In the early days of the Achaemenid Empire (c. 550-330 BCE), the kings came to realise that, if they were to be able to administer the vast mass of land and the multicultural people who inhabited it, they had to create an organizational system that would enable administration without causing any rebellion or disorder and, more importantly, ensure the timely and fair payment of tribute to the court.

One of the major achievements of the Achaemenid rulers was their ability to recognise and utilise the already well-established practices of the conquered lands as well as those systems of government which had come before them; thus the centralised organised mass bureaucracy of the Achaemenid Empire was based on the previously existing Akkadian, Assyrian and possibly Median administration systems as well as the Egyptian government.

Under the reign of Cyrus the Great (r. c. 550-530 BCE) and Cambyses II (r. 530-522 BCE), the conquered areas of Elam, Media, Lydia, Babylonia, Egypt, and several eastern Iranian tribes were more or less in a form of a loose federation of autonomous entities. When it came to tribute, they were subjected to irregular taxation if any at all. The king relied heavily on the non-Persian officials present in the already established form for governments in these subject states. These forms for organization, or lack of it, led to clashes between the Iranian noblemen and also to “nationalism” in the conquered areas, which finally resulted in chaos and rebellion after Cambyses' death.

Darius Organises His Empire

When Darius I (r. 522-486 BCE) ascended the Achaemenid throne, he had a major task ahead of him. He not only had to reconquer the rebellious areas but also needed to integrate them into a systematic empire. Knowing that the three main issues that had to be under control for his empire to work were a “sound military, stable economy and a legal system”, he set out to organise the empire with these aspects in mind.

The system of division, which Darius used, can be observed on his tomb in the form of a relief situated on the top part of the rock carving. Here he is portrayed on his throne, which is “supported by 30 figures of equal status”; this symbolized the subject people of the empire. The countries other than Persia or Persis are listed in what seems to be geographical order.

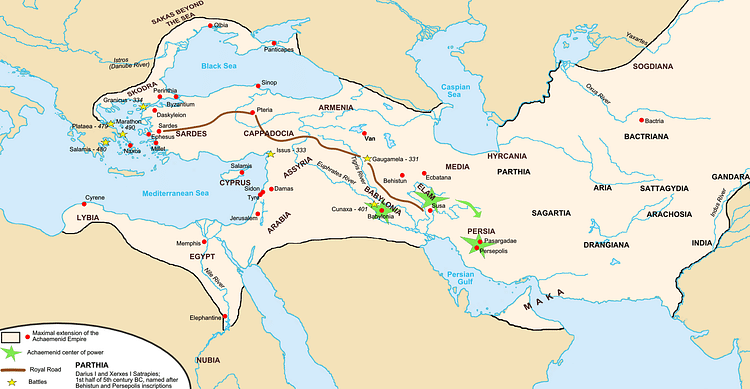

Herodotus (3.89) mentions that “Darius joined together in one province the nations that were neighbours, but sometimes he passed over the nearer tribes and gave their places to more remote ones.” Dr. Shahbazi applies this system to the recorded lands in the mentioned relief and distinguishes between the Persian homeland six other nations. This “seven folded” partition of the empire, which seems to recall the traditional Iranian division of the world into seven regions, illustrates the division of the empire as follows:

- the central region, Persis

- the western region encompassing Media and Elam

- the Iranian plateau encompassing Parthia, Aria, Bactria, Sogdiana, Chorasmia and Drangiana

- the borderlands: Arachosia, Sattagydia, Gandara, Sind and Eastern Scythia.

- the western lowlands: Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia and Egypt.

- the northwestern region: encompassing Armenia, Cappadocia, Lydia, Overseas Scythians, Skudra and Petasos-Wearing Greeks.

- the southern coastal regions: Libya, Ethiopia, Maka and Caria.

Within these regions, Darius established 20 provinces, called satrapies (following the model of the Assyrian Empire). Each one had a governor, or satrap, who was directly responsible to the king, and each satrapy had a fixed annual tribute. Herodotus provides us with a detailed list of the satrapies from west to east starting with Ionia, and names their annual tribute paid to the court, as well.

As noted above, the Assyrian administration system seems to have been one of the more important models for the Achaemenid bureaucracy. The Assyrian administration system was reformed extensively by Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (745-727 BCE). Since he had been a provincial governor prior to the coup which made him king, he understood the importance of limiting these administrator's powers. He enacted legislation which divided the satrapies and halved the governor's power so that the provincial governors could not do as he did and rebel against him. By creating officials who were directly under his control, and who supported the local rulers, he was able to hold the local ruler in check. He also started an “intelligence system”, which transmitted reports by using state stage-posts, making sure that the “civil servant” remained loyal and efficient.

These Assyrian reforms can be observed in the Achaemenid administration as well. Most of the satraps appointed by Darius were Persian noblemen, who were to administer the tax districts within the satrapies, and each one of these districts could again be subdivided into “sub-satrapies” and again into smaller entities. These had their own governors who had either been appointed by the central court or by the satrap himself.

The Trusted Men & Government Officials

To be able to ensure a fair evaluation of each satrapy, the king would send a committee of “trusted men” to assess the income and spending of each district in each satrapy. Babylonian documents from that period show the existence of detailed land registries with property boundaries, ownership and land assessments. Further, the Elamite texts found in Persepolis mention officials who “write people down” and “make enquiries”. In essence, a central peoples' registry was created in each satrapy and was used to assess taxes and probably also to register able-bodied men for the army levies. The policy of "trusted men" who were sent by the ruler to observe and report on activities in the provinces was borrowed from another earlier system: that of the Akkadian Empire (2334-2083 BCE). Sargon of Akkad (2334-2279 BCE), the founder of the empire, instituted this exact system in order to maintain order and prevent rebellion.

The Persian government borrowed another policy from Akkad. To avoid concentration of power in one person alone, each satrap had a Royal Secretary, whose job was to observe the affairs of the state and also to communicate with the king. A Royal Treasurer also worked with the satrap, safeguarding the provincial profits. Finally, the Garrison Commander was in charge of the military units stationed in the satrapy and was only responsible to the king. Additional inspections were carried out by “Royal Inspectors” who acted as the king's eyes and ears; they had full authority over the satrapy's affairs and answered only to the king.

It seems that the coordination of the imperial administration was the responsibility of the chancery whose headquarters were at Persepolis, Susa, and Babylon. Thus the main cities of the empire, such as Bactria, Ecbatana, Sardis, Dascylium, and Memphis, also must have had their own divisions. It is important to mention that bureaucratic organization was deeply rooted in the Middle East and was also used by Cyrus and Cambyses in the earlier days of the empire; however, Darius reformed it in accordance with the needs of a centralized empire and the subject states.

Money & Trade

Darius also introduced a new monetary system which consisted of silver coins weighing 8 g and gold coins weighing 5.4 g, which corresponded to 20 silver coins. The gold coins were called “Dareiko” or darics. However, it is important to mention that most of the subject nations minted their own coins and used their own monetary systems side by side with the new system introduced by Darius.

The new modified administration also helped to enhance trade and offer safe trade routes to the subject people by building new roads and improving the road networks. New way stations were built throughout the empire, offering travel safety, and entitled authorized travellers to draw provisions and mounts. He also sponsored the buildings of canals and underground waterways. The imperial navy kept the seas and the coasts of the empire safe and free from pirates, thus encouraging free trade between the satrapies.

Conclusion

The early Achaemenid kings, who shaped the Achaemenid Empire and its doctrines, based a number of their practices and administration on earlier bureaucratic systems. Where they really differed from the earlier empires was in their tolerance of, and respect for, the conquered people and their cultural practices and beliefs.

All freeborn inhabitants of the Achaemenid empire were considered subjects of the Persian king. Nevertheless, in some constituent elements of the empire quite different forms of political organization prevailed (e.g. monarchic, oligarchic, aristocratic, democratic, and theocratic), and the rulers enjoyed autonomy in internal affairs. (Dandamayev, M., 631-632)

This was the Achaemenid breakthrough: clearly understanding what was possible and doable with a pre-existing practice or system and understanding what actions were necessary to run the empire efficiently while maintaining the Achaemenid doctrine of tolerance and respect.

This content is provided by

This content is provided by