columbarium, which they regarded as their respective homes for eternity (The concept of a cinerary urn as a home is evident from many marble ash urns that take the form of houses, carved with tiled roofs, windows, and doors.). Meetings, which combined the business of organization, maintenance, regulation, and even decoration, might be compared to those of present-day condominium associations, which discuss the maintenance of their members' residences. Even structurally, columbaria are analogous to condominiums for the dead, in that row upon row of half-moon niches (loculi)—with jars (ollae) containing ashes embedded unseen into the structure—line their walls like little apartments facing onto a central courtyard.

As funerary institutions, columbaria demonstrate a marked social equality in that their members—mostly of servile origin—elected officers (called decuriones), who presided over the association's meetings. Many columbarium clubs, in fact, were organized like civil governments; in addition to decuriones, they elected "ministers" in charge of specific tasks, such as arranging and paying for the decoration and maintenance of the mosaic floors, wall frescos, staircases, gardens, arbors, sundials, and wells. The better-appointed columbaria even had adjacent kitchens. These funerary clubs, in fact, seem to be rare examples of democratic institutions in an otherwise autocratic Rome, in that associates voted on matters such as membership, regulations, allocation and distribution of ollae, and, notably, the decoration of their future homes for eternity.

Commemorative holidays, such as the Parentalia, the Rosalia, and the Violacia, were central to ancient funeral clubs, whose most important function was to ensure that deceased members were properly memorialised on festival days of the dead. Such occasions brought living members together to decorate the niches with flowers, to light oil lamps, and to pour libations of honey and wine. Libations could be poured directly onto the incinerated bones by lifting the lids of the urns, or, in smaller columbaria where such access was unavailable, by pouring them through clay tubes, which protruded from urns embedded under the floor. In some columbaria, in which loculi are sealed, offerings were instead left in dishes, and oil lamps were burned in commemoration of the departed. On such commemorative occasions, members held banquets in adjacent triclinia, or they celebrated under the trellises of the gardens, which were attached to the chambers that housed the ashes of their deceased members (The fresco of a columbarium at Via Portuense depicts such a picnic, with friends/family playing ball while a boy rides a scooter.). Such celebrations served a double purpose, both for the enjoyment of the living members and for the commemoration of those who had preceded them in death.

Columbaria Size & Shape

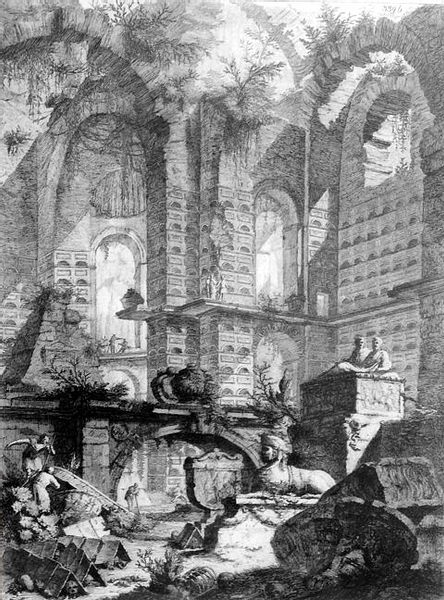

Columbaria were constructed in diverse sizes and shapes. Some were gigantic, such as the now-vanished columbarium of the slaves of Livia (Preserved only in 18th-century engravings, its epitaphs now line the walls of Rome's Capitoline Museum.), and the largely ruined columbarium of the slaves of Augustus. Both contained space for 3000 urns. These gigantic institutions were established for the disposal of the remains of 'families' of imperial slaves and freed slaves. Others, such as the three extant columbaria at the Vigna Codini, which each hold 600-700 ollae, represent slaves and freedmen, some of whom belonged to the imperial family, but an equal number of whom had nothing to do with that august institution—or with each other, to all appearances. The inhabitants of these columbaria, in fact, appear to be companies of strangers.

Many columbaria were relatively small. An example is the hypogeum of Pomponius Hylas, the recorded names of which indicate an assembly of independent associates; its beautifully frescoed chamber contains places for the incinerated remains of approximately 150-300 persons. Many of these small first-century columbaria belonged to individual families and their dependents, or to members of collegia, such as the Organisation of Theatrical Noisemakers (Collegium Scabellorum) or the Organisation of Heralds (Collegium Praeconum). The second century provides examples of even smaller columbaria, which hold only two-to-four loculi, such as the minuscule examples, built haphazardly into a large cemetery, which can be seen today under the Pope's Garage at the Vatican.

Some columbaria indicate evidence of the buying and selling of niches, either for investment or for personal use. An example is the columbarium discovered in 1840 CE in the Vigna Codini, which reveals a vigorous trade in cinerary urns: entire business transactions are recorded in the texts of epitaphs on marble plaques, not only the name of the current owner—the person commemorated—but also those of all previous owners of the ollae. Does such detailed documentation of the names of buyers and sellers reflect some forgotten funerary law? Inscriptional evidence demonstrates that such trade was not limited to this columbarium, which records a dozen such sales by both men and women, including Lucius Pinarius, perhaps a "used olla dealer", who sold at least four loculi in this columbarium. The reselling of cinerary receptacles, whose previous incinerated inhabitants had been discarded, is suggested by inscriptions from other now-vanished columbaria, which advertise ollae virgines, or terracotta urns which have never before been used.

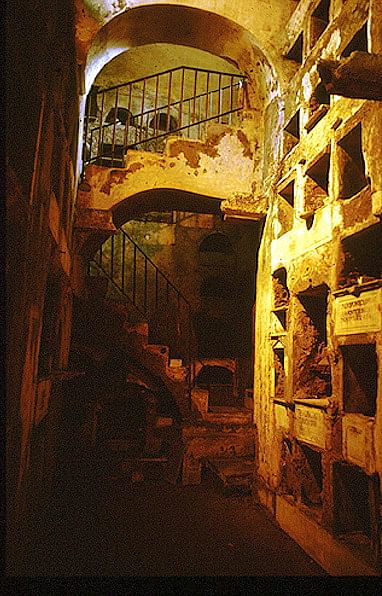

Diversity characterizes the manner in which columbaria were constructed. The very large ones had stairs leading to the upper galleries, the marble corbels of which supported wooden balconies to facilitate viewing and the pouring of libations or lighting of funerary lamps by the relatives or friends of the deceased. The larger columbaria often had square or round central pillars, which served a double function: to support the ceiling and to provide additional space for loculi. Many of these chambers were semi-subterranean and lit by light-wells opening at ground level; long staircases led down into their dim recesses. Still others, such as the columbaria at the park of the Via Latina or the columbarium of the Villa Wolkonsky (the British ambassador's residence), were multi-storied, with a reception or dining hall on the top, and the middle and lower floors reserved for niches and ashes.

ColumbariUM Epitaphs & Inscriptions

At first glance, the epitaphs of columbaria may appear simple, but many display eccentricities, which demonstrate efforts to individualize commemorations in what, because of the magnitude of some of the structures, must have seemed impersonal macrocosms. Not only do epitaphs present data, such as gender, age, social status and profession, but they also designate the right of ownership of adjacent loculi or even entire rows of them, either vertical or horizontal. Other commemorative markers specify who has the right of burial, and they exclude various family-members, slaves or heirs from occupancy, either because they had their own plots elsewhere, or because they had offended the owner, as one sees in an epitaph, which grants everyone the right of burial except for “Secundina, that ungrateful freedwoman.”

Columbarium inscriptions persistently demonstrate the importance of retaining an individual's identity. Although some epitaphs give only the profession and the name both of the deceased and the donor of the loculus, other epitaphs, such as those of the once-elegant marble-lined columbarium discovered in 1852 at the Vigna Codini, demonstrate a preoccupation with social status, even if that status is once or twice removed: one may be a slave—even the slave of a slave, or the slave of an ex-slave—but one nevertheless is a slave of the crème of Roman Society. One sees such an example in an epitaph of the three-year old daughter of the slave of a slave-wardrobe mistress of Agrippina, the mother of the Emperor Nero; the child's father was the slave of Narcissus, the famous Freedman and Secretary of State of the Emperor Claudius.

Other epitaphs proclaim the decedent's special talents or abilities. An example is Tiberius' court jester, Mutus-Argutus, who notes that he made that dour emperor laugh by doing impressions of famous lawyers arguing cases. Efforts to maintain individuality are exhibited in simpler ways, however, such as enlarging the size of lettering of an inscription, so that it will be more noticeable amongst all the other epitaphs in a columbarium.

In the larger columbaria, the fourth row from the bottom—just above eye-level—or the section under the arch of the staircase, seems to have been the preferred position for commemorative purposes according to inscriptional evidence. Some pre-purchased epitaphs even provide specific directions on how to find a particular loculus, although in one columbarium, the problem of easy access seems to have been solved by someone's scratching a large “X” into the stuccoed wall to mark the spot of a designated niche. Such contrivances demonstrate the efforts made by individuals to distinguish themselves in what—despite efforts to rationalize the fact with poetic sentiments or adornments imitating domesticity—remained, in effect, vast warehouses for the dead.

Columbarium Frescoes & Stuccoes

Unlike an outdoor cemetery, which is designed so that the passerby will stop to read an epitaph, a columbarium was essentially a private place not intended for casual viewing. Only fellow-club members, who may or may not have been relatives or friends, would see these epitaphs, and then only dimly, by flickering oil-lamplight. For all their seclusion, however, Roman columbaria exhibit a rich diversity of design and decoration, as if they were meant to be enjoyed by all: finely executed frescoes—joyous renderings of birds, rabbits, musical instruments, Nile pygmies, beasts, and dancing puppet-like figures, such as those of the Columbarium of Scribonius Menophilus, seem to be the rule rather than the exception. That columbarium, discovered in 1983 CE on the grounds of the Villa Doria Pamphili, furthermore, provides a measure of confidence for the accuracy of the testimony of a 17th century CE eye-witness of a now-vanished nearby columbarium from the Via Aurelia (Such evidence must always be viewed with a degree of caution.). Pietro Santo Bartoli, observer, antiquarian and engraver, depicts a mosaic columbarium floor, on which scantily clad men with conical hats are dancing, holding noisemakers. They are similar in attribute to those cavorting on the walls of the nearby columbarium of Menophilus, which Bartoli could not possibly have seen since it remained buried, from the first century CE until the late 20th century CE.

The pictorial range and iconography of the frescoes and stuccoes of Roman columbaria, which maintain the fiction of a domestic environment, imitate the themes found on wall paintings of houses of the Augustan era. Not only do they represent animals, birds and dancers, but they also depict sacral-idyllic landscapes, theatrical masks, and performances of comedies and tragedies. With similar subjects displayed on marble urns, some of which themselves are carved like houses, such depictions are further indications of the ancient concept of columbaria as mansions for the dead.

Plunder, Destruction, & Transformation of Columbaria

A study of columbaria is also an inquiry into the history of both the plunder of ancient monuments and the ongoing battle between archaeology and urban progress during the 19th and early 20th centuries CE. For although numerous columbaria have come to light in the environs of Rome since the 15th century CE, the majority have been demolished indiscriminately almost as soon as they had been discovered. The artist Piranesi provides evidence of the systematic stripping of the edifices in his 18th century CE engravings. The next two centuries continued and almost completed their relentless dismantling. Archaeologists, recording specifics, were in a constant race to gather information before construction crews poured cement foundations during Rome's extensive building projects of the 19th century CE. Perhaps the most insidious wreckers of the majority of those columbaria that have managed to survive, though, are time and neglect.

A few edifices have endured a kinder fate: among them, the three gigantic columbaria of the Vigna Codini, the intimate hypogeum of Pomponius Hylas, and the semi-ruined columbarium of the tomb of the Scipios—all between the Via Latina and Via Appia—and those of the Doria Pamphili on the Gianicolo, including that of Scribonius Menophilus, in its remarkable state of preservation; and the unusual conglomeration of second-century columbaria under the Vatican's private parking lot.

Still others have undergone bizarre metamorphoses: the columbarium of the slave family of Augustus on the Appian Way, which had been transformed into a wine shop when Piranesi saw it, now exists as a charming restaurant, where one may dine among the dead (Considering their custom of Columbarium banquets, the dead would likely have approved unreservedly.). A clutch of columbaria on the Via Portuense has now become a central feature of the Museum Drugstore. With its supermarket, bar, disco, and used-car dealership—all clustered around 2nd-century CE columbaria, which are clean, well-lit and meticulously displayed—the Museum Drugstore may seem wacky, but it is actually an enlightened experiment by Professor Fiorenzo Catalli of the Soprintendenza Archeologica di Roma in the preservation of ancient monuments—the idea being to build around, not on top of archaeological remains.

Relatively few columbarium epitaphs remain in situ. Evidence for them, however, survives in 17th-18th-century CE engravings, such as those of Bartoli and Piranesi; in 19th-20th-century CE excavation reports, and in the thousands of inscriptions recorded in volume VI.2 of the Corpus of Latin Inscriptions. Scrutinising this wealth of evidence grants us a tantalising glimpse into the lives and deaths of the "nobodies" of the Julio-Claudian era, whose names and existence are unknown to the historian Tacitus or the biographer Suetonius. Through their epitaphs, however, these occupants of Rome's columbaria—men, women, and children who were omnipresent but invisible at the heart of the Roman Empire—materialise for us momentarily as eternal dwellers in Death's Mansions.